By WILL McKINLEY

Volume 21, Number 39 | The Newspaper of Lower Manhattan | February 6 – 12, 2009

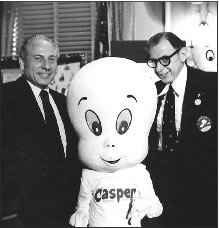

Courtesy Alan Harvey

Harvey founder Alfred Harvey (right) with his brother Leon (left) and son Adam, dressed in costume as Casper at a Boy Scouts event in the 1970s.

From Richie Rich to Wendy the Good Little Witch:

The Art of Harvey Comics

Through April 18

Tues-Sat 12pm-5pm

General Admission: $5,

Children 12 and under: Free

The Museum of Comic and Cartoon Art

594 Broadway, Suite 401

212-254-3511; moccany.org

There’s a g-g-ghost in Soho!

Casper and friends are back at Downtown’s most animated museum

Fifteen years ago, Casper the Friendly Ghost disappeared from newsstands. Harvey Comics, based in New York City for nearly half a century, stopped the presses in 1994 and a wealth of delightfully analog children’s entertainment seemed doomed to recede into history — until Mark Arnold sprang to the rescue.

“I never thought of myself as the savior of the company,” said Arnold, editor of the long-running fan magazine “The Harveyville Fun Times.” “I just thought it was sad that it had dwindled away to nothing. My goal was to give Harvey its due on its home turf for the first time.”

Mission accomplished. “From Richie Rich to Wendy the Good Little Witch: The Art of Harvey Comics” recently opened at the Museum of Comic and Cartoon Art in Soho. The retrospective features original comic book art — much of it in the hands of private collectors like Arnold — from Harvey’s history as a family-owned purveyor of family-friendly entertainment.

“Everybody knows Casper and Richie Rich, even the younger generation, because of the films and the cartoons,” said Ellen Abramowitz, MoCCA chairman and co-curator of the exhibit. “But you say those names to me and I think comic book.”

If you grew up between the Eisenhower and Reagan administrations, you probably agree. Generations of young readers enjoyed the printed exploits of the precocious pint-sized protagonists of the Harvey universe. This was the currency of childhood: acquired with nickels and dimes of allowance money, carried in knapsacks and back pockets and traded on playgrounds and school buses. But because the work was targeted at kids as young as six, the company’s output has often been creatively discounted.

“People who love the Harvey line are almost in the closet about it,” said animation historian and author Jerry Beck. “But these are great children’s stories. It wasn’t just kiddie crap that we threw away. The artwork is particularly handsome and the stories are very clever. It’s really classic American pop art.”

Beck is a creative force behind “Harvey Comics Classics,” an anthology of early appearances of Harvey headliners. Last year’s Richie Rich book sold out its initial print run and “The Harvey Girls,” featuring second-wave feminists Little Audrey, Little Dot and Little Lotta, is due out next month.

“In a sense, the Harvey characters were the complete opposite of what someone would think of if they were trying to create cute comics: a dead kid; a baby devil; a witch; a rich capitalist; a girl who’s obsessed with dots and another who can’t stop eating,” Beck said, laughing. “But there’s something in all of them that we identify with, that we want to be, or already are.”

The otherworldly nature of many of the characters may have its genesis in the company’s earlier, more notorious output. After achieving initial success with superhero titles in the 1940s, founder Alfred Harvey created a stir in the early ‘50s with eye-catchers like “Chamber of Chills” and “Tomb of Terror.” Unfortunately, two of the eyes caught belonged to New York Senator Robert Hendrickson, who convened the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency in 1954 in the wake of psychiatrist Frederic Wertham’s cautionary manifesto “Seduction of the Innocent.”

“People were blaming comic book publishers for juvenile delinquency and the Harvey comics were some of the worst offenders,” Beck added. “So Harvey licensed the characters from Paramount‘s Famous Studios theatrical cartoon line as protection.”

What may have begun as a defensive maneuver grew into a strategy for success. Paramount’s Casper, Baby Huey and Little Audrey became comic book stars, as did George Baker’s hapless private Sad Sack, originally created during Work War II for “Yank, the Army Weekly.” Sad Sack begat Little Dot, who begat Richie Rich and Little Lotta. Casper begat Wendy, Spooky and Nightmare. Hot Stuff begat Stumbo. And in 1957, Alfred Harvey’s future wife Vicki Lorne — whom he met while she was waiting tables at Flatiron landmark Eisenberg’s Sandwich Shop — negotiated the multi-million dollar purchase of the Paramount roster. Casper and his friends landed on TV in 1959 and comics flew off the racks.

“The printed history of this company was great,” said Alan Harvey, eldest son of the founder and editor-in-chief from 1986 until 1990. “They had a circulation of 36 million per year and a pass-along of 6 per issue. They were all over the world, in many languages. It’s amazing how many people were reading them.”

The collaborative nature of comic book production has led to controversy over creatorship of Harvey’s iconic originals. Famous Studios animator Steve Muffatti and veteran Harvey artist Warren Kremer are acknowledged for establishing the colorfully cute “house style” and Alfred Harvey, longtime editor Sid Jacobson, writers Lennie Herman and Stan Kay and artists Sid Couchey, Howard Post, Marty Taras and Ernie Colon all played vital roles in development of the characters. But one fact is free of debate: all of the Harvey heroes and heroines were born and raised in New York City.

“The people who worked on these comics were New Yorkers,” Arnold said. “So there’s an overall toughness and sophistication that comes through in all the Harvey characters. ‘When the going gets tough you keep fighting, because this is New York.’ They don’t say that, but it’s intrinsic in the make-up of the citizens.”

For many post-War, pre-digital kids, Harvey comics were a literary watershed — the first exposure to written humor, witty wordplay and subtle sarcasm, all presented in the clear comic voice of the city in which they were made.

“There were always wise guy gags and puns; that’s New York humor,” said Paul Maringelli, a Harvey production artist in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s. “There were people working there who were born in Puerto Rico and China, but they were all New York guys.”

While the attitude may have been subtly subversive, it never overshadowed the core message of optimism, acceptance and respect. For Alfred Harvey’s youngest son, the subtexual transposition of the Manhattan melting pot to the economically diverse milieu of the comics is a key contribution of the man and the company that bore his name.

“If you think about Richie Rich befriending the poor sandlot kids, that came from my father’s childhood,” Eric Harvey said. “He was a Depression Era child, born in Brooklyn to immigrant parents from Russia. Richie was the ideal unspoiled rich kid who just wanted friends and didn’t care where they came from.”

Unlike much of mid-century America, Harveyville was successfully integrated as early as 1952, when Little Audrey’s friend Tiny was introduced. Tiny’s race was never addressed, nor were the differences between any of the inhabitants of Richville, Bonnie Dell or the Enchanted Forest.

“All the characters co-mingle and respect a diversity of viewpoints, a hodgepodge of what humanity can be, even if it’s little devils or witches or ghosts,” said MoCCA director Karl Erickson. “There’s a sense of community in Harvey Comics, not just in the way they worked but in the ethos they espoused.”

At the opening reception last month in the museum’s spacious loft gallery, Mark Arnold and other fans mingled with artists and members of the Harvey family, including three of the founder’s grandchildren — aged seven months to five years old — mesmerized by Casper cartoons on MoCCA’s plasma screen.

“Alfred Harvey was the genius of comic production,” latter-era artist Angelo DeCesare said, in between posing for pictures. “It was like a Ma and Pa candy store, with the sons coming in and out. They were good people. It was like a family.”

While the best-known characters are now owned by Classic Media (currently planning a Halloween licensing blitz for Casper’s 60th anniversary), the Harvey heirs retain control of Sad Sack and the 1940s-era superheroes and continue to publish under the Lorne-Harvey imprint, in memory of their parents.

“I look at the comics today and I remember when they were drawn,” Adam Harvey said, flanked by his brothers and surrounded by legacy. “Sometimes I get teary-eyed over it, because I miss it. This show is a great tribute to my father and all the artists. I know he’s looking down and smiling.”

For more information on Harvey Comics visit

thft.home.att.net. Jerry Beck blogs about animation at

cartoonbrew.com