BY DAVID NOH | The one emotion that you come away with from the David Hockney retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art — and, indeed, that you experience all through your viewing of it — is joy. He is living proof that great art needn’t be dark, tortured, or full of angst.

Hockney comes instead from blessedly more accessible schools of art, like those of Boucher, Fragonard, and Toulouse-Lautrec, where, largely, pleasure and its depiction represent the project at hand — in his case, in images of Southern California, portraits of friends, and even his earliest work, in which he staked out a personality and unique style that have remained remarkably consistent for the last 60 years. It’s a marvelous, truly inspiriting show, especially when you consider that the artist is now 80 and still paints every day, better than ever, his mastery over his trademark, vivid Fauvist palette and uniquely skewed perspective displaying a now magisterial confidence and ageless brio.

For me, the most striking discovery of this show, comprising some 60 paintings, as well as drawings and photocollages, curated by Ian Alteveer, are those early works, from the 1960s, which came well before, but look like nothing so much as the vividly urgent, graffiti-strewn canvases of the East Village scene in the 1980s. Although cleaner and somewhat more Brit-decorous, they particularly remind one of Jean-Michel Basquiat, who surely must have had a hard look at these quite brilliant mixed media, sometimes collaged assemblages, replete with commercial product imagery of Colgate toothpaste, Alka Seltzer, and Typhoo tea, as well as highly personal, scrawled graffiti. But, where Basquiat’s on-canvas scribblings dealt with race and oblique self-empowerment, Hockney’s wording shows him to be nothing short of an absolute pioneering gay activist, sneaking subversive messages of queerness onto his canvases, like little gay affirmations (“Come on, David, admit it.” “Ring me anytime at home”).

Artist David Hockney gets a dazzling retrospective at the Met

Hockney’s very first important artistic statement was this youthfully energized proclamation of his homosexuality in the early 1960s, a time when that was a punishable offense in the eyes of the law. Existing in a sexually free utopia (where he’s probably always lived, at least in his own fertile mind), there’s a bracing and beautifully forthright innocence — as well as sly knowingness — to these bold little fillips in boldly rendered paintings like “Cha Cha Cha,” which celebrates that life-enhancing staple of gay life, dancing in a club, or “We Two Boys Together Clinging,” which was inspired by a Walt Whitman poem, as well as the headline of a news story about a hiking accident, “Two Boys Cling to Cliff All Night.”

The mystery, if any, in Hockney is how on earth did this working class boy from the northern boondocks of Britain grow up with such total self-acceptance and bravado and go on to mature with such a seemingly neurosis-free constitution. Born in the seaside town of Bradford in 1937, the fourth of five children, Hockney’s father instilled in him a pride of self, to never be ashamed of his Yorkshire roots or thick accent, and to always stand up for his rights. His beloved mother was vegetarian and a staunch Methodist. Dad — a conscientious objector in World War II — was a humble clerk in an accountant’s office but had interests in painting and invention. Hockney remembered the smell of the paint of the sunrises with which his dad had decorated the doors of their home, saying that instilled the desire to become a painter in him.

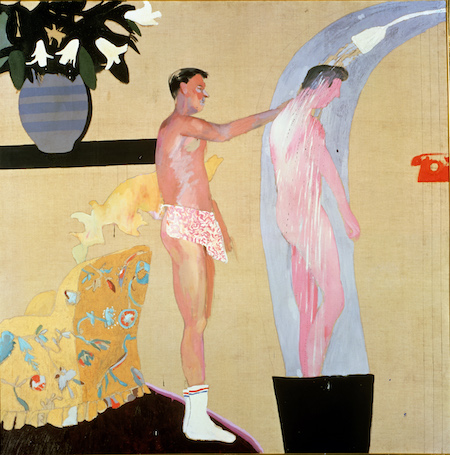

His innate drawing skill from early youth brought him to the Royal College of Art in London, where his talent was evident, but he nearly didn’t graduate due to his refusal to write a final essay, feeling that his artwork should be all that was required of him. The school bent in favor of his gifts and already burgeoning recognition and gave him a diploma. He had his first one-man show in 1963, age 26, and, in 1966, his painting “Peter Getting Out of Nick’s Pool,” won the John Moores Painting Prize at the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool.

“Peter” was Peter Schlesinger, an American art student he met while teaching at UCLA, who became his lover and most famous muse, for it is he who figures most prominently in Hockney’s signature, sometimes homoerotic California pool studies, often in the nude. By 1964, Hockney had fallen deeply in love with the sunny, open ambiance and gorgeous, youthful populace of Los Angeles, such a far cry from his own gray, chilly roots and moved there to live. The real mark of any great artist is their ability to change the way we see things and, certainly, Hockney’s wondrously stylized vision of his adopted home — with its ubiquitous palm trees, swimming pools, and sunbaked inhabitants — happens to still be most cultured people’s idea of the City of Angels.

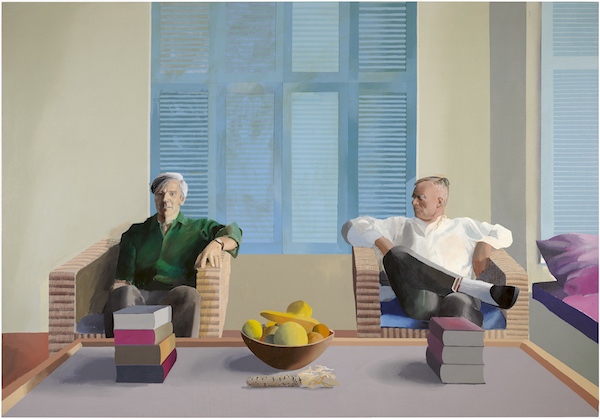

Hockney’s work paid no mind to art trends, like minimalism and various forms of abstraction, and was always supremely presentational, opening a veritable visual diary of his long and fruitful life. Also figuring prominently in the show are Hockney’s marveloulsy witty portraits of certain flamboyant personalities, who were mostly his good friends — Warhol, Cecil Beaton (not at all happy wth his likeness, he said, “How could he like me if he sees me thusly?”), Henry Geldzahler, W.H. Auden, the lovers Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy (who amusingly seem to be in some kind of a snit). His 1970 life-sized masterpiece, featuring Ossie Clark, the brilliant fashion designer who would be tragically killed in 1996 by a crazy male lover, and his wife at the time, lovely Celia Birtwell, one of the most visited paintings in Britain, is on loan from the Tate Gallery and, like all of the famous and even not so renowned works on display, it fairly leaps off the wall at you brilliantly, in a way a reproduction simply cannot.

Hockney’s latest, brilliantly colored work of his idyllic Hollywood Hills studio and sylvan surroundings addresses what he refers to as “reverse perspective,” inspired by his findings of the writings of Russian mathematician and art historian Pavel Florensky, who made a case for art that eschewed traditional perspective, in favor of the skewed layouts of ancient Russian icons as well as Egyptian and Asian works. Conceptually, the new work is something of a continuation of his so-called “joiners,” the paintings of winding Los Angeles roads and fractured interiors that he achieved through the use of multi-layering Polaroid photos he’d taken of a particular view.

Those Polaroids were but one step in Hockney’s long and continuing exployment of modern technology in his work, all of which appear in the show: In 1985, Hockney used the Quantel Paintbox, a computer program that allowed him to sketch directly onto the screen, and lately he has been into art applications on his iPhone and iPad.

Hockney, who refused a knighthood in 1990, smokes a pack a of cigarettes a day, and holds a California medical marijuana verification card, enabling him to legally buy weed, turned 80 on July 9, and to see him today is something of a shock. One rather envisions him as his preternaturally youthful, eminently iconic self, healthy and stocky, with that shock of bleached blonde hair — his touchstone reference to his beloved Southern California — and round tortoise shell specs. He now has gone gray, uses hearing aids, and is stooped in his posture, but his energy certainly seems undiminished.

According to a New York Times interview, the artist has someone in his life whom he describes as “my faithful companion of 15 years,” Jean-Pierre Gonçalves de Lima. Asked if they intended to marry, Hockney said no, adding “Marriage is about property. When you get divorced, you know it’s about property.”

Beaton, who was one of his first benefactors, buying a painting of his when he was an art student for 40 pounds — which enabled Hockney to take his first trip to New York — I think definitively described him: “We could not be further apart as human beings, and yet I find myself at ease with him and stimulated by his enthusiasm. For he has the golden quality of being able to enjoy life… Life is a delightful wonderland for him.”

DAVID HOCKNEY | Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 Fifth Ave. at E. 82nd St. | Through Feb. 25: Sun.-Thu., 10 a.m.-5:30 p.m.; Fri.-Sat., 10 a.m.-9 p.m. | $25; $17 for seniors; $12 for students | metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2017/david-hockney