By HEATHER MURRAY

New York City zoning regulations currently allow chain stores to move in as of right and offer no protection to small businesses from rising rent, rising wholesale prices and a declining customer base.

That policy could change for the East Village if a community group’s plan to amend the city’s Zoning Resolution to prevent chains like Starbucks and CVS from displacing local businesses and altering the character of the neighborhood is successful.

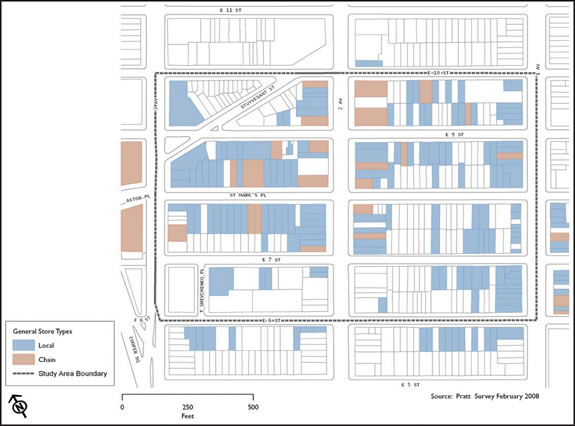

The East Village Community Coalition announced in January that it had enlisted Vicki Weiner, director of planning and preservation for the Pratt Center for Community Development, for recommendations on strategies to retain local businesses. This spring, Weiner led a class of graduate students who studied a sample area between E. Sixth and E. 10th Sts. and Third and First Aves., and issued a report. E.V.C.C. is exploring proposing zoning changes for retail in the area between E. 13th and Houston Sts. and between Third Ave. and the East River to restrict so-called “formula businesses”; these zoning changes would discourage large retailers from moving in either through size caps, permit requirements or outright bans.

Formula businesses typically include retail stores, restaurants and hotels that offer standardized services, operating methods, decor, uniforms and architecture, along the lines of Starbucks and McDonald’s, for example.

This initiative follows on the heels of another zoning change proposal recently pushed by E.V.C.C.: a 111-block rezoning plan that would cap building heights at eight stories in most areas of the East Village and parts of the Lower East Side and at 12 stories for Houston, Delancey and Chrystie Sts. and Avenue D. The rezoning plan, which was approved by Community Board 3 in May and will go into effect in a few months if approved by the City Council as part of the uniform land use review procedure, or ULURP, process, is bounded by essentially the same area as E.V.C.C.’s formula business restriction initiative: E. 13th St. to the north, Avenue D to the east, Grand and Delancey Sts. to the south and 100 feet east of Third Ave. and Bowery to the west.

Graduate student Elizabeth Solomon presented the students’ findings Thurs., June 12, at St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery on E. 10th St. Her presentation followed a screening of “Twilight Before Dawn,” a documentary by filmmaker Virginie-Alvine Perrette on preserving local retail, and preceded a discussion moderated by Weiner.

St. Mark’s Place ban

The most stringent recommendation of the report, “Retail Studies and Initiatives for the East Village,” is to ban formula retail, or chains, on St. Mark’s Place from Third Ave. to Avenue A. Existing chains would be grandfathered in, meaning they could remain. This recommendation is modeled after San Francisco, which is the largest U.S. city to restrict formula or chain businesses, banning them in two neighborhoods and regulating them almost everywhere else.

The Pratt report recommends that chain stores no longer be allowed to move into the East Village without restriction; chains would need to obtain a permit to bring in a formula business.

Under the recommendations, chains would be required to help out small businesses through a formula retail, or “big-box,” tax. The tax would go into a small business fund to provide grants to local businesses and would be graduated based on gross sales of the chain. The big-box tax is based on proposed legislation in Minnesota and Maine. The Minnesota tax would be imposed on a chain if its revenues are greater than $20 million, average employee wages plus benefits are less than $22,000 and one-fourth or more of its workers are part time.

The Pratt students are also proposing a commercial landlord tax credit for landlords who voluntarily provide commercial rent control for their tenants. The credit would increase over time.

The Pratt report also recommends transportation improvements, including a parking improvement district, residential parking permits, a bike-share program, widened sidewalks and a fare-free, cross-town bus route. Sunday street closings during the summer season should be encouraged, they say. The location of the street closings would be changed weekly. In addition, the Avenue A Greenmarket would be expanded.

The Pratt group suggested that E.V.C.C. expand its “Get Local” Web site, which showcases small business owners in the East Village. E.V.C.C. just recently produced its second annual “Get Local Guide” booklet.

Solomon indicated that “precedent already exists in New York City” for proposing regulations like these. The Little Italy Special Purpose District has bulk and use restrictions, and the Madison Ave. Special District imposes design guidelines for storefronts.

A retail market analysis indicated that the East Village is trending toward younger residents with greater median income and higher education. The analysis determined that, annually, residents could be spending $12,400 more per household of their disposable income locally.

The students recommend creation of a new administrative arm of Community Board 3, specifically a special review board to focus on formula retail permits. Seattle, for one, has a special review board that looks at store design guidelines, reviews permits and handles chains “giving back” to the community through funding-assistance programs.

Retail rent regulation

An audience member at the June 12 meeting asked why the Pratt graduate students hadn’t considered regulating rent, pointing out that imposing commercial rent control was discussed 20 years ago by the City Council but was never enacted.

In fact, a New York City law protecting commercial tenants from displacement due to rising rents was in place from 1946 to 1963. Then-City Councilmember Ruth Messinger and some colleagues attempted to resurrect the regulation in 1987, but it was defeated in the Council.

Weiner pointed out that the students’ report does touch on rent regulation, although the recommendation is to make it voluntary and provide a tax incentive for landowners who keep rent hikes manageable for their tenants.

“If we proposed a blanket application, that would be such a conversation killer,” she said.

Andrew Berman, executive director of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, asked if there have been any legal challenges to the formula retail laws in San Francisco and Seattle and whether they survived those challenges. Weiner replied that many of the laws enacted have been challenged, but all are still in place. Seven cities nationwide currently ban or cap restaurant chains and 12 ban or cap retail chains.

Berman asked why it took chains so long to break into New York City and what caused the floodgates to open. Weiner said she couldn’t point to one incident triggering the proliferation of chains, but said policy changes have helped bring in the chains. Chains have taken advantage of the Industrial and Commercial Incentive Program, a tax credit designed to help businesses, she said, noting, “Tax incentives have allowed them to flourish.”

It’s a fact that mom-and-pop stores are being replaced by chains citywide. Between 1990 and 2003, the city lost 447 neighborhood pharmacies and gained 434 chain pharmacies, as highlighted in the 2007 documentary film “Twilight Before Dawn.” Filmmaker Perrette captured the struggles facing small business owners, in many cases filming merchants and customers on the last day before businesses closed up shop.

Community can win

In the most triumphant clip in the 36-minute film, Perrette portrays a community’s successful fight to keep its neighborhood pharmacy from losing its lease. Bashir Suba, owner of Suba Pharmacy at 104th St. and Broadway, opened his store back in 1982. In May 2004, he received a notice from his landlord that he had to vacate the building by September of that year. More than 4,500 residents signed a petition asking the landlord to keep Suba at its location. They also called the bank that was ready to move in once Suba moved out, warning they would take their business elsewhere. They rallied outside the store, holding up signs saying “Save Our Pharmacy.” The landlord listened to the community and gave Suba a new eight-year lease.

Residents had galvanized around Suba once before, when a CVS moved into the area on the heels of a Rite Aid and two Duane Reades. A community group boycotted the CVS and it closed in 2002.

Perrette didn’t start out as a filmmaker. The former environmental and international boundary-disputes lawyer and Upper East Side native moved back to New York City after a decade-long hiatus in 1999 to discover that her favorite Upper East Side grocery store had disappeared. Deciding law wasn’t for her, and always having been interested in documentary filmmaking, she enrolled in a class at New York University in 2000. She chose as her class project the phenomenon of the vanishing local retail market. Six years and 70 hours of film later, “Twilight Before Dawn” was completed.

In addition to interviewing local merchants, she also spoke with local and national authorities on the role of small businesses in fostering community and preservation efforts. Some of her subjects she came across by happenstance. Dr. Peter Whybrow, director of the U.C.L.A. Neuropsychiatric Institute, was speaking on N.P.R. one day about “all these issues of community” when Perrette realized he’d be perfect to interview. She Googled him and asked whether he’d be interested in being interviewed for the film. He was, and in the film he describes local merchants as “social tethers” in their communities. He feels there is a correlation between the presence of locally owned shops — and the connections made between their employees and residents — and our health.

Suddenly, change happens

The title “Twilight Before Dawn” comes from a John Barth quote that Perrette first saw hanging up in the office of a lawyer she worked with in Boston. She was so moved by the quote that she posted it on her refrigerator. One day she realized “this is the story of the film,” An abbreviated version of the quote, from “The End of the Road,” reads: “It is possible to watch the sky from morning to midnight…without ever being able to put your finger on the precise point where a qualitative change takes place; no one can say, ‘It is exactly here that twilight becomes night.’ … [S]uddenly one realizes the change has already been made, is already history, and one rides along then on the sense of an inevitability, a too-lateness…which for one reason or another, [one] does not see fit to question.”

A too-lateness is what she felt in 2002 while filming the closing day at Michael’s Barber Shop, where she had received her very first haircut decades earlier.

Or at M&E Hardware in East Harlem in 2005, when Manny Schwarz, his son Eric and family closed the shop after more than 52 years in business. Perrette dedicated the film to Manny Schwarz, who died in 2007.

“The family kind of embraced the project,” she said. “I felt welcomed by them. They invited me to their house in Queens to go through old photos with them… . Manny really had this hope for small business owners that he expressed very clearly.”

She struggled to continue the project at a film class in Maine she took only two weeks after Sept. 11, 2001, asking herself, “In the big picture, does this really matter anymore?” She later realized that the downturn in business after 9/11 made her film “even more important,” not less.

Perrette is concentrating on publicizing her film mainly through word of mouth. She has taken an activist role in seeking change for small businesses, reaching out to New York City councilmembers and local organizations.

“The film is meant to really speak to each individual and communities, and say we really have the power to do something about this,” Perrette said.

When asked by Pratt’s Weiner what she would say to those who dismiss her film as focusing too much on nostalgia, Perrette said, “I did not want the film to be about nostalgia. There are so many other reasons to protect these businesses. … It’s very obvious that toothpaste is cheaper at Duane Reade than a neighborhood store, but the idea is that other calculations have to be taken into account.” She said it’s estimated that when $1 is spent at a local business, 15 cents leaves the community, whereas with a chain, 84 cents doesn’t benefit the neighborhood.