Five decades removed from the decree that brought to an end the horrors of the Willowbrook State School on Staten Island, and the war to ensure the rights of all developmentally disabled Americans to dignified care rages on.

Without question, we are in a far better place than we were 50 years ago when parents like me were desperate to move their children out of Willowbrook, a house of horrors where people who could not take care of themselves were left to wallow in neglect and filth.

Yet here we are, 50 years later, and while Willowbrook is long gone, we are doomed to repeat its sordid history if we do not remember the road that got us to this point.

For me, this fight is personal. My husband, Murray, and I brought our Lara to Willowbrook, where she was admitted to the campus’ baby ward — the only facility in the region that could offer physical and occupational therapy five days a week. She was developmentally a three-month-old who needed total care.

I visited Lara every weekend. I remember her being in the first bed as you entered the ward, but most of our visits took place in the waiting room. When I began protesting, I pushed my way to the ward and realized that they had moved Lara’s bed to the back of the ward in retaliation for my advocacy.

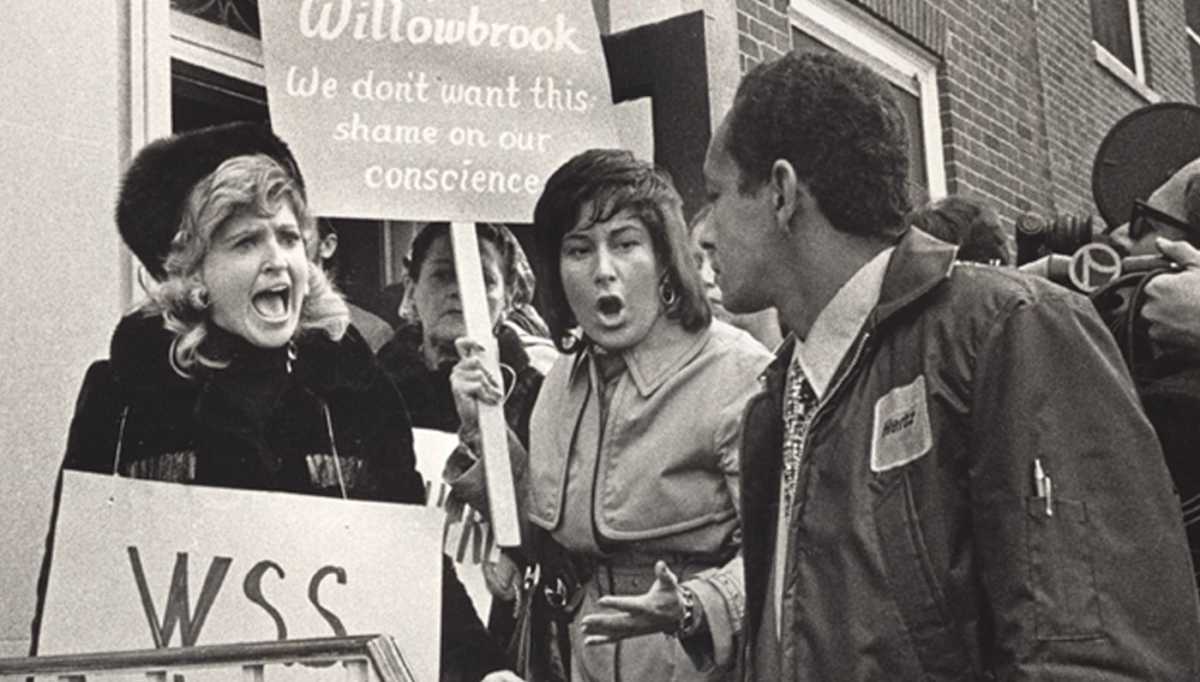

Murray and I pickedeted with other parents, seeking first the return of the cut funds from New York State to boost the quality of care at Willowbrook. Under then-Gov. Nelson Rockefeller, funding for institutional care had been repeatedly cut year after year.

But we soon realized that funding alone was not enough; the problem was Willowbrook itself, which finally became public thanks to the intrepid reporting of a young journalist named Geraldo Rivera in 1972.

Dr. Michael Wilkins at Willowbrook snuck Rivera and a cameraman for WABC-TV into one of the adult buildings on campus and documented the terrible blight and conditions people lived in each day.

His description of the ward — where patients were left to their own devices, some naked, others covered in their own feces — has stuck with me for decades since: “This is what it looked like, this is what it sounded like, but how can I tell you about the way it smelled? It smelled of filth, it smelled of disease, and it smelled of death.”

How did it get so bad at Willowbrook? There were roughly 50 residents, each severely developmentally disabled, for every attendant on staff. Years of funding cuts and general apathy from the public created an environment of disorder, dysfunction and maltreatment that no person should ever experience.

We were determined to stop this. Murray and I led a class-action lawsuit in federal court seeking intervention. The exposé of Willowbrook convinced parents who initially declined to participate in the lawsuit to change their minds and sign on as plaintiffs. Their action made it possible for the Willowbrook Consent Decree that was signed into law in 1975. It ensured the right of every developmentally disabled American to quality, dignified care in small settings.

Yet the decree alone was not enough. No one could leave Willowbrook without having a day program and a group home in place, and we had to fight the government tooth and nail to ensure proper funding. We also fought community resistance to the group homes, being sued by the Little Neck Civic Association, which tried to stop us from opening the first group home for children from Willowbrook in New York State. We won that lawsuit, too.

Incredibly, even with the horrors of Willowbrook still fresh in the public’s minds, there were elected officials who still tried to deny us the proper resources to care for our children and adults in need.

In fact, this fight, which I call the “Willowbrook Wars,” continues five decades later on a different front.

Many group homes caring for developmentally disabled New Yorkers are operated by nonprofits. Because of a pay disparity, these organizations are having a tough time hiring and retaining direct service professionals (DSPs) to work one-on-one with each individual in the homes.

State-run group homes pay their unionized DSPs $25 per hour; on the other hand, nonprofit groups pay their nonunionized DSPs $17 per hour, only a few cents above the hourly minimum wage. What incentive does a nonunionized DSP at a nonprofit have to stay on the job for the incredibly hard work they do when they could make the same money doing something less intensive?

If this does not change, we’re going to lose great people who provide incredible care to people who need it. The state must step up and give nonprofits the funding needed to pay competitive wages, which will allow them to recruit and retain the best talent and provide the best care.

Failure is not an option for nonprofits and, more importantly, for the individuals in their care. The pay situation is so unsustainable that it risks undoing all of the progress made in the 50 years since Willowbrook and resurrecting the horrors upon other families and individuals who deserve the best treatment they can get.

In memory of my daughter Lara and all those who fought so hard to win the Willowbrook Wars, we must not let that happen — never again!

Victoria Schneps is owner and president of Schneps Media.