by Candida L. Figuerora

There were repeated fires at the former Deutsche Bank building in the 10 weeks before a smoky blaze killed two firefighters, and the Lower Manhattan Development Corp. was warned by its own consultant that the building was “an accident waiting to happen.”

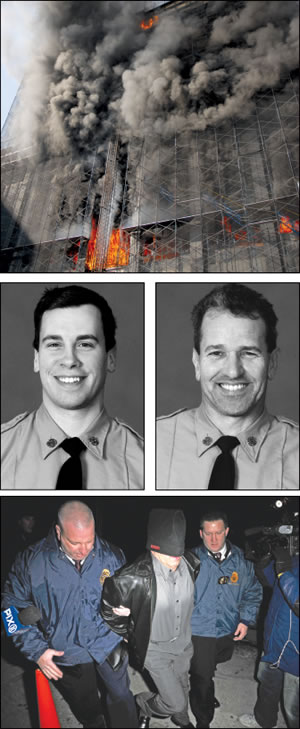

But the nine small fires in the chaotic spring and summer of last year did not spark enough action to prevent the one on Aug. 18, 2007 that tore through the building, suffocating firefighters Robert Beddia, 53, and Joseph Graffagnino, 33, of the Engine 24 firehouse in Soho.

The Fire Dept. never knew about the nine small fires that preceded the deadly one, because contractor Bovis Lend Lease and subcontractor John Galt Corp. put out the fires quietly, without calling 911. The L.M.D.C., the state-city agency that owns the building, and the city Dept. of Buildings, which had inspectors in the building every day, knew about several of the fires but did not notify emergency officials or the public.

These were among the conclusions in a 32-page report District Attorney Robert Morgenthau released Monday, capping the first part of the 16-month investigation. Morgenthau also announced the indictment of John Galt Corp., two Galt employees and one Bovis employee for manslaughter, criminally negligent homicide and reckless endangerment.

Bovis, the city and the L.M.D.C. will not face criminal charges in connection with the fire, but the L.M.D.C. and its subsidiary, the Lower Manhattan Construction Command Center, are still subjects of a separate grand jury fraud probe, according to Morgenthau’s office. Bovis and the city both acknowledged responsibility for their failures as part of an agreement with the D.A. Morgenthau said he had concerns that indicting Bovis, one of the city’s largest contractors, would have had a devastating effect on the economy.

“Certainly that was a consideration,” he said. “The federal government, I think, made a huge mistake when they indicted Arthur Andersen and there are six people [culpable], and they put 30,000 people out of work.”

He said if found guilty, Bovis would have had to pay a minimal $10,000 fine, and instead the firm agreed to more stringent safety measures in addition to acknowledging wrongdoing.

Civil liberties attorney Norman Siegel, who represents the Skyscraper Safety Campaign, and others were outraged by this argument. “Since when is wrongful and negligent conduct excused because of economic conditions,” he asked.

Joseph Graffagnino Sr., whose son was killed in the Deutsche Bank fire, wants to see Bovis charged along with the many government agencies that oversaw the project.

“No one is holding them responsible, and I think that’s an outrage,” Graffagnino said. Referring to Bovis, he asked, “How can you indict a worker and not indict the company?”

Alexander Santora, whose son was a firefighter killed on 9/11, agreed that the D.A. did not go far enough.

“These two men died for no reason,” he said. “Who is standing up and screaming? You would hope it would be the D.A. going after the culprits…. They zeroed in on some low-level people. It’s just a travesty of justice.”

Morgenthau acknowledged many people beyond those indicted made errors that led to the fire.

“Anybody who could have screwed up, screwed up here,” Morgenthau said. “It’s just amazing the number of mistakes made.”

Morgenthau called the fire a “perfect storm” in which so many people and agencies were responsible that, in effect, no one was responsible. It’s a phrase officials have used before in explaining events during the tortured and tragic saga of the building, which was badly damaged by the collapse of the Twin Towers seven years ago.

A worker’s discarded cigarette sparked the fatal fire as the contaminated building at 130 Liberty St. was being simultaneously cleaned and demolished. Firefighters had no water to battle the fire for the first hour they were in the building because Galt had removed portions of the standpipe, which is used to pump water to upper floors. Galt also blocked off the stairways with plywood and sheets of plastic, making it impossible for firefighters to escape once they realized they were caught in a death trap. The 41-story building had been demolished down to the 26th floor at the time of the fire.

Morgenthau’s report also revealed other disturbing details:

• On Aug. 3, 2007, the day of the seventh small fire, construction monitor URS Corp. told the L.M.D.C. the building was “an accident waiting to happen” and Bovis could no longer be trusted to keep the building safe.

• Bovis removed a scrupulous site superintendent, who did a thorough test of the building’s standpipe in 2006, and replaced him with a superintendent who cared less about safety.

• Under Galt’s implementation plan, the stairway barriers were supposed to have kick-out panels, but they did not and were very difficult to penetrate. The panels were also supposed to be built vertically, as walls, rather than horizontally, as floors.

• Several F.D.N.Y. officials sent memos to their higher-ups recommending an emergency firefighting plan for the building, but the memos were ignored.

• Galt was supposed to hire a site safety manager for the project but never did so, and Galt executives rushed the work at the expense of safety.

Both the city and Bovis signed statements saying they did not challenge any of Morgenthau’s assertions. The L.M.D.C., which hired Bovis and authorized the Galt contract, did not comment on Morgenthau’s conclusions.

The nine small fires that started in the Deutsche Bank building between June 11, 2007 and the week before the Aug. 18 fire could have served as sufficient warning to all parties involved that the project needed drastic safety changes. From the outset, Bovis acknowledged that the building was a fire risk. The torches used to cut steel and concrete often sent drops of scalding metal onto combustible materials on lower floors. Showers of sparks and metal set nine fires, all minor but forming a pattern that should have caused growing alarm, the D.A. charged.

On July 31, the same day as the sixth of these fires, a steel pipe fell six floors down the building. That was two months after another steel pipe fell off the top of the building and crashed through the roof of the 10/10 firehouse next-door, injuring two firefighters.

The Buildings Dept. did not issue any fire-safety violations to the project after any of the small fires. On Aug. 1, the Buildings Dept. issued a stop work order because blow torch sparks landed too close to combustible materials but did not cause a fire. Downtown Express first reported this violation on Aug. 16, 2007, two days before the deadly fire.

The earlier May pipe crash was one of a few public hints in the spring of ’07 that building safety was out of control. In June, Charles Maikish, who was then the head of the Construction Command Center, told Community Board 1 that the crash occurred as a result of a change in procedure implemented to speed the work, which was first reported by Downtown Express.

It was also around this time that Maikish sent a memo to Avi Schick, the L.M.D.C.’s chairperson, saying he did not have enough staff to properly monitor the project. The existence of the memo did not come to light until after the fire, and the L.M.D.C. says it has no record of ever receiving it from Maikish, who headed the corporation’s subsidiary.

The standpipe

While the D.A. lambastes the contractors and agencies for failing to heed the many warnings, he highlights the absence of a working standpipe as the one fact above all others that caused the firefighters’ deaths.

Galt began abating the asbestos in the basement of the Deutsche Bank building in the summer of 2006, essentially clearing the space of every speck of dust and debris. The environmental regulators held Galt to very strict cleanliness standards, which soon caused delays and tension between the contractors and the regulators.

The basement ceiling was a tangle of pipes, some of which would be cleaned superficially and removed, and others that had to be cleaned more thoroughly so they could remain. The standpipe was known as an “untouchable pipe,” never to be removed.

But Galt supervisors grew frustrated with the slow pace of work on the standpipe, which was attached to the ceiling by supports that had to be cleaned by hand with small wire brushes. Around the fall of 2006, Galt supervisors sawed off several of the supports to avoid having to clean them.

“It was a decision with deadly consequences,” Morgenthau said.

As workers sawed, one piece of the standpipe fell to the ground with a clatter, while another section hung precariously off kilter.

The three men indicted Monday — Salvatore DePaola, Galt’s foreman; Mitchell Alvo, Galt’s director of abatement; and Jeffrey Melofchik, Bovis’ site safety manager — gathered with a crowd of workers around the wreckage and decided to remove the fallen and dangling pieces of the standpipe, according to Morgenthau. That left a 42-foot gap in the system, rendering the entire thing inoperable. That was a secret the three men and other workers kept for nearly a year, until firefighters discovered it the following summer as they searched desperately for water.

There were plenty of chances for someone to discover the broken standpipe earlier.

“You didn’t need a magnifying glass to see the gap,” Morgenthau said Monday. With most of the pipes cleared out of the basement by December 2006, the standpipe was clearly visibly and the missing segment was impossible to overlook.

But the Buildings Dept. and F.D.N.Y. never ventured into the basement. D.O.B. inspectors were on the site every day, but they never once went into the northeast corner of the basement, where the standpipe was. The D.A.’s report says the Buildings Dept. assigned inexperienced inspectors to the site. Morgenthau said there was no evidence to suggest the rush to take the building down pressured inspectors from various agencies not to do full inspections.

The F.D.N.Y. was also supposed to inspect the building every 15 days while it was being cleaned and demolished, but the F.D.N.Y. made no thorough inspections between 9/11 and the fire nearly six years later.

The D.O.B. did not discipline or reassign anyone after the fire because the D.A. asked the city to wait until the criminal investigation was complete, said Jason Post, spokesperson for the mayor’s office.

“Now that the D.A. is done with his work, we will conduct our own internal inquiry,” Post said.

The F.D.N.Y. reassigned three supervisors after the fire — Deputy Chief Richard Fuerch, Battalion Chief John McDonald and Captain Peter Bosco of Engine 10 next to the building. A spokesperson said McDonald has since retired and an investigation will now begin into the other two supervisors. Morgenthau said Bosco’s company was never given the Haz-Mat suits they would have needed to do a full inspection.

Bovis’ Melofchik made the situation worse by lying about the standpipe’s condition, according to procecutors. In hundreds of daily project checklists, he certified that the standpipe was operational. He also said the building had clear emergency exit paths, though the staircases were sealed.

Melofchik’s superiors “blindly relied” on these checklists, the D.A.’s report states, even though after the fire it became clear they were fraudulent. The computer-generated checklists are virtually identical, varying only in the date and Melofchik’s initials, which were sometimes forged.

The indictments

Monday’s indictments could have brought a measure of justice and comfort to the victims’ family members, but instead they see the fight as far from over.

The elder Graffagnino, whose son was killed in the fire, thinks Bovis, the city and the L.M.D.C. all should have been indicted.

“They’re using Galt as a scapegoat,” Graffagnino said. “You don’t waste 16 months of taxpayer money just to dump on a scapegoat — you could’ve done that the first day.”

Graffagnino and the family of Beddia, the other firefighter killed, are filing civil suits against the contractors and government agencies.

“That’s the only way to hold the city accountable,” said Michael Barasch, lawyer for the Beddia family. “We want to hold everyone’s feet to the fire and get some answers: what happened and what changes to make to make sure it never happens again.”

Morgenthau faced a barrage of questions Monday on why he did not indict Bovis or the city. The city is protected by sovereign immunity, which makes it almost impossible to charge them. Morgenthau said the incompetence at the city was endemic and therefore hard to pin on specific officials, and going after the city as a whole would be like “tilting windmills.”

Siegel, the attorney who represents the Skyscraper Safety Campaign, said he was “perplexed” by Morgenthau’s reasoning since police officers are often charged with crimes committed on duty. A D.A. spokesperson said sovereign immunity applies only to agencies and high-ranking officials, not to lower-ranking workers like police officers, firefighters and building inspectors.

The D.A.’s report implicates high-ranking officials at the F.D.N.Y., but Kim Berger, deputy commissioner of the Department of Investigation, refused Monday to say how high up the mistakes went and whether they extended to the mayor, fire commissioner and buildings commissioner. She also refused to say if anyone was disciplined.

Morgenthau barely mentioned the L.M.D.C. at Monday’s press conference, and the agency is the only party heavily involved in the Deutsche Bank building that has not taken any responsibility for the fire.

Daniel Castleman, chief assistant D.A., said a separate grand jury is examining the L.M.D.C. and its subsidiary, the Lower Manhattan Construction Command Center, as part of a “fairly broad” investigation. The probe is likely centered on why the L.M.D.C. approved Bovis’ hiring of Galt, a shell company whose executives had reported mob ties. In 2006, the city Department of Investigation told the L.M.C.C.C. that picking Galt was a bad choice. The D.O.I. accused Maikish, head of the L.M.C.C.C., of misleading investigators about Galt’s identity.

While the D.A. only indicted one Bovis employee — Melofchik, the site safety supervisor — the D.A.’s report makes it clear that he was not the only one to act inappropriately. Melofchik’s supervisors turned a blind eye to safety, and other Bovis employees forged Melofchik’s initials on daily safety checklists.

Instead of charging the city and Bovis, the D.A. negotiated a number of concessions from each of them, which Morgenthau said would have been impossible through criminal litigation.

To complete the investigation, the D.A.’s office interviewed more than 150 people, examined more than 3 million documents and presented more than 80 witnesses to a grand jury.

Melofchik, 47, Alvo, 56, and DePaola, 54, surrendered to police Monday morning and pleaded not guilty at their arraignments Monday afternoon. They each face two counts of second-degree manslaughter, two counts of criminally negligent homicide and one count of reckless endangerment. John Galt Corp. faces the same charges. The maximum penalty for the manslaughter charge is 15 years in prison.

The defendants are free after posting bail: $250,000 each for Melofchik and Alvo, and $175,000 for DePaola. They are due back in court Jan. 7.

Attorneys for Melofchik and Alvo both said their clients were being made “scapegoats” for the long list of mistakes made by the government agencies cited in Morgenthau’s report.

“Mr. Morgenthau himself admitted that the fire was a perfect storm, and that everything that could have gone wrong went wrong,” Melofchik’s attorney, Edward J.M. Little, said in a lengthy prepared statement. “The real responsibility here belongs to federal agencies, city agencies and even the Fire Department itself, as Mayor Bloomberg has also admitted….

“The District Attorney’s reluctance or inability to indict federal and city agencies for their malfeasance is no excuse for making Jeff Melofchik…a scapegoat for all these unfortunate circumstances….We are confident that Jeff will be vindicated.”

DePaola’s attorney also said his client would be cleared.

With reporting