BY SAM SPOKONY | Stories about abductions which purposely blur the lines of fact and fiction are certainly nothing new — and in fact it was 16th-century tales of Englishmen falling into the hands of Barbary pirates, and then 17th-century recounting of New England colonists taken by Native Americans, that laid the ground for the wildly popular “captivity narratives” of those days.

Now, “The Kidnapping of Michel Houellebecq” rebrands the captivity narrative with a humorously postmodern stamp, purporting to tell the “real” account of the (actually real) disappearance of the (actually real) French novelist Houellebecq — starring the author as himself.

French novelist Michel Houellebecq gets a home-cooked meal, from the mother of his bumbling captors.

As that true story goes, Houellebecq (whose writing has offended many people, notably including those of the Muslim faith) mysteriously vanished for several days during a promotional book tour through Europe in 2011, leading fans and journalists to speculate on a range of possibilities that included his being taken hostage by Al-Qaeda. The mystery was later compounded by the fact that the author, upon reappearing, refused to explain the circumstances behind whatever took place.

‘Captivity narrative’ tells the (real?) story of author’s disappearance

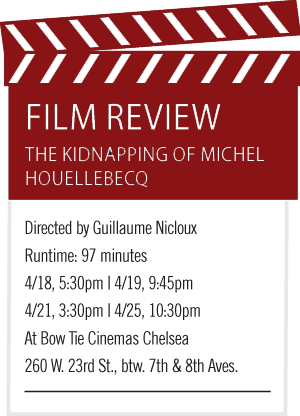

And this new film, directed by fellow countryman Guillaume Nicloux, would have us believe that, yes, Houellebecq was held captive — by a bumblingly comic group of criminal middlemen whose underlying intentions or employers are never quite made clear.

And this new film, directed by fellow countryman Guillaume Nicloux, would have us believe that, yes, Houellebecq was held captive — by a bumblingly comic group of criminal middlemen whose underlying intentions or employers are never quite made clear.

So, after a brief introduction to the wryly philosophical and perpetually cigarette-smoking writer, we find him inexplicably kidnapped by three brothers — the obese head honcho Luc, bodybuilder/martial artist Maxime and emotionally introspective Mathieu. And where, of all places, do they keep their hostage? Why of course, it’s the quaint little country house of the brothers’ charming elderly parents, who later introduce themselves to the placid-yet-confused Houellebecq over a home-cooked meal.

Throughout the increasingly strange ordeal, Houellebecq is kept entertained by his captors with a copious amount of booze and smokes, along with discussions leading to absurd arguments and other forms of incidental bonding that include Maxime teaching the middle-aged novelist how to put Luc in various wrestling choke holds. And the whole array of events — including the hiring of a local prostitute for the protagonist’s enjoyment — definitely hits its comedic goals, drawing laughs with zinger after zinger, even as we continue struggling to understand just what the hell is going on here.

It’s no spoiler to say that Houellebecq eventually makes it out alive — he is, after all, playing himself in a movie about himself — but the question is, what do he and his captors learn about each other, and themselves? How do they go about making the best of a bad situation, and where does it leave them when it’s all said and done?

Keeping to the film’s theme of overall mystery, some of those are of course left unanswered, but some, on the other hand, give engagingly deep insight into the very real mind of one of Europe’s great living authors. And in the end, whether or not one has actually read Houellebecq, we’re left thinking that there’s something remarkably keen about this guy’s uniquely self-deprecating wit, not to mention the feeling that the old captivity narrative — in its most ironically authentic, quasi-fictional form — isn’t dead yet.