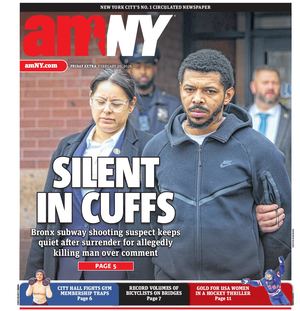

New York City health officials on Friday declared the end of a Legionnaires’ disease outbreak in Central Harlem that sickened more than 114 people and left seven dead.

Acting Health Commissioner Dr. Michelle Morse said no new cases have been reported since Aug. 9 during a virtual press briefing on Aug. 29, while announcing a package of proposed reforms aimed at reducing the risk of future outbreaks, including more frequent testing of cooling towers.

Of the 114 people who were infected, 90 were hospitalized, and six remain in the hospital. The seventh death linked to the outbreak was announced by the DOH on Thursday.

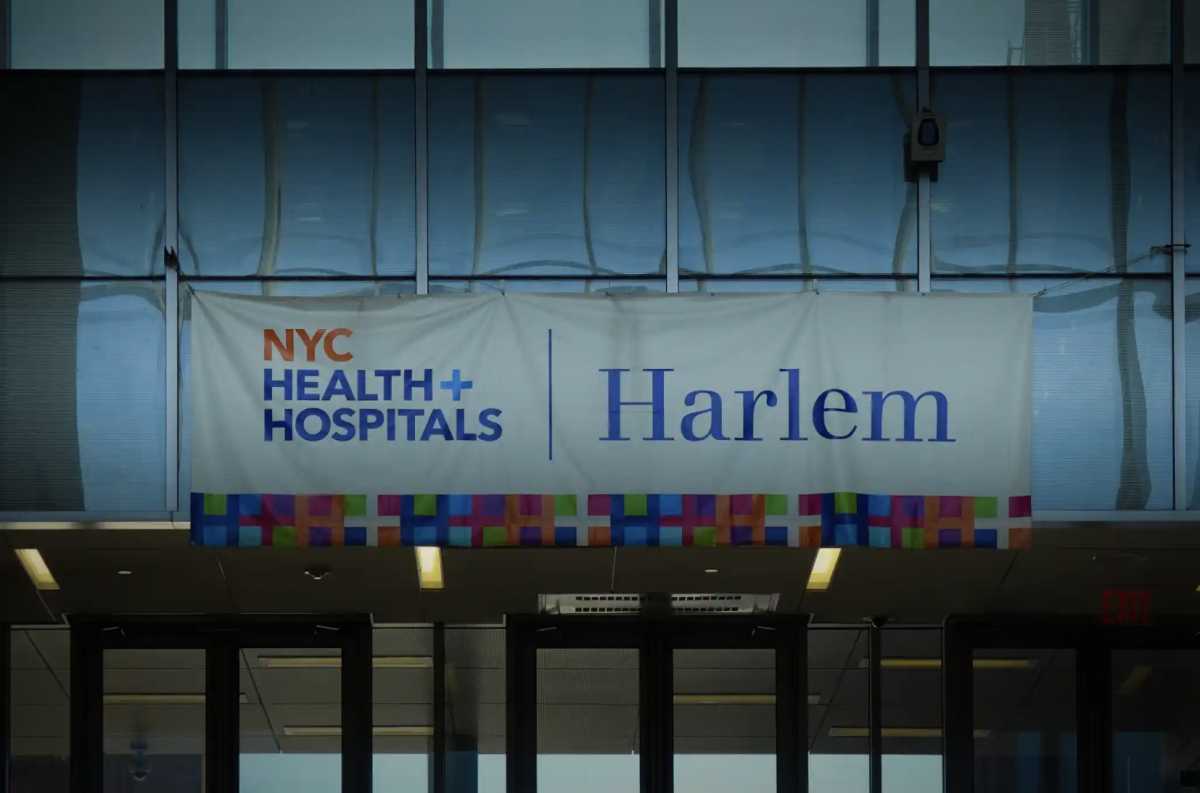

After extensive testing and genetic analysis, health investigators traced the bacterial strain to the cooling towers at Harlem Hospital and a nearby construction site on West 137th Street, where the city’s new Public Health Lab is under construction, overseen by Skanska USA under contract with the city’s Economic Development Corporation.

Inspectors had set out ot investigate the source of the outbreak from the 12 water-cooling towers across ten buildings in the area, which had tested positive for the Legionella bacteria that causes the pneumonia-like disease in recent weeks.

Morse said both sites, which are currently at the center of negligence lawsuits filed by two Long Island construction workers, have since disinfected and sanitized their towers and are working with the DOH on long-term safety measures.

“New York City has among the most rigorous and protective legislation on cooling towers in the nation. But the reality is that when you try to control nature, it is very difficult work; even still, moments like this demonstrate our system can always be improved, and I intend to do just that,” Dr. Morse said.

Proposed changes to the city’s testing mechanisms include requiring cooling tower testing every 30 days instead of every 90, increasing fines for noncompliance, hiring more inspectors and engineers, expanding proactive sampling capacity, and creating neighborhood health teams to provide information during emergencies. The Health Department will also review its existing rules to strengthen prevention efforts.

First Deputy Mayor Randy Mastro said the outbreak underscored the need to act quickly. “It is never good enough just to remediate after the fact,” he said, adding that the city will move forward with new regulations “to ensure this doesn’t happen again.”

Reporters pressed officials on staffing shortages that limited routine inspections, after Gothamist reported that the city’s Department of Health lost more than a third of its cooling tower inspectors over the last three years.

Deputy Mayor Randy Mastro and Dr. Morse responded that reforms are needed regardless of staffing history, stating that the city will hire more inspectors, but specifics on numbers and budget were not disclosed.

“We are committed to expanding the resources of the department,” Mastro told reporters. “This is not a call cost issue. It’s an issue of providing the resources and making the reforms that, from this experience, we deem necessary and appropriate.”

“Dr Morse and the health department will make recommendations on how many more positions they want for both testing and inspections, and enforcement, and City Hall will be promptly responsive to those requests, I’m sure,” he added.

Deputy Commissioner for Environmental Health Corinne Schiff acknowledged that the Health Department had been unable to inspect all of the city’s roughly 5,000 cooling towers annually due to staffing, but stressed that during the Harlem outbreak, inspectors sampled every tower in the investigation zone within 72 hours of the first cases being detected.

Dr. Morse responded that even when buildings follow city regulations, Legionella bacteria can still be found, since compliance does not completely eliminate risk.

Officials also addressed concerns about Harlem Hospital. Dr. Mitchell Katz, President of NYC Health and Hospitals, said they conducted their own weekly testing of the hospital’s cooling tower as a precaution, separate from city inspections. He said the tower was disinfected on July 2, three weeks before the first case in the Harlem cluster was reported.

Katz explained that different tests yield different timelines: preliminary PCR tests are done weekly, while culture tests, which take about two weeks, provide more definitive results and allow for bacterial fingerprinting. He said the city Department of Health tested the tower on July 25 as part of the outbreak investigation, with the initial PCR test showing negative results. Culture results confirming the presence of Legionella came approximately two weeks later, followed by fingerprinting to match the strain, while the tower was remediated on Aug. 2.

“This is just to emphasize why I support more frequent testing and also a certain amount of humility about nature and ubiquitous organisms that like standing water in warm weather, and the limitations of the cooling towers are cooling the air we breathe, and so you can, you cannot over-chemicalize that air,” he said.

On Friday, mayoral candidate former Governor Andrew Cuomo renewed his call on the State Department of Health to open an independent review of how the city acted before and during the Harlem Legionnaires’ disease outbreak. He said that the city’s dual role as regulator and landlord of the affected buildings creates an “inherent conflict.”.

“New Yorkers deserve complete confidence that the regulations designed to protect their health are being followed—whether by private landlords or City government itself,” Cuomo said. “With the source of this outbreak now tied to a city-run facility, it is all the more important that an independent review be undertaken to ensure accountability, transparency, and public trust.”

In addition to the recent Harlem cluster, health officials are now investigating separate Legionnaires’ cases at two Bronx buildings, Parkchester North and South, triggered by the identification of two cases in each over the past year.

Dr. Morse said the building owners are complying with the investigation and that neither probe is linked to the other but rather to the individual buildings’ hot water systems.

“We do not have any additional updates at this time about those investigations, but I do want to emphasize that those investigations are completely separate from the central Harlem cluster,” said Morse, adding, “Again, it is the summer time. This is a time when Legionella bacteria, which are again quite common in the environment, tend to thrive.”