BY JOHN BAYLES | One of the most common catch phrases among educators today is “global community.” Schools, whether private or public, are aiming to offer their students the best avenues to allow them to become global citizens and to receive an education that ensures success in any profession, anywhere in the world.

A Lower Manhattan school is taking the idea of a global education quite literally, giving its students not only the chance to learn about other countries but to participate in an actual “global classroom.”

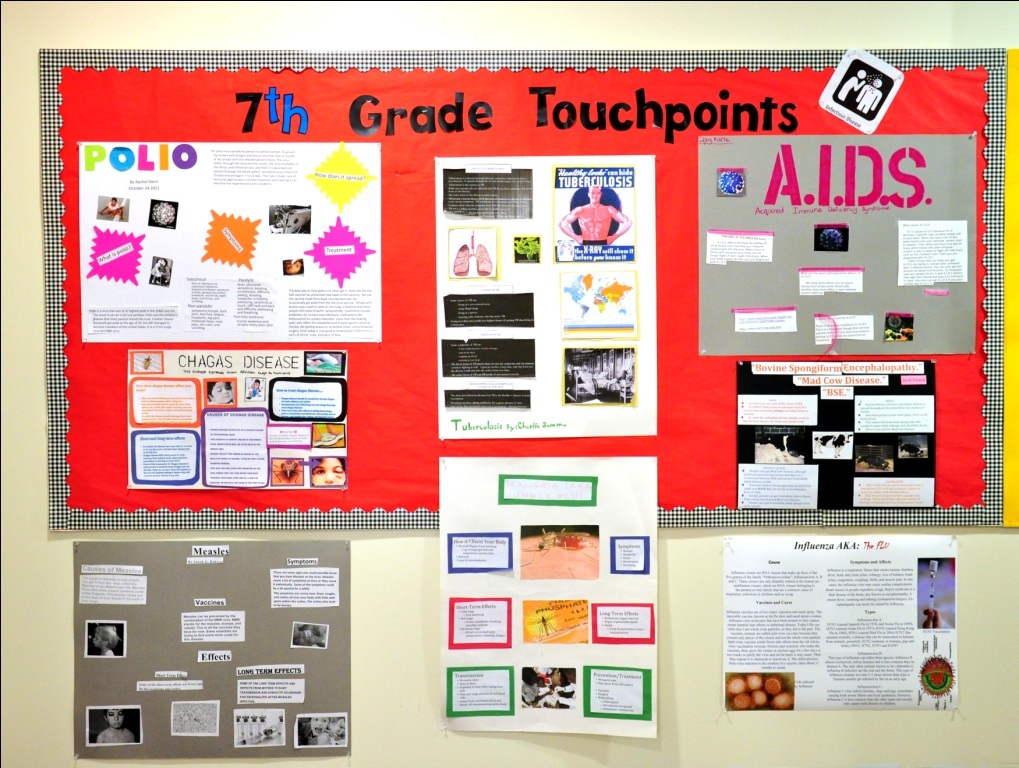

The “Touchpoints” program at Léman Manhattan Preparatory School extends from second grade through eighth grade and gives students the chance to examine issues that apply to not only their neighbors within the city, but also their neighbors around the world.

Colleen Brown, the Touchpoints Coordinator at Léman, said the program’s “purpose is to create global awareness of what’s going on around” the students.

Brown was a science teacher and the school nutritionist for Claremont Prep. Last year Claremont was bought out by Meritas, which has schools in Mexico, Switzerland, China, as well as in four other states in the U.S. When she first learned of the “Touchpoints” program, Brown said she instantly saw its potential but was intrigued by the manner in which it would be realized.

“I thought, wow, this is obviously an amazing program, but it will be interesting to see how it works,” said Brown.

It turned out that the way it worked was quite simple as long as one could comprehend how far technology in the classroom has come in recent years. For example, students use “wikis,” websites where users can upload, update and share content, designed for their specific topic so students at all of the Meritas schools can see what their peers are doing. Students produce introductory videos that are posted on the sites and that can be viewed by students in the other schools around the world.

Students then Skype, or video chat online, with the other students about their projects, as well as work with their parents and teachers to generate ideas on overcoming any obstacles they might face. A “professional” is then brought in to give a lecture to the students in each grade on their specific topic and the lectures are posted on the wikis so students in all of the schools can view them. The entire year culminates in what is called the “Great Debate,” where a class at Léman is paired with another Meritas school for a virtual “Lincoln-Douglas” style face-off.

This year, the fifth grade class at Léman tackled the fight against poverty. Their great debate will focus on the point that “most of the poverty in the First World (developed nations) is caused by poor personal decision-making.”

Part of the program also includes a “great experiment” tied directly to the topic and that involves a community service component.

“The [fifth-grade] students had to design a menu to feed a family of four for an entire month on a budget of $25,” said Brown.

One of the first realizations, according to Brown, concerned the types of food the students could get that would last a full month.

“They realized they couldn’t just buy a box of Cheerios,” said Brown, “and instead they had to buy the generic ones. And they had to buy dried beans, for example, to get the most for their dollar. And they couldn’t buy fresh fruit. They had to buy canned fruit.”

After the students bought their food, they boxed it all up and delivered it to a local fire station where it was then picked up by City Harvest and delivered to needy families just before the holidays.

Brown said part of the learning experience was making the kids ask tough questions like, “What if you don’t like beans? Do you really have the option of not liking things when you’re on such a tight budget?”

Brown said it was definitely eye opening for a lot of the students, some of which she said sometimes complain if they have to eat the same thing in the cafeteria two weeks in a row.

As a teacher, Brown said it was a “proud moment,” watching the students work on the project.

“Just having them talk about these global issues and watching them think through things … they were actually turning into global kids.”