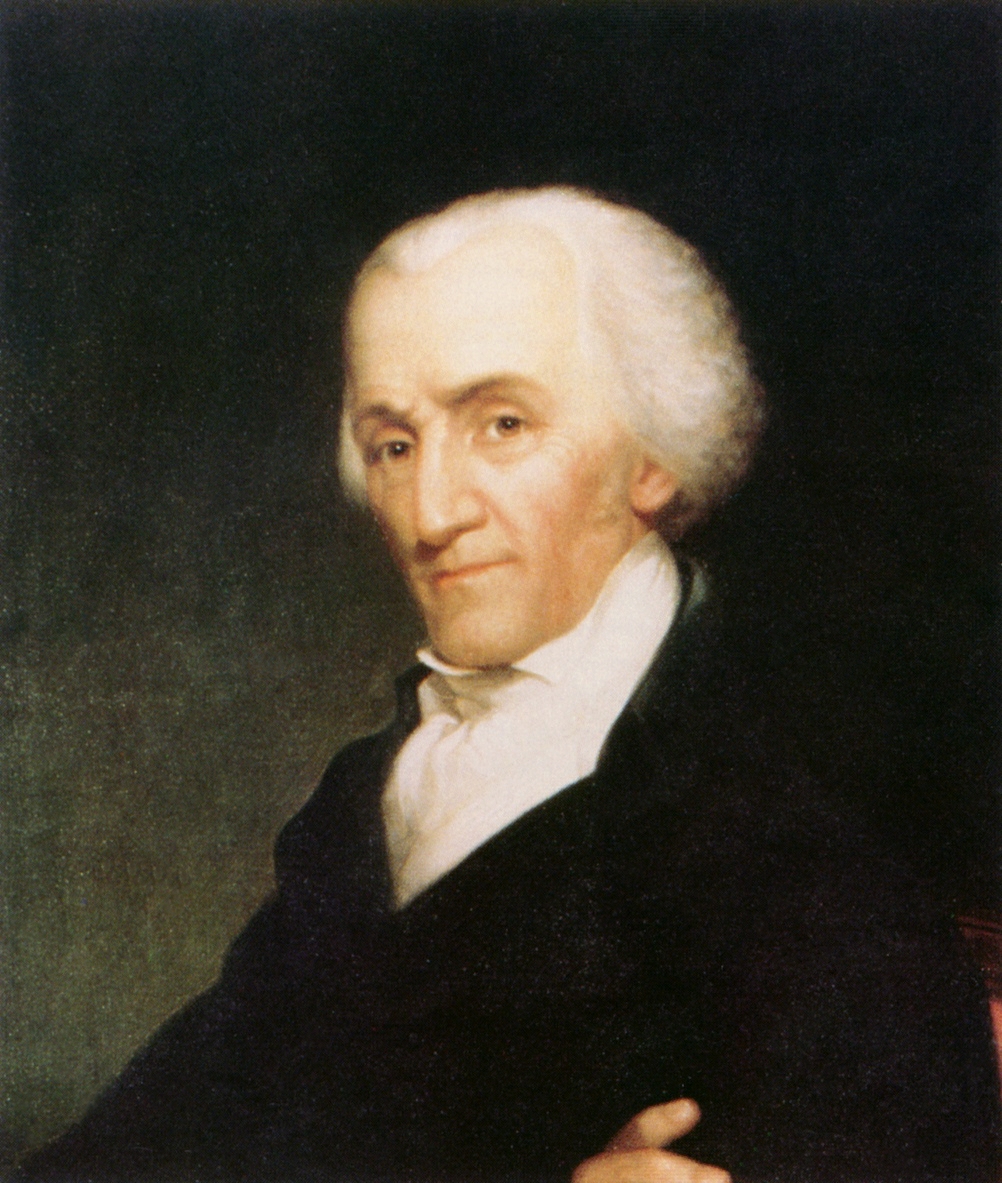

What a shame. He was a congressman, governor of Massachusetts, and vice president of the United States: Elbridge Gerry. Born in 1744 and one of the signers of our nation’s Declaration of Independence, he is remembered as the progenitor and namesake of corrupt line-drawing of congressional and other legislative districts.

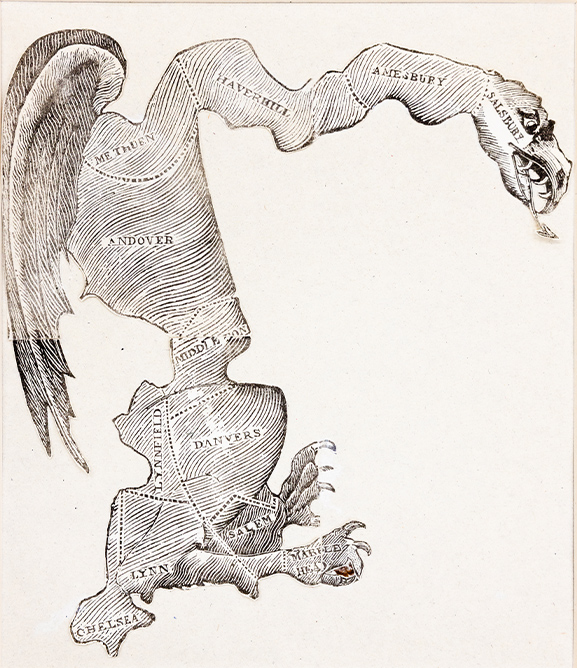

Most readers probably know the story. In 1812, while serving as governor, he approved a redistricting that favored the Republicans at the expense of the Federalists. Why did he do it? By at least one account, he was angry at the Federalists for criticizing the foreign policies of his ally, President James Madison. The hometown reaction, however, was swift. The Boston Gazette conjured up a crazy looking cartoon that resembled a salamander, and pejoratively called it a “Gerry-mander.” Perhaps he had the last laugh — Madison rewarded Gerry a few months later by making him Vice President. Yet, over 200 years later, it is only the Gazette’s characterization that most Americans associate with him.

Adding insult to injury, his name is not even pronounced correctly. The “g” does not sound like a “j” as in Jerry. He pronounced his own name with a “g” as in Gary. The very least we can do is honor his memory by saying his name correctly!

More importantly, Gerry should be lauded for being a staunch patriot who attended the Constitutional Convention in 1787. He worked tirelessly in Philadelphia to ensure that the new country had a strong national government to replace the unpopular, failing confederation then in existence. At the same time, he focused on preserving the prerogatives of the states and the liberties of individuals.

Although he sweated through the proceedings in the Pennsylvania State House as they crafted a new political order, in the end Gerry refused to join 39 fellow delegates in signing the new constitution. He thought that the final product did not sufficiently protect individual rights. Indeed, true to his beliefs, when it came time for Massachusetts to consider ratifying it, he argued for its rejection. But he was not an absolutist. Instead, he urged that a series of amendments be included — what came to be known as the Bill of Rights. His position won the day, and Massachusetts became the first state to adopt the constitution along with its first amendments. Other states followed, and the rest is history.

Shouldn’t we remember Elbridge Gerry for that? Unfortunately for him and his descendants Gerry’s important contributions to history are lost. On the other hand, what politician wouldn’t want to be in the news almost every day as Gerry is?

Ever since President Donald Trump persuaded Texas to redraw their congressional lines this year, lawyers and commentators are crowding the courts and media with accusations of unconstitutional gerrymandering. This mid-decade redistricting, permitted by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2006 in a case also about Texas, led to California doing the same. Other states are focused upon new redistricting as well. How the cases will ultimately shake out remains to be seen, and whether all the line-shifting will have an effect on control of the House of Representatives also depends on factors that will not be clear until late next year.

But let’s be clear. It is not “gerrymandering” — the drawing of lines for political purposes — that violates the federal constitution. The U.S. Supreme Court has held that redistricting for partisan purposes is acceptable — perhaps not ideal, but not unconstitutional according to the court — the reason being that a majority thought that the courts were incapable of measuring whether lines were too partisan to pass muster.

On the other hand, racial redistricting — that is, the drawing of lines where race is a predominant factor — is indeed unconstitutional. So we have Democrats alleging that the new Texas lines are a racial gerrymander (and the federal district court has so held in an 160-page decision) and Republicans alleging that the new California lines are a racial gerrymander, and that case is being litigated. The U.S. Supreme Court has stayed the district court’s ruling in Texas — so congressional races will be run on the unconstitutional lines there. Let’s see what happens in the California case, and in other states where new districts are being drawn.

I should note that, irrespective of the Supreme Court having washed their hands of challenges to partisan redistricting, such lines could be declared unconstitutional under a state’s constitution if explicitly forbidden. For example, New York’s state constitution bans redistricting that favors or disfavors a political party. As a result, if NY’s Independent Redistricting Commission or the legislature promulgates a partisan gerrymander, although there would be no remedy under the federal constitution, there would be one under the state constitution.

So, Mr. Gerry, we remember you. Not for the reasons you would like, but at least your name is on our lips. Many of your colleagues cannot say that.

I would be remiss, however, if I did not point out a supreme irony of Gerry’s handiwork. At the constitutional convention, he spoke against direct elections for president, U.S. senators and House members. His fear of demagoguery led him to conclude that state legislatures should choose House members just as, for so many years, they chose senators (until the 17th Amendment changed that in 1913). Although his view won the day in support of indirect election of the president and Senate, he did not persuade the convention to adopt indirect election for members of the House. Had he prevailed on this point, voters would have had no voice in the shape or size of their districts — thus there would not have been any complaints about gerrymanders.

In short, if the other Founders had agreed with Gerry and chose to have members of the House elected by state legislatures, we may never have heard of him.

Jerry Goldfeder is senior counsel at Cozen O’Connor, director of the Fordham University School of Law School Voting Rights and Democracy Project, chair of the American Bar Association’s Election Law Committee and author and editor of Goldfeder’s Modern Election Law (7th Edition (2025), www.nylp.com). The views expressed here are his own.