By Julie Shapiro

Eric Greenleaf’s journey to the front lines of Lower Manhattan’s school overcrowding crisis began when he looked out his window.

Greenleaf and his family live in an apartment facing the construction of the new K-8 Beekman St. school. He and other parents were counting on the school to open in fall 2009, to relieve the overcrowding at P.S. 234. But last year, from his window, Greenleaf watched work on the school’s foundation grind to a halt. Developer Bruce Ratner couldn’t get financing for the 76-story apartment tower, which would house the school in its base.

“It became pretty obvious that the school was probably not going to open on time,” Greenleaf said last week.

As months passed and the site stayed dormant, Greenleaf decided to take action: He started an overcrowding committee at Tribeca’s P.S. 234, where his twin son and daughter were in first grade.

At the end of last March, Ratner restarted work on the Beekman tower but pushed the school’s opening date to 2010, and some think with tower construction, it won’t be safe to open the school until 2011. With Beekman delayed and the green school in Battery Park City not opening until 2010, Greenleaf and others realized that Lower Manhattan children would need temporary school seats in 2008 and 2009.

He and a core group of P.T.A. members mobilized parents at P.S. 234 and P.S. 89. They met with elected officials, rallied at City Hall and sent thousands of postcards to the mayor and chancellor. Greenleaf used his statistics background — he is a professor of marketing at N.Y.U.’s Stern School of Business — to show that Downtown’s booming population will translate into record numbers of kindergarteners flooding local schools.

The parents have won their first battle: Starting this fall, P.S. 234 is borrowing two classrooms in Manhattan Youth’s new Downtown Community Center. P.S. 234 had to close its art and science rooms this year to make room for the large kindergarten class, but the Manhattan Youth rooms will restore that space.

“I don’t think it would have happened without the parental activism we had,” Greenleaf said.

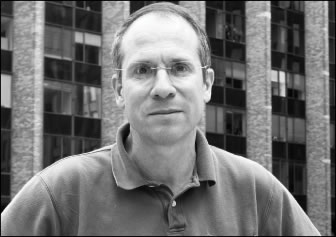

While Greenleaf, 52, is quick to acknowledge the efforts of other parents Downtown and across District 2, he has become the parent leader of the anti-overcrowding campaign in Lower Manhattan. “It’s like having another job,” he said of the hours he has put in. Since he started the Overcrowding Committee, parents sometimes recognize him around Lower Manhattan.

Activism runs in Greenleaf’s family. His aunt, Mona Levine, fought for more parental control back in the 1960s when her two children attended P.S. 1 in Chinatown.

Greenleaf later got his first protesting experience as a high school student in Durham, N.H., a college town. It was 1970, the year Nixon invaded Cambodia, the year of the Kent State shootings.

Greenleaf and his classmates published an underground newspaper called “Free” (the name reflected the price). This was before word-processing, so Greenleaf and the other students painstakingly typed their stories, then hitchhiked down to Boston, where they found a printer to run off copies at a cheaper rate. The paper was filled with stories about the Vietnam War and other national and international issues.

What finally got the paper’s staff in trouble, though, was a topic closer to home: birth control. They published a story about the different types of birth control — a relevant topic, they felt, because several girls at their high school were pregnant. Parents were furious and demanded that the paper be discontinued, but Greenleaf and his fellow students eventually got it reinstated after a meeting with the school board.

Compared to the murkiness of Vietnam, today’s school overcrowding issue is clear, Greenleaf said.

“It was obvious it was happening, and it was obvious why it was happening,” he said. “The population was growing at a faster rate than schools were being built. Everyone agreed the city hadn’t planned properly.”

Greenleaf said he was surprised to find out that the D.O.E. did not have full-time demographers tracking population growth trends.

“I was shocked to find out how little planning they do,” Greenleaf said. The city was unable to handle Downtown’s rapid population changes, based partly on parents deciding to raise their kids in the city, not the suburbs, Greenleaf said.

Will Havemann, spokesperson for the D.O.E., said the department hires two consulting firms to create a yearly report on demographics.

As kids return to school this week across the city, Greenleaf said P.S. 234’s Overcrowding Committee is looking ahead to next fall, when both P.S. 234 and P.S. 89 face an even bigger overcrowding problem. Greenleaf is pushing for new classrooms in the Cove Club condo building in Battery Park City, but the D.O.E. wants to use converted office space in 26 Broadway instead. Another solution would be to build temporary classrooms, Greenleaf said.

Greenleaf also expects the P.T.A. to work on school district rezoning this year. The city will soon redraw the elementary school lines to fill the new Beekman and Battery Park City schools.

Finally, Greenleaf hopes parents will weigh in on an issue that might be too political for the P.T.A.’s: mayoral control of schools, which is up for renewal next year. Greenleaf thinks the city needs to be more responsive to parents’ needs, and mayoral control should only be renewed in an altered form.

Greenleaf’s 6-year-old twins, Anna and Leo, started second grade this week at P.S. 234. They don’t entirely understand the work their father does on their behalf (Greenleaf tells them about “the committee that Daddy’s on”). But regardless of the impact of overcrowding on his children, Greenleaf said quality education is worth fighting for.

“Other than making sure kids are well fed and have a roof over their head, what could be more important than making sure they get a good education?” Greenleaf said. “If schools suffer, Downtown suffers.”

Julie@DowntownExpress.com