BY Ellen Keohane

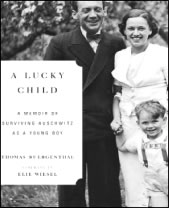

When Thomas Buergenthal first sought an English-language publisher for his book, “A Lucky Child: A Memoir of Surviving Auschwitz as a Young Boy,” he said he was told, “Holocaust books don’t sell.”

“It was the craziest thing—it never occurred to me that the book would be published first anywhere else but in the U.S. and the U.K.,” Buergenthal said over the phone while at his home in Chevy Chase, Maryland.

Ironically, he said, the book first came out in Germany in 2007. There, it became a bestseller. Since then, “A Lucky Child” has been translated into almost a dozen languages. And in 2009, the book finally was published in the U.S.

“It’s a remarkable story,” said David G. Marwell, director of the Museum of Jewish Heritage in Battery Park City. “He’s the last of a generation. It’s important that we listen to him, especially with his experience since the war and how he’s been able to lead his life with that incredible beginning.”

Buergenthal, who recently retired as a judge at the International Court of Justice in The Hague.

Marwell will participate in a discussion with Buergenthal about his life and memoir on Sunday, September 19 at 2:30 p.m. at the museum. Tickets are $5 and free for members.

Buergenthal’s parents owned a hotel in Lubochna, a small town in what is now Slovakia, before their property was confiscated and they had to move into a Jewish ghetto in Poland. Later, his family was forced to work in two labor camps. An only child, Buergenthal first entered Auschwitz with his parents in 1944 at the age of 10. Upon arrival, he immediately became separated from his mother, who he would not see again until December of 1946. He remained with his father at Auschwitz until S.S. Guards removed Buergenthal from their shared barrack. He never saw his father again.

Following the evacuation of Auschwitz, Buergenthal became one of the few children who survived the infamous death march and transport ending at the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in Germany. When he arrived at the camp, Buergenthal’s feet were so frostbitten that he later had to have two toes removed. After the liberation of Sachsenhausen, Buergenthal spent a year in an orphanage in Poland until he reunited with his mother.

Buergenthal said he always wanted to write about his experiences during the war, but didn’t find the time until about five years ago. Many people have asked him about the challenges with writing this book after so many years.

“The truth of the matter is that it’s the easiest book I ever wrote in many ways,” he said. In contrast to the legal books he’s also authored, Buergenthal didn’t need to do any research or cite sources for “A Lucky Child.”

“It just came out,” he said.

Despite waiting so long to tell this story, Buergenthal said he had no trouble remembering most of the events recounted in his book.

“The things I couldn’t remember were dates, for example, and the chronology of events,” he said.

For the most part, Buergenthal equates his survival to luck.

“I think I survived because I was at the right place at the wrong time if you will,” he said. He also benefited from being fluent in both German and Polish.

Luck is a theme throughout Buergenthal’s memoir, which is primarily told in a straightforward tone. For example, in one chapter Buergenthal recounts a story about how his mother once sought out the advice of a fortuneteller.

“And she said that you have a child and the child was ‘ein Glückskind,’ which means a lucky child,” Buergenthal explained.

After the war, Buergenthal’s mother continued to search for her son, although others doubted his survival.

“I’m sure, even though she never quite admitted it, that what the fortuneteller had told her, sustained her belief that I was alive,” Buergenthal added.

When writing the book Buergenthal said he started thinking about how difficult it must have been for his parents. In contrast, he said he believes it was much easier, psychologically, to be a child trying to survive in the camps, compared to an adult. “Probably being a child meant that all I was concerned with was living and getting something to eat—and not thinking about the future or the past,” he said.

After emigrating to the U.S. in 1951, Buergenthal received degrees from Bethany College in West Virginia, New York University School of Law and Harvard Law School. With his language background, he said it made sense to go into international law.

“Gradually, I realized I should really be looking to see if things can be done to prevent others from suffering as I did,” he said.

During his career, he became a judge and president of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. He later served as a member of the Claims Resolution Tribunal for Dormant Accounts in Switzerland, established to look for unclaimed Holocaust-related accounts. He was also chairman of the Committee on Conscience of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Council in Washington D.C.

After a decade serving on the International Court of Justice, Buergenthal recently returned to the U.S. and to academia.

“The George Washington University, where I taught before I went to The Hague, has given me my chair back and my tenure,” he said. “So I’m beginning to teach again.” Buergenthal and his wife’s children live in the U.S., along with their nine grandchildren.

“We just arrived on the first of September. I resigned effective the sixth of September,” Buergenthal said of his position on the court. Now back in the U.S., Buergenthal said he plans to take as much time as he can to promote the book.

“I really feel that very few of us are left who can talk about it in person. We have an obligation to do that,” he said. “The fact that my book couldn’t be published here for a long time because ‘Holocaust books don’t sell’ is a tremendous incentive for me.”