BY JACKSON CHEN | Having mounted five flights of stairs, you fumble for the keys to your apartment. But before you’re able to enter your personal sanctuary, a legal notice with the jarring bold words “NOTICE OF EVICTION” is what welcomes you home.

You’re instantly shaken out of your after-work mellow and dropped into a place of panic. With no idea what to do next, you’re left only with the fear you’ll be kicked out of your home in the next few days.

You’re not alone. Tenants throughout the city, especially but not exclusively those of low income, find themselves in Housing Court, fighting over eviction notices, disputes about unpaid rents, and landlord-initiated disruptions. In 2016 to date, more than 60,000 Housing Court judgments have been rendered, according to the New York City Housing Court’s statistics.

The eviction notice may or may not clue you in to the next steps required. Once you figure out that you need to head to Housing Court — at either 111 Centre Street downtown or 170 East 121st Street in Harlem — you’ll find yourself in an arena where landlords and their legal representatives have the home court advantage, according to Manhattan tenants who have gone through the process.

Those with business in the Centre Street Housing Court are directed to Room 225, which has a hanging sign “landlords and tenants.” The faces of tenants inside carry looks ranging from distress to weariness, while the attorneys who trickle in greet the court staff behind the counter with familiarity, warmth, even enthusiasm.

The Housing Court is about as welcoming as a supermarket’s self-checkout aisle, where you have a vague understanding of where to go but no clear idea of how it all works. The clues can be found in a slow-progressing TV slideshow or among the plethora of fliers in the “Forms and Information” section. It’s not uncommon to see families whose native language is not English struggling to figure out the documents before them. Those dressed for work mix in with elderly people, some of them with walkers or canes. The longest line is for “Self Represented Answers.”

When you’ve figured out what information you need to present to court staffers, you’ll receive a slip and be told to wait your turn on a bench. When your name is finally called, you are either summoned into the courtroom or informed of the day you must report back to the court. When you do make it into the courtroom, you may feel anxious and alone — and will likely face an attorney representing your landlord who enjoys a rapport with court staffers. As a layperson, you must decipher the legal language being used as you try to explain your case to the judge and defend yourself and your right to a home. Your opponent is a lawyer well versed in the city’s housing laws.

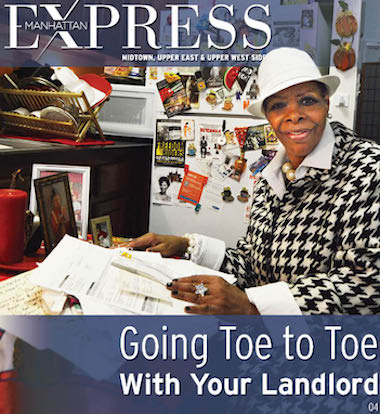

“I was scared shitless,” said West Harlem resident Rochelle Thompson of her first appearance in Housing Court. A professional vocalist and the self-styled First Lady of Jazz, Thompson has found herself there for cases every year since 2011. In the worst instance, Thompson said, her landlord attempted to evict her for an outstanding balance of $7. She was able to satisfy the judge by presenting a clipped stack of paid rent receipts and bank statements.

In her first time before a housing judge, Thompson recalled, she felt an emotional burden that crashed over her like a violent wave.

“I would be in the hallway alone crying, and I could not understand why I was crying,” she said. “I realized later it was an involuntary response because I knew I shouldn’t be down here.”

Thompson said she’s faced accusations of unpaid rent, money owed in late fees for those unpaid rents, and breaking the terms of her lease. As she thumbed through the stacks of documentation she keeps to protect her home, she paused at the photos of an eviction attempt where black garbage bags filled with her belongings and furniture were plopped right outside her apartment.

“They sent a building manager up to my apartment,” Thompson said. “I saw them taking my things out of my apartment.”

After a few phone calls and yet again proving no wrongdoing on her part, she told the landlord’s crew to “bring my motherfucking shit right back up here.”

After that experience, Thompson began studying housing law and now feels capable of defending herself in court. She even offers advice to others who find themselves equally lost when they first face a battle against their landlord’s attorneys.

When Sandra Johnson, an East Harlem resident, faced eviction, she was able to turn to Thompson for guidance through what was a hairy ordeal.

Along with the rest of the tenants in her five-story walkup, Johnson was threatened with eviction when her landlord served notice that the building would no longer be rent-regulated within two years. In Housing Court, she found herself having to prove to judges repeatedly that her building is, in fact, rent-regulated under the the state Division of Housing and Community Renewal.

In a cascade of eviction attempts, Johnson has been accused of being a hoarder, of being a nuisance to other tenants, and of owing money to the landlord.

Johnson is no longer a stranger to Housing Court and expects to visit again next week, this time to bring harassment charges against her landlord for the poor living conditions he is imposing on her. One of the building’s few remaining tenants, Johnson said the situation has taken a toll on her and her family, but she is committed to continuing the struggle.

“I’m getting tired of fighting,” she said, her voice cracking with exasperation. “They’re wearing me down.”

Johnson said her children’s educations have been compromised because of her need to appear in Housing Court. She recalled hectic days where she had her kids with her in Housing Court, and then rushed them to school, before returning to court and later picking them back up when school was out.

“I’m fighting for my home, for my kids, and it felt like nobody cared that I was alone,” Johnson said of her experiences in Housing Court. “I felt like a mother that was crippled, like they cut my legs beneath me.”

She once hired a lawyer, but was told she didn’t have a case and was out $250. Eventually, she decided the best option was to represent herself, much as Thompson did. The two women’s experiences have been much the same.

“I felt like this court was a kangaroo court, that all the lawyers were being justified by the judge,” Johnson said. “It felt like New York didn’t have honest people anymore, not lawyers, not judges. It was like I was living in a nightmare.”

The nuisances she endued from her landlord, she said, didn’t stop with having to spend time in court to defend her home. The building conditions she faces when she returns to that home, she worries, could damage her children and grandchildren’s health.

There’s a noticeable sag in portions of the floor as Johnson walks across her apartment. As she shakes the radiator, which she complained often doesn’t provide heat, there is also give there. And glue traps line the edge of her kitchen to guard against the rats, ants, and termites her family lives amidst. Heaps of clothes and housewares are stacked arbitrarily in her hallways and bedrooms because her landlord never completed the promised closets and cabinets.

Johnson has complained numerous times about building renovations outside her apartment she suspects are being carried out illegally. In a back staircase exit from her apartment — access to which has been sealed off in all of the building’s other units — Johnson points to a break in the wall, behind which a new stairwell has been constructed. Her stairway exit leads to a neglected backyard filled with dime bags, refuse, and dead birds.

Susan Schwartz, a member of Community Board 7’s Housing Committee, is also butting heads with a landlord seemingly hostile to her presence in his building. The Upper West Side high-rise, she said, has undergone illegal renovations in recent years. She is convinced that that the noisy and dusty construction projects, undertaken without valid permits, are part of an effort to force rent-stabilized tenants out.

“In our building, there are 303 units in a 20-story building,” Schwartz said. “Less than half of them are still rent-stabilized. When I moved in, they were all rent-stabilized.”

Over the past five years, she said, 75 apartments in her building have undergone massive renovations that disturb the neighboring tenants. And the harassment does not stop at the doorway to those units. Hallway and façade work involving jackhammers and the spread of dust throughout the building has also been a fact of life in the building, according to Schwartz. The only construction mitigation effort she’s seen has been the use of plastic door coverings slapped up with blue painter’s tape.

She and her neighbors finally formed a tenants association to pursue their legal rights.

“We’re paying rent and yet we feel like we’re living in a construction zone,” Schwartz said. “It’s not a construction zone, it’s our homes.”

Shortly after the association formed, Schwartz said, the trash rooms located on each floor were replaced by a central basement garbage receptacle where tenants must lug their garbage via the building’s passenger elevators.

Upper West Side City Councilmember Mark Levine and his Bronx colleague Vanessa Gibson have heard similar horror stories from tenants over and over again. For the past two years, they have worked to advance Intro 214-A, which would provide free legal counsel to low-income families facing Housing Court disputes.

“There is no fairness in any court when only one side has an attorney,” Levine said. “But that is the reality today for tens of thousands of tenants who face the threat of an eviction.”

On September 26, the Council’s Committee on Courts and Legal Services held a roughly six-hour public hearing on Intro 214-A.

“Too many families face unscrupulous landlords, they face harassment by their landlords, and they are simply pushed and priced out,” Gibson said. “We recognize that legal representation is about fairness and equity. It is about balancing the scales of justice in Housing Court.”

Those testifying at the hearing ranged from legal experts, who explained how proceedings in Housing Court are tipped in favor of landlords, to an 11-year-old girl who represented her Spanish-speaking parents. Dozens of tenants said they often go without gas, heat, or hot water — at times in retaliation for their challenging landlords in Housing Court.

Edward Josephson, the director of litigation at Legal Services NYC, has defended tenants in Housing Court for nearly 30 years.

“When experienced counsel is provided for tenants, the chance of being evicted is dramatically reduced,” he said. “And even if they have to move, they can move with dignity and not be forced to stay in a shelter in the meantime.”

In Josephson’s view, Housing Court is “completely incapable of dispensing even rudimentary justice to low-income families.”

Access to adequate representation is sorely lacking, he said.

“How do you tell a single mom, disabled person, or senior citizen the person next to her on the bench is going to get a lawyer and she is not?” Josephson said. “The one thing I hate about my job is having to say that over so many years. I am looking forward to the day I and my colleagues will never have to say that again.”

Given the economic pressures in today’s housing market, however, even access to legal counsel may not be sufficient to protect Manhattan apartment dwellers, a point underscored by Carmen Vega-Rivera, a tenant’s advocate who is a leader at the nonprofit Community Action for Safe Apartments.

“It’s a mosaic of people, it doesn’t matter your race, your income, where you’re from, what your education is,” she said in describing the daily scene at Housing Court. “When a landlord wants you out and he wants to harass you because he wants to displace you, everybody is being pushed out.”