By Julie Shapiro

For seven years, 3,000 miles stood between Susanne Ward-Baker and her son Timothy’s remains.

Timothy Ray Ward, 38, was flying from Boston to Los Angeles on the morning of 9/11, on United Airlines Flight 175. After the plane slammed into the World Trade Center, all that was found of Ward were three shards of bone.

For seven years, those three pieces of bone sat in a Ziploc bag in a freezer at the New York City Medical Examiner’s office, waiting to be claimed. For seven years, Ward-Baker made phone calls to New York from her house in San Diego, searching a way to bring her son home.

“I’m just a mother who wants my son’s little teeny pieces of bone with me,” Ward-Baker told Downtown Express several weeks ago, beginning to cry during a telephone interview.

Ward-Baker, 67, finally got her wish on Nov. 14, when a seven-year impasse ended and her son’s remains arrived.

Last week Ward-Baker sat in her home in San Diego looking at the cherry wood box containing what’s left of her son, reflecting on the years of being separated from him.

“I can’t believe what-all I’ve been through,” she said. “I just can’t believe this is real.”

The Medical Examiner’s office identified Tim Ward several months after 9/11. While for many families, the identification of remains marked the beginning of closure, for Ward-Baker, it marked the beginning of a seemingly impossible struggle. Funeral homes quoted prices in the thousands of dollars to transport Ward’s remains, and lawyers told her the pieces of bone would have to be cremated, an idea Ward-Baker could not stand.

“They’ve already been cremated,” she said, referring to the conflagration when his plane hit the South Tower. “Why do they want to burn my son’s little tiny bones?”

Ward-Baker said one funeral home she called said they would need to use a hearse and stretcher to transport her son’s remains, necessitating a $3,500 price tag. She tried to explain that there was no corpse, only three bones, but they were rude and inflexible, she said.

“You can pick my son up in a rickshaw, as long as he’s treated with respect,” Ward-Baker said, her voice brightening momentarily. “He’d get a kick out of that.”

But she quickly turned serious again.

“It’s not even about the money,” she said. “It’s about these mortuaries trying to make a great big profit off of tiny shreds of bone.”

Ellen Borakove, spokesperson for the New York City Medical Examiner, said she had never heard of another battle like Ward-Baker’s. Of the 2,751 people killed at the World Trade Center on 9/11, 1,622 people have been identified. The city is still holding thousands of remains that have not been identified, along with many identified remains. But the city usually only holds identified remains if the family wants to wait to claim them or wants them to eventually be placed in the 9/11 memorial, Borakove said.

Leslie Francisco, owner of Francisco Funeral Home in Ozone Park, was horrified to hear of Ward-Baker’s struggle. She worked with the Medical Examiner’s office after 9/11, a particularly sensitive issue for her because her son was a paramedic with the Fire Department who rushed to the burning towers. He survived, but his partner in Tower 2 did not.

“There is no law saying a funeral home can’t charge full cost for this, but I would never do that to a 9/11 victim,” Francisco said.

The other funeral homes were thinking of Ward’s remains as though they were a complete body, in which case they would have to be embalmed or cremated in order to be shipped.

“But we’re not talking about a normal circumstance — we’re talking about three bone fragments,” Francisco said. “They’re going by the letter of the law because technically that puts more dollars in their pocket.”

Ward-Baker said a month ago she had all but lost hope that she and her son would be reunited. Then Francisco told Downtown Express she would do the job for minimal costs, but that turned out not to be necessary. Around the same time, Ward-Baker remembered an old friend she hadn’t spoken to in years, who had once been a medical examiner in San Diego.

Several weeks ago, he put her in touch with Dan Williams, a manager at Greenwood Memorial Park and Mortuary in Southern California.

“When I heard her story, it was heartbreaking,” Williams said. “To think she’s waited as long as she has, and come up against obstacle after obstacle… She needed to have some closure. She needs to have Tim home.”

Williams made a few calls and found an affiliate in New York City owned by his company. Charles Salomon, president of Riverside Memorial Chapel on the Upper West Side, agreed to help on the spot, and he promised not to charge any extra fees.

“We recognize the tragedy — we’re not here to capitalize on that sort of thing,” Salomon said. “It’s an opportunity to step forward, be part of the community and act accordingly.”

Once Williams and Salomon were on board, everything began happening quickly. Salomon picked up the remains at the Medical Examiner’s office and shipped them to Williams, where they arrived two weeks ago. Greenwood Mortuary drove Ward’s remains to his mother’s house on Nov. 14, finally bringing him home. The total cost for paperwork, shipping and an engraved box came to a little over $400.

“It feels wonderful,” Ward-Baker said, though she choked up as she described memories of her son.

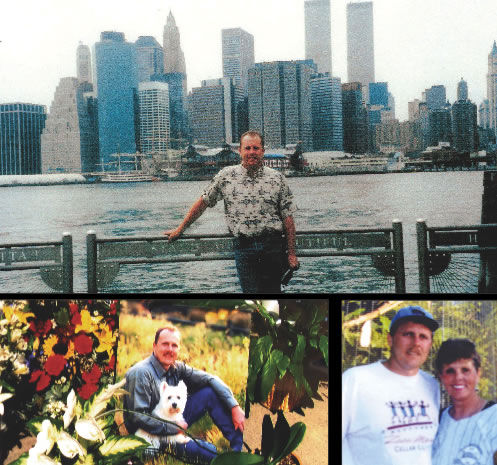

Tim Ward was an only child, born on Valentine’s Day in 1963. He was an agreeable boy who loved playing any sport, from flag football to baseball. Tall and blond, he played varsity basketball in high school and was voted president of his class. At San Diego State, Ward studied computer science and rooted for the football team — a tradition he continued after graduation, when he traveled around the country to see the team play as often as he could.

After college, Ward went to work at Rubio’s, a Mexican food chain based in Southern California. He started as a manager at one of the restaurants and rose to a computer systems analyst in the corporate office.

As a young boy, Ward liked helping his mother cook, a hobby he continued as he grew. He whipped up gourmet dishes with caviar and once cooked a wild turkey for Thanksgiving. Ward would bring Caesar salad and marinated chicken to football tailgates, and his homemade cheesecakes were the center of any gathering.

Ward himself, though, preferred to stay out of the limelight, his mother recalled. He could carry on a conversation but didn’t like it to be only about him. He never yelled at anyone at work, to the point where his boss once urged him to get angry.

Ward took a trip to New York City in May of 2001, where he was photographed with the Lower Manhattan skyline in the background, the Trade Center towers standing eerily behind him. He returned to the East Coast several months later to visit his girlfriend of 12 years, who was in Boston on a business trip. From Boston, he wired his grandmother a bouquet of flowers on Sept. 9, Grandparents’ Day. On the morning of Sept. 11, he boarded United Airlines Flight 175, bound home to Southern California.

In the wake of 9/11 and the years that followed, Ward’s friends and relatives have left comments on an online guest book, describing his smile and gentle manner, promising to remember him.

“He was such a sweet guy…fiercely loyal to his friends…the kind of guy who would come pick you up at the airport or let you crash on his couch without thinking twice,” wrote Michele Hintz, a former co-worker.

Last week, Ward-Baker recounted standing in front of her home in Escondido, Calif. on Nov. 14, her long wait nearly over, the Greenwood Mortuary about to arrive with her son’s remains. She and a friend placed four American flags in the planter outside her front door, beneath the larger American flag flying above.

“It looked like the president was coming or something,” Ward-Baker said.

The car from the funeral home pulled up, and one of the men told Ward-Baker to wait inside the house. After a moment, he followed her and placed the canister before her on the island in her kitchen.

“I just went up to it and put it in my arms and held it close to my heart,” Ward-Baker recalled, her voice faltering. “I got a little emotional, then I was okay. I’ve been gearing myself up for this — not to collapse.”

The three pieces of bone are in a cherry wood box, engraved with Ward’s name, dates of birth and death, and the flight number. Ward-Baker placed the box in a memorial she created years earlier, a hutch filled with photographs of Ward, American flags, cards from school children and a piece of W.T.C. steel.

When Ward-Baker dies, she plans to be cremated and have her remains placed with her son’s.

While Ward-Baker said it has been a relief and a blessing to have her son’s remains at home, her sense of loss still feels fresh at times. The other night she dreamed her son was alive and they were laughing together, over something she doesn’t remember. In the morning, Ward-Baker had trouble leaving her bed.

“I didn’t want to get up,” she said. “I wanted to go back to dreaming about it.”

Julie@DowntownExpress.com