[/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

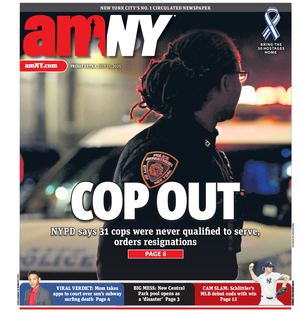

- An exhibit currently on display at the African Burial Ground National Monument shows how slaves in New York City lived and died.

BY TERESE LOEB KREUZER | Lower Manhattan has a special claim to prominence during February’s commemorations of black history. It is the site of one of the largest African-American cemeteries in the United States.

Late in 1991, workers began to excavate the foundation for a 30-story federal office building at 290 Broadway. In May, they came on the bones – hundreds of human remains, all that was left of the thousands of enslaved African men, women and children who had helped build New York City. Slavery was not completely outlawed in New York State until 1827. In the colonial period, slaves comprised around one-fourth of New York City’s labor force. They were consigned to swampy land outside the city’s walls when they died. In many cases, their bones were scarred and deformed by the harsh and short lives they had led.

What turned up under the backhoes should not have been a surprise. A map of New York City from 1755 now in the Library of Congress showed what was called the “Negros Buriel Ground” at that very spot.

The 6.6 acre cemetery was used from the 1640s to 1794, when a 110-foot-tall promontory called Bayard’s Mountain two blocks to the north, near where Columbus Park is now, was leveled off and the earth dumped on the graves to create a flat surface on which to build houses for the growing city. The bones of around 15,000 people were now 24 feet below the surface. No one found them again for almost two centuries.

After the first discoveries, workers continued to construct the office building. Four hundred and nineteen skeletal remains were sent to Lehman College in the Bronx for storage.

“It was a major fight on the part of the black community to keep them from continuing to build,” said Denise Walden Greene, a staff analyst and administrator with New York City’s Department of Children’s Services, who was visiting what is now the African Burial Ground National Monument.

African descendants, clergy, politicians, scientists, historians and concerned citizens fought to preserve the site and honor the dead. In 1992, they staged a 24-hour vigil. Congress responded, decreeing that the building plans be altered to provide for a memorial. Subsequently, the remains were transferred to Howard University in Washington, D.C., where they were studied for eight years.

In October 2003, all of the remains were returned to Lower Manhattan and reburied in mahogany coffins carved in Ghana. On Feb. 27, 2006, a presidential proclamation designated the site as the African Burial Ground National Monument.

Today, the African Burial Ground memorial occupies three-quarters of an acre near Duane Street and Broadway with a visitors’ center in the building at 290 Broadway. The bodies are buried under seven mounds of grass on top of which people have left offerings of flowers, money and shells. Nearby are seven serviceberry trees. “They are guardians, so the building doesn’t disturb their rest,” said Sean Ghazala, a guide with the National Park Service, which now has jurisdiction over the site. He also explained that, “In the colonial period, when serviceberry trees bloomed in the spring, people knew that the ground had thawed enough that they could bury their dead.”

A granite monument near the burial mounds designed by Haitian-American architect Rodney Leon was dedicated in October 2007. It suggests the shape of a ship such as those that brought millions of Africans to the eastern seaboard of what is now the United States. In warm weather, it is surrounded by water. It leads to a circular space centered by a map that shows Africa, Europe and the New World and is surrounded by West African and Caribbean symbols of memory and protection. A West African symbol called a “sankofa” is prominently inscribed on the monument. It means “learn from the past to prepare for the future.”

The visitors’ center inside the building at 290 Broadway contains exhibits that show how New York City’s African slaves lived and died. One wall shows photographs of the bones. On the opposite wall is a photomural of the protesters who fought to preserve the cemetery as sacred ground. In between them are life-sized figures of a family mourning over simple pine boxes as they prepared to bury their dead.

The African Burial Ground National Monument Visitor Center is open Tuesdays through Saturdays from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. and closed on all federal holidays. The African Burial Ground National Monument Memorial is open daily from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. except for federal holidays.

During Black History Month, special programs have been scheduled. For more information, go to www.nps.gov/afbg.