By Julie Shapiro

Volume 22, Number 28 | The Newspaper of Lower Manhattan | November 20 – 26, 2009

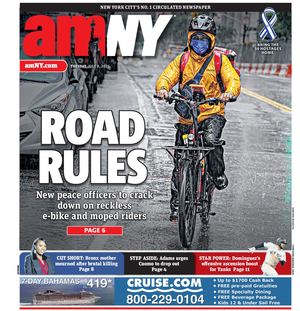

Magna whata? Mild interest in the ‘document that changed the world’

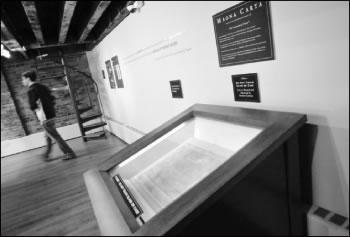

The 800-year-old document credited with birthing democracy has been in town for two months, but not very many people have come to see it.

The Magna Carta is arguably one of the most important documents in Western civilization, and the Fraunces Tavern Museum is marketing its display in New York as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for New Yorkers and tourists alike.

“It’s the foundation of everything,” said Norman Liss, an honorary chairperson of the exhibit. “It’s the first document referring to individual freedom.”

Signed by King John of England in 1215, the Magna Carta marked the first time a king agreed to limits on his power and acknowledged the rights of his noblemen. America’s Founding Fathers were inspired by the Magna Carta and included many of its provisions in the Bill of Rights.

But beyond school groups and private evening receptions, the exhibit has only attracted about 2,800 visitors since opening on Sept. 15.

“Those of us that have seen it have been a little disappointed,” said Roger Byrom, chairperson of Community Board 1’s Landmarks Committee. “The turnout is rather on the low side of what they were expecting.” Byrom, who is British, said although the museum predicted hundreds of thousands of visitors, “There’s nobody there.”

It’s not clear if the museum was really expecting that many visitors, but officials perhaps were hoping for more people in two months than visit Battery Park in one day. Curator Suzanne Prabucki said the attendance is strong for the small Pearl St. museum, which is housed in Manhattan’s oldest surviving building and focuses on the American Revolution.

One reason for the low number of visitors could be that people haven’t heard of the Magna Carta. French, Belgian and German tourists in Battery Park all gave blank stares when asked about the British document. A 40-year-old man from Dallas tilted his head back and said, “I’ve heard of the Magna Carta, but I don’t know too much — not as much as I should.”

At one time a fundamental part of history curriculums, the Magna Carta has taken on a less prominent role. Jennifer Patton, the museum’s education director, said the Magna Carta is generally mentioned briefly when students learn about the American Revolution, but it is not put in enough context for students to remember it.

“World history has always been a problem — when I was in school and still,” said Patton, who is 29. “For kids, it’s difficult for them to understand that this was done before America was even known of.”

On a recent Friday afternoon, just two visitors, both New Yorkers, were bent over the Magna Carta’s temperature and humidity-controlled glass case at Fraunces Tavern Museum. Marguerite Oerlemans, who is in her 40s, said her father had dragged her to the exhibit.

“I knew it was old,” Oerlemans said of the Magna Carta. “I knew it was a significant something-or-other.”

Her father Walter Oerlemans, 80, grew choked up as he pored over the curling Latin script.

“I find it moving,” he said. “To see the real thing — it’s like going to the Met and seeing a Rembrandt. I wish I could read it.”

The museum had a few more visitors Sunday afternoon, including a pair of 23-year-old self-described history buffs, among the youngest patrons at the exhibit not brought by their parents. Unlike some of their peers, Jenny Hollenberg, from Murray Hill, and Jeffrey Douglas, from Long Island, said they couldn’t imagine not knowing about the Magna Carta.

“It’s just one of those dates you remember,” Hollenberg said of the year 1215.

Douglas said he was surprised by how physically small the document is, and how well it has been preserved over the past 800 years. Of the four known copies of the Magna Carta, the one visiting the Fraunces Tavern is in the best condition, and the writing is clearer than on more recent documents like the Declaration of Independence.

This copy of the Magna Carta usually sits in England’s Lincoln Cathedral. Several English tourists in Battery Park, who had not heard of the exhibit, said it would be easier for them to just visit the Magna Carta at home.

“I don’t think I came to New York to see the Magna Carta,” said Elizabeth Sykes, 68, from England.

Some visitors from across the pond may also have been hesitant to go to a museum focused on the overthrow of an English king.

“You feel like you’re on enemy territory, almost,” said Victoria Keating, 39, an English ex-pat who braved the exhibit with her mother and friend last Sunday. Keating said that when she visited the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia, some of the guards jokingly gave her a hard time, but no one bothered her at Fraunces Tavern.

The Fraunces Tavern Museum is just a couple blocks from Battery Park, where crowds of tourists pose with costumed versions of the Statue of Liberty and drape themselves in symbols of American patriotism — but it was hard to find people there who had heard of the Magna Carta. Two of the men in Lady Liberty gear just shook their heads when asked about it, though the third, Fernando Riano, 34, nodded eagerly.

“Yeah, I heard about it,” he said through his skintight green mask. His wife had told him about the exhibit, and he planned to go see it. “It’s important,” Riano said. “It’s interesting.”

In addition to displaying the Magna Carta, the Fraunces Tavern exhibit explains its context and draws connections through the present day. The Magna Carta was an agreement between King John and a group of barons, based on many specific grievances the barons had with the king’s unlimited power. Latin for “Great Charter,” the document spelled out rights to property and a fair trial — but only for noblemen, not commoners.

As such, the Magna Carta was just the first step toward universal rights, and the museum’s exhibit points out that many groups still have not achieved equal protections under law. Visitors can leave their own examples behind on Post-it notes, and have recently mentioned animals, the homeless, immigrants and the mentally ill.

Several older visitors of the exhibit lamented that the younger generation does not know enough about history in general and the Magna Carta specifically. But a few young tourists in Battery Park were defensive, rather than sheepish, when asked about the Magna Carta in Battery Park.

Vicky Patinl, 21, from Los Angeles, said there is no reason to pay attention to history lessons, because schools teach sugarcoated versions anyway. She recalled learning about Christopher Columbus as a heroic pioneer, only to find out later that he gave the natives smallpox-infected blankets.

“They might as well not even teach history,” Patinl said. “Why bother teaching something that’s not even true?”

The Magna Carta is on display through Dec. 15 at the Fraunces Tavern Museum, 54 Pearl St., Tuesday to Sunday 12 p.m. to 6 p.m. Tickets for adults are $10, seniors and children 6 to 18 are $5 and children under 5 are free.

Julie@DowntownExpress.com