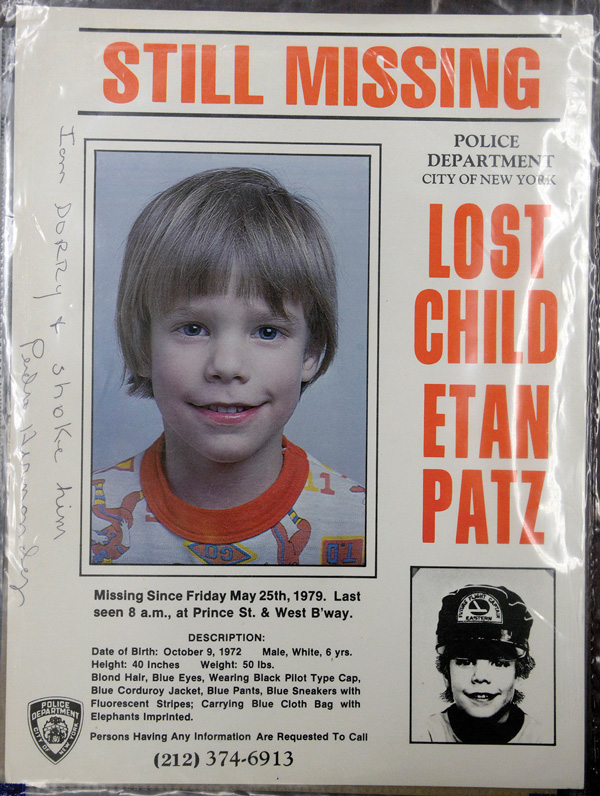

BY LINCOLN ANDERSON | As the trial of Pedro Hernandez in the Etan Patz case continues in court, it has cast a focus back on the neighborhood of 35 years ago, when the 6-year-old Soho boy tragically disappeared while on his way to school by himself for the first time.

Hernandez’s trial began Jan. 5 and, from the outset, was expected to be lengthy.

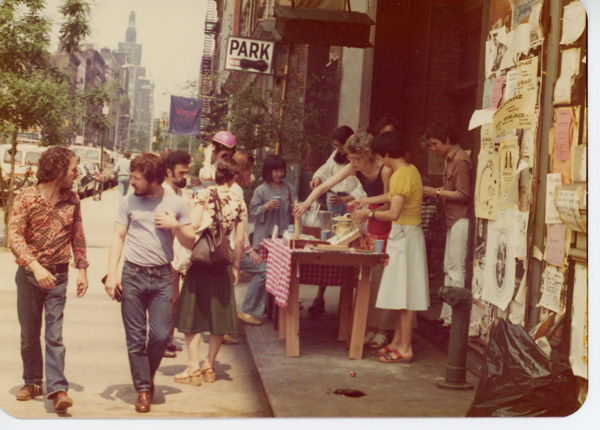

Soho residents from that earlier era vividly recall the events following Patz’s vanishing, as well as the gritty, artistic enclave that Soho once was.

On the morning of May 25, 1979, Etan Patz left home on Prince St., and was last seen walking west toward West Broadway, two blocks away, to catch the school bus to P.S. 3, a dozen or so blocks distant at Hudson and Grove Sts.

At the time, Hernandez worked at a bodega — long since closed — at the northwest corner of Prince St. and West Broadway that was one of Soho’s primary food depots. The school bus stop was located just north of there, midway down West Broadway toward Houston St.

The prosecution charges that Hernandez confessed to police that, with the promise of a free soda, he lured Patz into the bodega’s basement. There he strangled him, then bagged and boxed the boy’s body, then dumped him in an alley on Thompson St.

After confessing to police, Hernandez subsequently led detectives along the street from the former bodega’s corner to show them the spot where he claimed he left the body.

Julie Patz, Etan’s mother, testified in court that her son had planned to get a soda at the bodega that day before boarding the bus.

Relatives and church group members say that over the years Hernandez has claimed to have killed a child.

The defense, meanwhile, contends that Hernandez has a very low I.Q. of 70 and is thus mentally disabled, plus is mentally ill, and made up the story under pressure from police. His lawyers counter that Jose Ramos, a homeless man who hung around Soho and was the boyfriend of the Patzes’ babysitter — and who was long the prime suspect — is, in fact, Etan’s killer.

No one from the neighborhood, however, seems to recall Hernandez at all.

“I don’t remember that bodega worker, but I do remember that bodega,” said Penelope Grill, who used to live on Prince St. between Mercer and Greene Sts., a block away from the Patzes. “It was one of the only places you could shop in the neighborhood.”

She also clearly recalls the police search for Etan.

“The detectives came around knocking on my door,” she said. “They were going through all the residences in the neighborhood, especially where there were men living. They mentioned Etan Patz, and they asked me through my door if I lived alone, and I said, yes. When they saw it was just me, a woman, they left.”

Grill, a painter, was creating craft items back then in her home, which like the rest of Soho, had been zoned for joint artists’ living/working quarters.

She recalled how she used to see Julie Patz and her children, and possibly other neighborhood kids along with them in tow, along the street, scavenging squat cardboard fabric spools left by fabric warehouses. The spools had been cut down into segments and could be used for constructing platforms for beds or tables, she said.

“We were scavengers,” she said. “We all were. … It was much more deserted then.”

In 1993, Grill moved back to her native Wisconsin to take care of her ailing mother.

Caroline Keating, again, recalls the bodega but not Hernandez. On the other hand, she well remembers Juan Santana, his brother-in-law, who also worked at the store, and who still is a familiar sight in Soho.

“I remember Juan, who became the manager of most of the buildings over there,” she said. “Juan took care of the building next to us. He took care of buildings everywhere. Juan ran the bodega back then. He didn’t own it.

“He really was kind of ‘Mr. Soho,’ ” she said of Santana. “Everybody trusted him. He was a man with a very good reputation in the neighborhood who worked like a beaver.”

Keating, a visual artist, recalled the first residential co-op in Soho, at 80 Wooster St. Jonas Mekas started the Anthology Film Archives in its basement.

It was Mekas and a fellow Lithuanian, George Macunias — who went into real estate, though without a license — who “founded Soho,” she said.

Keating moved to the Upper West Side a few years ago when her husband needed to enter an assisted-living facility.

“Juan is an incredibly nice person,” she said. “It’s hard to attach this to him in any way. He was the most empathetic when my husband had a stroke.”

Santana, for his part, has testified in court that he doesn’t believe his brother-in-law did it. First of all, he said, Hernandez never got there before 8 a.m., so wouldn’t have been there at the same time as Patz. Also, he said, the stairs to the basement — which are located outside the building — would still have been locked at that time. In addition, he said, he never saw Hernandez talking with kids, and that he was generally just “a good guy.”

However, the prosecution said Santana was “evasive” on the stand and declared him a hostile witness.

In addition, the prosecution, pointed out that Patz, the day before he disappeared, had left his lunchbox on a stoop by the bodega and had returned to retrieve it, and possibly may have met Hernandez at that time.

According to reports, Santana — saying it was hard to remember from 35 years ago — was vague in his answers as to how long Hernandez had worked at the deli and whether he had left the job the day after Etan went missing.

Santana reportedly got Hernandez the job at the bodega, and when Hernandez worked there, he lived with his sister and her husband, Santana, in an apartment right across the street from the place.

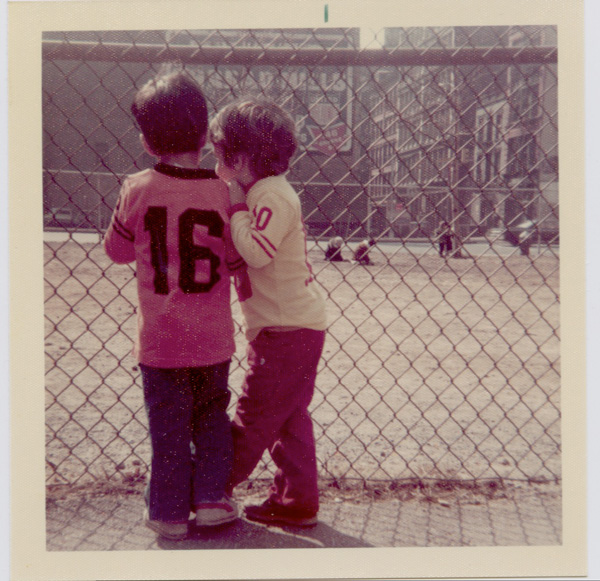

Yukie Ohta grew up in Soho and was two years older than Etan Patz. Her younger sister was the same age as him.

The bodega, Ohta said, was, in fact, considered a safe space by local families.

“It was called ‘the bodega’ because we only had one store,” she said. “We were told to go in there if we were ever in trouble in the street; if someone was following us, we should go in the bodega — because it was the only business that was open. There were a few bars and we were told no, I guess. I think we were told we could go into Fanelli’s if we had issues.”

Ohta, a writer who maintains the Soho Memory Project blog, still lives in the same Mercer St. apartment that she grew up in, around the corner from the Patzes. She also manages her building.

Her dad was an artist who came over from Japan, and her mother emigrated later to join him.

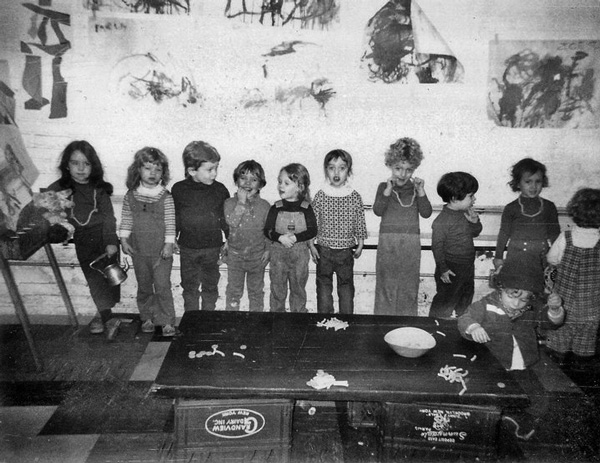

Back then, for daycare, Soho mothers took turns running playgroups in their apartments for kids age two to four. Patz’s mom was part of a “core group” who did this.

Ohta, her sister and Etan all attended the same playgroup for a while.

“Julie Patz had a playgroup in her apartment for a while,” she recalled. “It was like living in a small town.”

Kids also used to play on the open lot that was where the current N.Y.U. Coles gym is today, along Mercer St. north of Houston St., she said.

“As a kid, I never felt in danger,” Ohta said. “It was a daytime neighborhood. The factory workers left at 5. The Soho Artists Association organized patrols and lobbied the city for trash pickup.”

She was eight when Patz was lost.

“I have vivid memories of that specific time,” she said, “when parents held meetings, and did a lot of searching and posters. One of the meetings was in my house.”

Eventually, though, she said, “Things did kind of go back to quasi-normal. I did continue to go to school by myself. I walked to that bus stop with my sister.”

After the playgroups, most of the kids went on to attend P.S. 3, the Charrette School, a specialized arts-oriented school that the community had helped to create. The elementary school has since become more mainstream due to imposition of the core curriculum, Ohta noted.

Like everyone else, Ohta recalls one of Soho’s favorite pastimes from that era: foraging for found furniture.

“We were on the street a lot,” she said. “Everybody scavenged. There were industrial wire spools — so, you could use little ones for chairs and broad ones for tables. There were rolls of industrial carpeting.”

Bill Downey, a longtime Soho resident, said, like the others, he doesn’t remember Hernandez but he does Santana.

“Of course,” he said, “because Juan is one of the mayors of Soho.”

Downey said he didn’t really patronize the bodega because there was another store he went to, on Spring St., that allowed dogs.

“Back then, Soho was like a company town,” he said. “Everybody was in the arts. The highpoint came a few years later, when the galleries came and you could combine walking the dog with keeping up with the art scene.”

When artists first colonized the neighborhood, the buildings were either vacant or home to light-manufacturing uses.

“There were strange, odd little places,” he recalled, “places that bundled up rags. I’ll never forget one place down the street; they had a sign describing themselves as “Manufacturers of Special Machinery for the Chewing Gum Industry.”

Like Grill and Ohta, Downey noted, “Scavenging in Soho in the 1970s was really good — there were work tables, rolling carts. You had really failed if you had to buy your own lumber.

“It wasn’t a big money neighborhood. We moved here because it was so cheap. We bought our loft for $10,000.”

He and his wife didn’t have kids, though, so they didn’t get to know the Patzes.

Today’s glitzy Soho is, of course, completely unrecognizable from before.

“Back then, you felt like you had something in common with your fellow residents,” Downey said. “Now it’s overrun with young money. And being neither young nor rich…it’s a very different community. Back in the 1970s, there probably weren’t more than a couple hundred people who lived in the boundaries of Soho.

“When we moved here in 1972, there were only two residential buildings,” he recalled. “On weekends, when the factories closed, it was like being in the country. You would be the only person getting off the R train at Prince St. You could fire a machine gun down the street and not hit anyone.”

Downey is now on his fourth dog, a terrier rescue, and they amble daily past the high-end stores that supplanted the galleries, which had replaced the factories, and amid the tourist hordes that now teem along the once-empty streets.

“People that have dogs do see the change in neighborhoods,” he reflected.

So do bloggers, like Ohta, with her Soho Memory Project.

“There’s a whole new demographic here,” she said. “Before all the old-timers fade away, I want to document what was here before.”

But that’s not to say Ohta is complaining about having real carpeting and an elevator, unlike when she was a kid.

“That’s New York,” she said of Soho’s changes. “That’s the whole nature of the city. I’m not one of those people who says that it was so much better back then — but I feel it’s worth remembering.”

An unerasable part of those memories — a tragic and painful wound forever inflicted on those more innocent times — is the loss of Etan Patz.