By Sharon Hartwick

“Ours to Fight For” is the first exhibition to take an in-depth look at the role Jewish men and women played on and off the battlefield during World War II. It’s a fitting choice to celebrate the opening of the new Robert M. Morgenthau Wing at the Museum of Jewish Heritage. The 82,000 square foot addition to the six-year old museum includes a gallery with dramatic views of New York harbor and the Statue of Liberty.

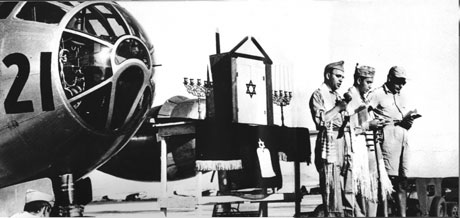

Approximately 500,000 Jews served in all branches of the U.S. armed forces and 52,000 were decorated for bravery. And many of their personal stories are told here through personal quotes, letters, photos, video testimony and more than 400 artifacts.

“As a Jew, it was Hitler and me. That’s the way I pictured the war,” read a quote from a soldier serving in the U.S. Army Air Force.

Visitors can also sit in on a WWII-era “Home Front Theater” and view archival footage of American soldiers entering the concentration camps at the end of the war and encountering the reality of the Holocaust.

As part of this comprehensive exhibit, the Museum has also sponsored a number of special events.

On December 10, a panel discussion, billed as a “conversation to explore the ethics of reporting from the battlefields” was held with journalists who have served on the frontlines.

“Direct from the Trenches: War Journalists from WWII to Iraq” was moderated by Samuel Freedman, Associate Dean of the Columbia School of Journalism and author of “Jew vs. Jew : The Struggle for the Soul of American Jewry.”

Referring to the “extraordinary exhibit,” Freedman said the discussion was an opportunity to expand on the experiences of those who fight in wars to those who report or write about them.

The panelists included Walter Rosenbloom, a photojournalist whose career spanned 50 years. A U. S. Army combat photographer during World War II, he landed at Normandy with the invasion and recorded the first images of Dachau.

Michael Norman, a professor at the N.Y.U. School of Journalism and a former Marine, is the author of “These Good Men, Friendships Forged From War,” a memoir of his experiences in the Vietnam War. He’s now working on a book about the Bhutan death march.

And Josh Friedman, professor and director of the international department at Columbia School of Journalism, is a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter who has covered conflicts in the Balkans, Beirut, Israel and Africa.

Sam Freedman opened the discussion by asking if there’s any way that a Jew experiences war as a combatant or chronicler that’s different from how others experience it, including the effect of religious teachings.

Josh Friedman responded that he was most influenced by his grandmother and her stories of growing up in Poland and relating what life was like for Jews in Eastern Europe.

The Holocaust, he said, was such a “searing experience that any time you see people with guns acting against other people that flashes through your mind. As a Jew, you tend to identify with the underdog.”

When he covered the war in the Balkans, he found himself identifying with the Muslims over the Serbs.

“I was on the side of the Muslims because they were the underdog,” he said.

Norman continues to relive his experiences in Vietnam where he saw many good friends lose their lives.

He said he “lost his faith in a foxhole” and became disillusioned with those in charge who tried to convince the soldiers that their mission was a “holy war” and a just cause.

“My problem with faith is that the authorities — religious and legal authorities of the day — were getting my friends killed,” he said. “Faith is cold comfort in combat,” he added.

Norman said that only recently has he come to recognize that faith contains the one thing needed to rebuild lives.

“Faith contains hope and I don’t think a soldier can ever come home without hope.”

Rosenbloom said the Second World War was one of the most meaningful experiences in his life. He believes it’s the only war of the last 50 years that was worth fighting, where there was a clear enemy and winning was absolutely necessary.

“Had Hitler won the war, civilization as we know it today would not exist,” he said.

Nor did he ever forget the day he entered the concentration camp at Dachau and the horror he was confronted with, which he then recorded in still photographs and video footage.

“I filmed what I experienced,” said Rosenbloom.

“I’m not a brave person….But I knew this war affected my life as a Jew and as a human being,” he added.

The three journalists were deeply moved by their wartime experiences and their lives continue to be affected by what they saw and recorded long after serving.

While reporting from the frontlines, Josh Friedman said he often felt he was testing himself to the absolute limit and experienced a real adrenaline rush. “You feel strangely very alive,” he said.

But he admitted that once he was away from the violence, months later, it would then begin to sink in.

“You’re sitting in the movies and you start crying,” he said. “Things were struggling to get out.”

Norman, who is 56, said that writing his memoir about the Vietnam War, which was published in 1990, and continuing to write about war, is his way of trying to come to terms with what happened to him “under the gun.”

“The work I do is trying to figure out why we fight, and why we’re willing to suffer such extraordinary losses consistently, periodically, regularly…,” he said.

For Rosenbloom, the feats of bravery and dedication to ideals he witnessed during the war have always stayed with him.

“War was my teacher,” he said.

For many, the Second World War will always stand apart as a just and necessary war. And in a museum dedicated to preserving the memory of the Holocaust, it will never be forgotten.

Reader Services