By Julie Shapiro

Members of the Landmarks Preservation Commission gave little hint of their reaction Tuesday after they heard extensive testimony on General Growth Properties’ plan for the Seaport.

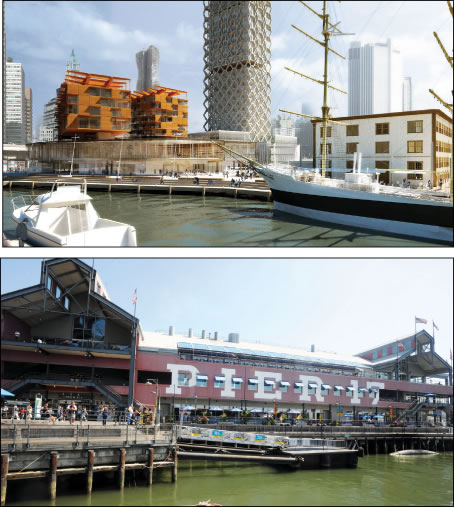

The three-hour hearing was the first stage of government approval for the mega-project and dealt only with the portion that lies within the South Street Seaport Historic District. Within the district, General Growth wants to demolish the Pier 17 mall, move the historic Tin Building from the pier’s base to its tip and build retail shops and a boutique hotel on the pier. On Tuesday, General Growth provided new details on all three of those projects.

Just outside of the historic district, General Growth also hopes to build a 500-foot condo and hotel tower on the site of the New Market building, but the Landmarks Preservation Commission will not review that project.

General Growth will return to the L.P.C. later this fall to answer questions and get feedback, though a date has not yet been set. Many assume L.P.C. will ultimately approve the project since the mayor’s office has already praised it, but the commission could ask for substantial changes to the design.

The commissioners, who are appointed by the mayor, asked only a few clarifying questions during General Growth’s hour-and-a-half presentation, and then they immediately opened the floor to public comment. Nine people spoke in favor of the plan and 11 people spoke against it. Supporters included the Downtown Alliance, New York Water Taxi, several historians and the American Institute of Architects.

A letter from the A.I.A.’s president and executive director called the new “distinctly modern buildings” on Pier 17 a vast improvement over the current “unremarkable mall architecture.”

J.C. Chmiel, a Seaport resident who owns Klatch cafe with his wife, also supports the plan.

“The Tin Building and New Market building always looked like mistakes, dark and dank under the F.D.R.,” Chmiel said.

General Growth donated space for a teen entrepreneurship program Chmiel ran over the summer, which shows the company’s commitment to the community, he said.

As for concerns that the 42-story tower will block people’s views, Chmiel asked, compared to what? Southbridge Towers and 1 Seaport Plaza block other people’s views, “And I don’t find them particularly attractive,” Chmiel said.

Opponents of the plan included the Municipal Art Society, New York Landmarks Conservancy, the National Maritime Historical Society and the Historic Districts Council.

Simeon Bankoff, director of the H.D.C., called the design of the planned retail buildings and boutique hotel “shockingly new” and said they would not age well.

“In a district of straightforward, practical buildings, whimsy does not fit,” Bankoff said.

Jean Grillo, a public member of Community Board 1, likened the design to Atlantic City.

“No school or promised public space will make up for what is forever lost,” she said. General Growth has offered to include community space for a school in the Fulton Market building as an amenity.

At a recent C.B. 1 meeting, board member Joe Lerner quoted the Bible to make a similar point: “A gift doth blind the eyes of the wise.”

Community Board 1 has not yet passed a resolution on G.G.P.’s proposal. The L.P.C. agreed to consider C.B. 1’s opinion as long as the board submits it within the next two weeks. C.B. 1 plans to hear more public comment on the project next Tuesday and then write a resolution. Board members’ views range between outright opposition, qualified opposition and support.

The commissioners remained largely silent throughout the hearing. Several left as it stretched into dinnertime, but those who remained took notes as members of the public spoke.

Tin Building To create pathways through the project and add open space, General Growth wants to dismantle the 1907 Tin Building and rebuild it on the end of Pier 17. The $70-million restoration is one of the most complicated pieces of the project and drew much opposition on Tuesday.

The Tin Building is currently sandwiched between the F.D.R. Dr. and Pier 17 mall, giving it a very different context than it once had when it towered over South St. with the East River directly at its back.

“The historic context was water and market, and all of that has been obliterated by 20th-century construction,” said Elise Quasebarth, a principal at Higgins Quasebarth & Partners who is working for G.G.P. “It’s completely hemmed in.”

While construction destroyed the three-story building’s historic context, a 1995 fire destroyed much of the historic fabric of the building itself.

Richard Pieper, director of preservation at Jan Hird Pokorny Associates, which restored the historic Schermerhorn Row buildings in the Seaport, said he had a difficult time finding the few pieces of the building that are worth preserving for the move General Growth plans. The fire destroyed the building’s windows and burned the entire third floor, along with much of the exterior. Afterwards, the city replaced the cornice and pediments with fiberglass replicas and encased the building in new siding.

All Pieper will be able to salvage from the front of the building is several window frames and portions of metal pilasters. But at the back of the building, he got lucky. Behind some bulky refrigerator enclosures that were added in the middle of the 20th century, a 3-foot stretch of the original exterior remains. Pieper calls the area a time capsule, and he said it would give him a wealth of information for the restoration, including the original paint colors.

The name of the Tin Building now has a historically important ring, but Pieper thinks that the nickname was actually a pejorative one, referencing the low-quality sheet metal composing the building. Usually preservationists would replicate the exterior features in a stronger metal, but since so little of the original building remains, Pieper plans to incorporate all the pieces he can save into the new building.

Those who object to moving the Tin Building say that stranding it out on the end of Pier 17, farther from the historic district, is not putting it into context. Since little of the original building is left, they think that at the very least General Growth should leave the building where it is.

General Growth can still build its tower without moving the Tin Building, but the project would not contain as much open space.

Pier 17 General Growth devoted very little of its presentation to the demolition of the 1984 Pier 17 mall, but during the public session several people fought to preserve it.

“That was quite surprising,” Michael McNaughton, vice president of G.G.P.’s northeast region, said after the hearing. “They want to preserve a mall on a pier.”

It isn’t so much the mall use people are keen on preserving as architect Benjamin C. Thompson’s design.

“Thompson is an incredibly important American architect,” said Michael Gotkin, from the Modern Architecture Working Group of New York City. Thompson is known for festival marketplace designs, and the American Institute of Architects guide calls the Pier 17 mall “gigantic, playful, adroitly detailed…an instant urban landmark.” The A.I.A., however, does not object to demolishing it.

Bankoff, from the Historic Districts Council, wondered in his testimony if future New Yorkers would regret the building’s loss. He wants to see the mall building preserved for cultural uses, restaurants and community-friendly retail.

New Buildings Once General Growth demolishes the Pier 17 mall and moves the Tin Building, the company plans to build a series of low-rise retail buildings on the pier, topped by a boutique hotel. The height of the new buildings on the pier varies, up to the 120 feet allowed within the historic district.

The project’s lead architect, Gregg Pasquarelli, principal of SHoP, plans to carve up the mass of the new buildings to allow for pedestrian circulation and sightlines to the Brooklyn Bridge. As he described how many tourists now arrive at Pier 17 and are unable to see the bridge, one Landmarks commissioner nodded in agreement.

Pasquarelli then introduced the designs of the new retail and boutique hotel buildings, saying he wanted to strike a balance between all of them having the same design and looking like pieces of an oppressive mega-project, and all of them being very different and looking like a disjointed pastiche.

The rust-colored boutique hotel, the tallest structure on Pier 17, will hang suspended by cables, an idea based on docks and shipyards. The boutique hotel is broken into two masses, with skywalks connecting them, evoking bridges over water. Wave-patterned wooden screens will wrap portions of the retail buildings beneath the hotel, while a series of pavilions beneath the F.D.R. Dr. will have a more industrial metal-and-glass design. A final pavilion on the pier at the base of Fulton St. will have a silvery skin based on sails and fish scales.

The commissioners asked several questions about the programming and density of the pavilions beneath the F.D.R. Dr., but they did not appear to oppose them. Pasquarelli is also one of the lead architects on the city’s Lower Manhattan East River waterfront plan, which includes similar F.D.R. pavilions nearby.

Open space All of the paths through and around Pier 17 will lead to a 40,000-square-foot plaza in the pier’s center. A small grove of trees will offer shade on the north side, but much of the plaza will be open to the sky, said James Corner, a principal at Field Operations who is planning the pier’s open space. In the summer, a series of small fountains based on pier piles will dot the center of the plaza, with seating among them. With the fountains off and the tables and chairs moved, the plaza could host “a flower market, a fruit market, or even a fish market,” Corner said. In the winter, the space could display ice art or support an ice-skating rink, he said. [See related article, Page 17]

A large net-like sculpture will dominate the eastern portion of the plaza, touching down to the ground and soaring upward like an enormous scalloped band shell. Corner hopes the structure will draw people farther out onto the pier to the Tin Building at the tip.

Though recent visitors to Pier 17 may imagine it has always been made of wood, the pier was actually once topped with stone. Corner plans to return to that history by paving nearly all of Pier 17 in granite cobblestone. Since people like the warmth and comfort of wood, he will use it around the perimeter of the pier and on the steps leading down to the water for public seating.

New Market site The 42-story tower General Growth hopes to build was not on the table during Tuesday’s hearing because it sits outside the historic district, but that didn’t stop the public from commenting on it. General Growth plans to demolish the 1939 New Market building on a platform just north of Pier 17 and build the tower in its place. The height limit on platforms is 350 feet, but General Growth will ask for a special permit to build the tower 500 feet tall.

Some residents and historic preservation groups have recently seized on a new idea to block the tower plans: They want to extend the historic district to include the New Market building, which would make it all but impossible for G.G.P. to demolish it.

“The building’s iconic history is undeniable,” said Bankoff, from the Historic Districts Council.

The city had two opportunities to include the New Market building in the South Street Seaport Historic District: in 1977, when the district was created, and in 1989, when the district was expanded. Both times, the city left the building out, likely because “It’s not the same type of building for which the district was created,” said Lisi de Bourbon, spokesperson for the Landmarks Preservation Commission.

Those who want to preserve the New Market building point to the state’s inclusion of the building in its version of the historic district in 1978. However, the state did not consider the building a contributing member of the historic district, and in any case, the state designation does not prevent General Growth from demolishing it. The state’s 1978 report calls the New Market building “of rather uninspired and simple design.” Since the elevated F.D.R. Dr. blocks much of the building from public view, “it is somewhat less obtrusive than it would otherwise be.”

The Municipal Art Society thinks preservation trends have changed since 1978. Melissa Baldock, a historic preservation fellow at M.A.S, pointed to the 2003 landmarking of Gansevoort Market buildings as an example of saving mid-century market buildings. The M.A.S. hopes to convince both the city and state that the onetime fish market building should be preserved.

“They’re very utilitarian,” Baldock said of market buildings. “They’re not architectural gems, but they’re culturally important.”

Zoning The idea of a 500-foot waterfront tower is particularly galling to the residents who spent years fighting for the rezoning of the historic Seaport. In 2003, the city agreed to limit new buildings to 120 feet on 10 blocks of the historic district bounded by Fulton, Pearl, Dover and South Sts. The catalyst for the rezoning was a parking lot at 250 Water St., where Milstein Properties wanted to build a high-rise. The rezoning prevents Milstein from building higher than 120 feet but does nothing to stop General Growth from building far higher on the other side of South St.

“We worked so hard to limit the height of development in the historic district and to preserve the small scale,” recalled Gary Fagin, who fought for the rezoning as part of Community Board 1 and the Seaport Community Coalition. “A tower there would be huge obstruction to that.”

Fagin said the New Market site was left out of the rezoning because he already had enough trouble getting the 10 upland blocks approved. Including the unlandmarked New Market building would have raised a slew of waterfront zoning issues, and the city was not in favor of it, he said.

“It was obvious to us that the New Market building was going to be key to the financial viability of any redevelopment of the Seaport,” Fagin said.

Several other people involved with the rezoning remember things differently.

“I don’t think we were aware that site was left out,” said Marc Donnenfeld, former chairperson of C.B. 1’s Seaport/Civic Center Committee. “I don’t think anyone was aware…. Had we known that something might have been left out, we definitely would have included it.”

When the City Planning Commission changed the zoning in the uplands, they were trying to protect the Seaport from out-of-context development.

“The historic Seaport area simply is not an appropriate place for high density development,” the commission wrote in 2003. “In fact, the commission firmly believes that the Seaport will make a more valuable contribution to the revitalization of Lower Manhattan if its existing character is enhanced, not contradicted, by new development.”

Julie@DowntownExpress.com