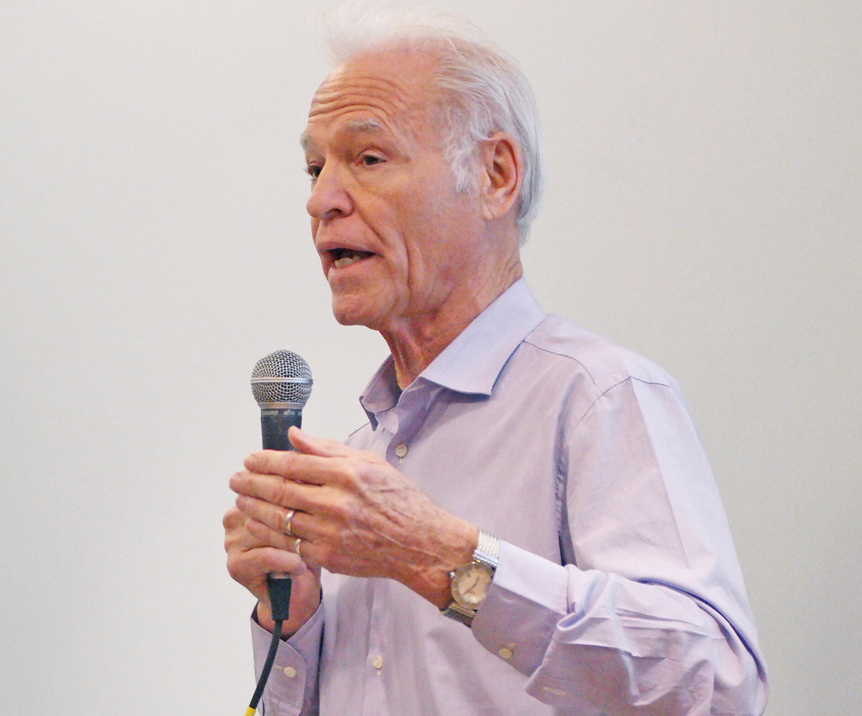

Battery Park City Authority chairman Dennis Mehiel considers allowing only elected officials to speak at authority board meetings while restricting residents to submitting written comments to be a “reasonable approach” to growing calls for more community input.

BY COLIN MIXSON

Faced with growing demands from residents and local lawmakers to allow public comment at its board meetings, the Battery Park City Authority has offered what many are calling a “half measure” — permitting only elected officials to speak at meetings, but restricting residents to submitting written comments — a move that satisfies no one except the governor’s hand-picked appointees on the board, according to state Sen. Daniel Squadron.

“This was never about elected officials’ opportunity to be heard. We have many opportunities to be heard,” said Squadron. “It’s about local residents sharing their local perspective with a board who overwhelmingly resides elsewhere.”

A cadre of Downtown legislators put their names to a letter in April calling on the authority to provide locals the opportunity to speak for themselves at the board’s meetings, with Squadron, Congressman Jerrold Nadler, Borough President Gale Brewer, Assemblymember Deborah Glick and City Councilmember Margaret Chin writing that “public comment is an important part of public engagement.”

Other state authorities, such as the Brooklyn Bridge Park Authority, allow for public comment at their board meetings, but at the BPCA’s June 8 board meeting, authority chairman Dennis Mehiel suggested that allowing elected officials to speak on behalf of locals was a “reasonable approach” to enhancing public participation during meetings, where board members discuss and vote on matters affecting the lives of residents.

“To have the public, through its elected representatives, to be able to come in and talk to us and express concerns, and so on and so forth, I think is a reasonable approach,” said Mehiel.

But Battery Park City residents are deeply unsatisfied with the change of policy, condemning it as an attempt to placate the community while barring them from providing any local meaningful input to a board ultimately accountable only to far-way Albany, according to one community leader.

“The bottom line for me is that the major stakeholders in Battery Park City are its 20,000 residents, who have no voice, and the authority seems unwilling to have a dialogue with us,” said Community Board 1 member Anthony Notaro, who chairs the its Battery Park City Committee. “Even though now the elected officials can talk, nothing’s changed. I have no dialogue with the authority, and they have continually shut out major stakeholders from their decision making process. That needs to be addressed, and this does not address that.”

Some are pointing to the board’s notion of public input as a good reason to shake up the authority’s leadership and install more locals to a group that currently includes only one Battery Park City resident, Martha Gallo.

“This not only reinforced the need for more local stakeholder representation on the board itself, but also could be the spark for interest by the community to consider a substantial change in control,” said Battery Park City resident and CB1 member Tammy Metzler.

But the BPCA insists that its plan is the best means for meaningful stakeholder input, arguing that not only would locals be able to communicate with board members through their elected officials, but the legislators would also be able to engage the board members in discussion, which is often not the case with public comment at other agencies, which allow community members to make brief statements at meetings without replying to them, according to an authority spokesman.

“Unlike the public comment sessions of some other boards, where individuals read statement after statement to members who sit silently and without discussion, our new policy provides for actual engagement between the public’s elected representatives — on any matter those representatives feel appropriate to discuss — and the BPCA Board in an open forum,” said spokesman Nick Sbordone.

But the BPCA has yet to define the nature of this “actual engagement,” or say how much time the board is prepared to devote to it during board meetings. So the result may be even worse than the impotent, ignored, pro forma comment periods at other agencies’ meetings — but these would be open only to elected officials rather than the public.

As for allowing input from residents, that would be allowed under the new policy, but only in the form of written comments — which can be sent up to 24 hours after a meeting and will be included in the minutes. The authority characterized the change as creating the potential for “unlimited” community feedback which would become a matter of public record, to be made accessible online, while also allowing for the authority’s meetings to function smoothly.

“The new policy also enables the public to submit comment on any matter of interest up to 24 hours after the close of a board meeting for review and inclusion in the minutes of that meeting. No time limit, no word limit — and all while creating a record, posted on our website, for the public to draw on for reference and research purposes at any point in the future,” said Sbordone.

Locals are welcome to submit written comments on any subject, however, Mehiel framed the change as giving community members a chance to weigh in on items being decided by board members at the meetings.

But agendas for BPCA board meetings are only made public 24-hours before the meeting, giving locals scant time to compose their comments on those topics, and leaving no guarantee that board members would even see them before casting their votes on agenda items, according to Zeeshan Ott, spokesman for state Sen. Squadron.

The board’s compromise proposal certainly provides for more public input at authority meetings than Battery Park City residents were ever allowed before, but locals still say it falls short of that they were hoping for to improve communication with the notoriously aloof panel that rules over their comminuty.

“They’re extending an olive twig instead of an olive branch,” said Battery Park City resident Tom Goodkind.