Update, Thurs., Feb. 5, 6:45 p.m.: According to Jimmy McMillan, Adult Protective Services has been able to delay his eviction until Wed., Feb. 11.

BY ZACH WILLIAMS | East Village resident Jimmy McMillan had two days left, and one final legal tactic to deploy before a scheduled eviction from his St. Mark’s Place apartment on Feb. 5.

The 68-year-old combat veteran best known as the founder of the Rent Is Too Damn High Party — on whose line he ran for governor in 2010 — remained hopeful that Adult Protective Services would intervene in time to prevent the eviction. After years of battling his landlord in Housing Court about rent, keys and just exactly where his primary residence is located, this was his “last draw,” after he received the eviction notice on Jan. 15, he told The Villager in a Feb. 3 interview.

He described his current predicament as the latest mission in a life determined, first and foremost, by his service in the Vietnam War, for which he now receives full disability payments for post-traumatic stress disorder. He must “lead from the front,” given his stature as a landlord-fighting rabble-rouser, he added.

“I can’t tell you how to fight if I don’t know how to fight,” he said. “So right now, I got my boots on and I’m fighting my ass off to keep them from throwing me out.”

News of whether the effort to avoid eviction through Adult Protective Services was successful was not available as of press time.

Under a 2009 agreement with the landlord, Lisco, McMillan said, he sent rent payments to his landlord only to have them returned. A new key to his building was not provided per the agreement. He displayed photocopies of purported court documents to corroborate these claims.

What his landlord really wants, according to McMillan and his attorney, John De Maio, is to eject the activist from his rent-stabilized one-bedroom apartment in order to replace him with a new tenant at a higher rent. McMillan currently pays $872 per month, far below the prevailing rate in the hot East Village real estate market.

A Lisco representative could not be reached for comment by press time.

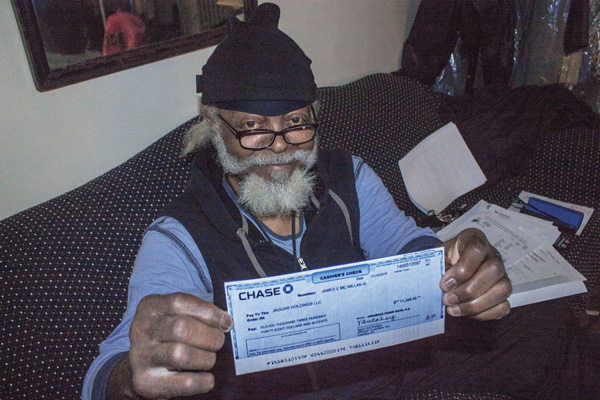

The landlord charges that McMillan owes $18,359, an amount the activist disputes. McMillan expressed willingness to pay a significant portion of that sum, and showed The Villager a cashier’s check in the amount of $11,348.48, dated Jan. 18. But Lisco has yet to accept that payment, as well as his future residency at the apartment on St. Mark’s Place near Avenue A.

Lisco has previously contended that McMillan’s primary residence was in Brooklyn, thus nullifying McMillan’s rent-stabilized status in Manhattan, McMillan explained on a well-worn sofa inside of the East Village apartment.

Keepsakes from his various political campaigns — he has run for office a half-dozen times — adorned the walls. The kitchen was dark and a pile of clothes lay in one corner of the living room of the bachelor pad near a mounted trio of antique saxophones. His Brooklyn apartment, on the other hand, was an office, said McMillan, who now lives alone in the East Village.

Amid his dossier of papers relating to his housing case was an unopened letter from federal court, in which he filed a lawsuit last week alleging that his landlord was extorting him. McMillan is seeking more than $1 million in damages.

He said he new that federal court did not have jurisdiction in his case, but that the legal maneuver was a response against his landlord.

“I knew it was going to be thrown out, but I had to make some noise,” he said.

His fight is important not only for securing his housing but also the greater cause of tenants’ rights throughout the city, McMillan said.

“I’m letting myself get evicted because I needed to let the people know this got to stop,” he said. “When the marshal comes through the door, I don’t know what time, but I’m going to be sitting right here.”

De Maio said in a telephone interview that the legal system might not come through for McMillan in time to prevent his eviction, despite his client’s lease, age, public service and willingness to pay outstanding rent.

“The idea that the system is not broad enough to help a man in this situation is despicable,” he said.