BY RICHARD E. GREENE, MD & PERRY N. HALKITIS, PhD, MS, MPH | In the past few years, we have experienced a revolution in the prevention of HIV. Gone are the days when approaches based on changing behavior were the only options. Biomedical technologies have provided us another set of tools in the arsenal to fight AIDS.

Robust scientific evidence has demonstrated that individuals at high risk for contracting HIV can now significantly reduce their risk of contracting the virus if they take a pill a day for the duration of the time that they are high risk. Slowly but surely this strategy, called Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP), is being adopted by healthcare workers as something to offer people who are at risk. In fact, it is one of the key components of the New York State Plan to End AIDS.

We call it a revolution, because it moves us forward in how we think and talk about HIV prevention, both between providers and patients and between sex partners (whether long-term, casual, or just potential). It moves us away from sex-negative messages and removes a great deal of fear many high-risk folks had about contracting HIV through sex. PrEP offers us many opportunities in the way we think and talk about HIV prevention, and counters the often sex-negative behavioral strategies.

To date, one drug, Truvada (a combination pill containing two medications, tenofovir and emtricitabine), is approved for PrEP, but others are on the way, as are injectable medications that would remove the burden of taking a pill every day — a reality that many HIV-positive people, of course, live with.

But PrEP is not the only innovation we have at our disposal. Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP) is akin to the morning-after pill used to prevent pregnancy — but for HIV. Many young people know about PEP. In fact, as part of the ongoing P18 Cohort Study at NYU’s Center for Health Identity Behavior and Prevention Studies (CHIBPS), we have surveyed 460 young men and transgender women ages 22 and 23, and 74 percent said they had heard of PEP. But only 8 percent have ever used it. (A similar proportion has heard about PrEP and only 7 percent reported ever using it.)

Why haven’t more people used PEP? PEP should be started within 36 hours of HIV exposure, so it is usually dispensed in hospital emergency rooms or urgent care centers. People are often given a “starter pack” of the meds and then asked to follow up with an outpatient primary care provider. The problem is, providers who work in the ER or the urgent care center generally haven’t seen the person before the high-risk encounter. To make matters worse, many primary care providers don’t prescribe PEP with any regularity. This prevention approach, then, is often lost in the mix of available strategies. In our study, of those who used PEP, only a third were prescribed in an ER.

PEP is not a new idea. Since 1996, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has recommended the use of PEP to treat health care providers who may have been exposed with needle sticks from HIV-infected patients. (In fact, sometimes the term nPEP — for non-occupational post exposure prophylaxis — is used to differentiate PEP used by health care professionals who experience an occupational exposure from that used by people who have sexual exposure to HIV.)

How does PEP work? It is meant to be used after sex, and getting the first pills within the 36 hours after a risk exposure is critical. These high-risk exposures include having condomless sex as a receptive partner with someone who is living with untreated HIV. PEP works by getting medication — in fact, a combination of three anti-HIV medications — into the blood and body to block the uptake of HIV before it can take hold in your system and result in infection. This is why timing is essential. PEP can sometimes be effective if initiated as long as 72 hours after the encounter, but the sooner the better. After the 72-hour mark, the pills are not likely to be effective.

Unlike PrEP, which is only one pill, PEP often is composed of a combination of pills. A variety of antiviral pills combinations are used as PEP, although Truvada and Isentress (raltegravir) are commonly prescribed. The medications are meant to be taken for 30 days following the exposure, and it is important to take the pills regularly. It is also helpful to know any antivirals the HIV-positive sex partner with whom you had a high-risk exposure is taking in case that person’s virus has developed resistance to the meds you are prescribed. You should also disclose whether you are on Truvada as PrEP.

It is also essential to be honest when being evaluated for PEP about what actually happened during sex, even though some people feel uncomfortable disclosing those sorts of intimate details.

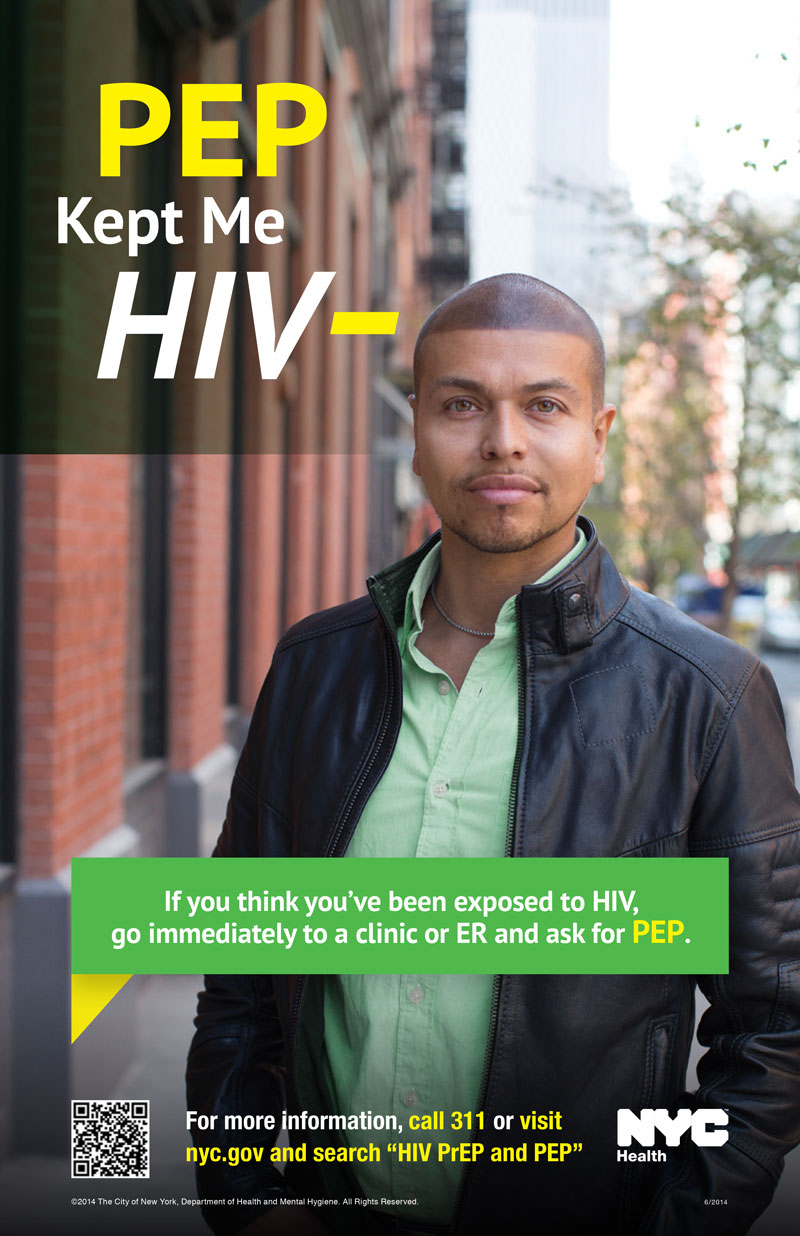

Perhaps the most important things to know about PEP are that it exists, it is effective, and how and when to get it. If you think you may have been exposed to HIV, go to an ER or urgent care center (or your primary care provider, but only if they are available right away), and get started quickly. You will have a rapid HIV test to make sure you are negative when initiating the treatment and a screen for STDs and kidney and liver function.

If you are unsure of whether you need PEP, it is always a good idea to be evaluated. Even if you start PEP and come to the decision with your primary health care provider that the encounter was not high-risk (in the case where the partner gets re-tested and is negative, for instance), you can stop the treatment. Once the 72 hours has passed, though, it will be too late to change your mind and decide to begin the PEP.

Anyone who wants more information on PEP or PrEP can go to the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene website, which has a wealth of information for patients and health care providers (at nyc.gov/html/doh/html/living/prep-pep.shtml).

Richard E. Greene is assistant professor of medicine and the medical director of the Center for Health, Identity, Behavior & Prevention Studies at New York University. Perry N. Halkitis is professor of applied psychology, global public health, and medicine and the director of CHIBPS. Anyone interested in participating in CHIBPS studies or learning more about the research it carries out can visit chibps.org. Follow Halkitis on Twitter @DrPNHalkitis or visit perrynhalkitis.com.