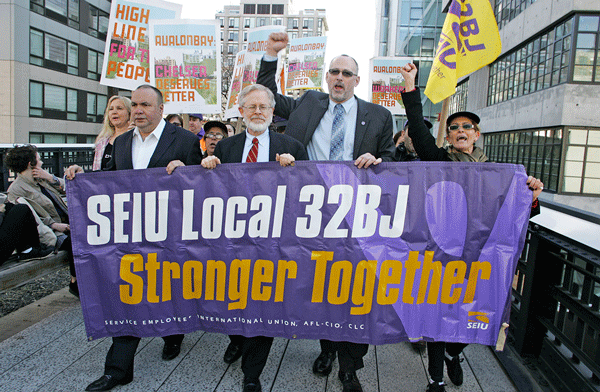

Long road to fair wages: An April 10 rally on the High Line addresses conditions at nearby buildings, where workers earn much less than their unionized counterparts.

BY SAM SPOKONY | ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED 4/11/2014 and UPDATED 4/23/2014 | Hundreds of union workers marched across the High Line alongside non-union workers, elected officials and local advocates on April 10 to call for better wages for the non-union employees of numerous luxury residential buildings in West Chelsea.

Non-union doormen, porters and concierges at ultra-wealthy residences around the High Line make substantially less than their unionized counterparts, and many don’t even get health insurance. The recent march follows months of similar protests around those buildings, where the non-union workers have desperately sought meetings with building management as part of their attempts to organize collective bargaining efforts and improve their working conditions.

“I work 40 hours a week, sometimes more, but I still can’t afford to live on my own,” said Manuel Matos, 25, who makes $12 per hour with no benefits as a concierge at 540 West 28th Street, which is owned and operated by the Ekstein Development company.

“There are million-dollar apartments in that building, so I know can they afford to pay me enough to live on,” said Matos, who lives in Washington Heights.

Juan Olivo, a doorman at 231 10th Avenue, a condominium building, said he recently got a raise from $13 to $17 per hour after six years of work — but he explained that while the building’s condo board had also recently provided him access to health insurance, most of the cost for that insurance began coming out of his own pay, virtually erasing the raise.

“I need a living wage for my family, just so we can try to have a better life and not have to worry about being able to pay for our groceries,” said Olivo, 42, who lives on the Lower East Side and attended the April 10 rally with his 10-year-old son.

Around 90 percent of non-union workers across other parts of the city — including equally affluent areas like the Upper East Side — receive the current union-standard wages of $21 per hour (or around $44,000 per year), according to 32BJ SEIU, the building workers union that led the rally.

“Everywhere else, they pay those workers wages that allow for a middle-class life and a future,” said Rob Hill, vice president of 32BJ, “but not here around the High Line, where they’ve decided that they’re too rich to follow the rules of the rest of the city.”

Among the other non-union-staffed buildings targeted by the protest was 525 West 28th Street — also known as the AVA High Line, a rental building owned by AvalonBay Communities.

tenant association; Assemblymember Dick Gottfried; Rob Hill, vice

president of 32BJ SEIU; and a 32BJ union member marched along the High

Line on April 10 to call for better wages for non-union building

service workers in West Chelsea. | Photo by Sam Spokony.

ELECTEDS EXPRESS SOLIDARITY

Dubbed “Occupy the High Line” by organizers, the protest began at 520 West 23rd Street — also known as the Marias. Developed by the Hudson Companies, the non-unionized 107-unit luxury co-op was also the starting point for an October 31, 2013 Halloween-themed costumed procession that was attended by then-aspiring City Councilmember Corey Johnson (since elected as the District 3 rep) and State Assemblymember Richard Gottfried.

Gottfried attended the April 10 action, which made its way onto the High Line, then back down to street level, at 28th Street and 10th Avenue — at which point the crowd (now at over 200) heard from Gottfried, Hill and State Senator Brad Hoylman.

“We have some very wealthy folks living around here,” said Hoylman, “and they don’t want their workers to be paid a living wage? Shame on them!”

Gottfried pointed out that the West Side building in which he lives is actually a union building, staffed by 32BJ workers.

“And if the people in my building can afford to live with the 32 BJ contract and those standard wages, then certainly the people who live in and develop these [High Line] buildings can easily afford to pay those wages,” he said.

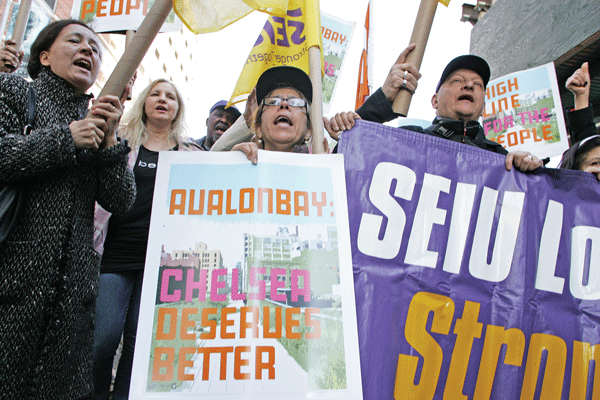

Signs of solidarity: Members of 32BJ SEIU join underpaid non-union workers at an April 10 march.

TRYING TO START A DIALOGUE

Prior to the April 10 march, the elected officials and 32BJ leaders had already put a great deal of effort toward trying to communicate with leadership at two of the High Line area buildings — 231 10th Avenue and 520 West 23rd Street — in hopes of creating a better environment for the non-union workers. But those attempts have yet to lead to any real negotiations.

During the time of the aforementioned costumed rally last October, workers at the West 23rd Street building were in the middle of a two-day strike, in response to alleged intimidation by the building’s co-op board after the workers had begun trying to organize a union in order to boost their wages. And after that failed to lead to any positive results — at least in the eyes of the labor advocates — the workers and their union counterparts staged a sit-in protest inside the building’s lobby last December, specifically seeking a meeting with the 520 West 23rd Street co-op board, according to 32BJ. When that was once again met with silence, another rally followed later that month, but it still didn’t lead to an all-important sit-down meeting.

Finally, during yet another rally inside the building’s lobby in February, Assemblymember Gottfried was able to reach the building’s co-op board via phone, after which the board reportedly promised a meeting to discuss collective bargaining and increased wages. But that meeting never took place, according to Gottfried, 32BJ and the workers — leading them to continue their efforts most recently on April 10.

The 520 West 23rd Street co-op board did not respond to request for comment.

Starting a dialogue with the condo board at 231 10th Avenue on behalf of its non-union workers has been somewhat more successful, according to 32BJ officials, but those talks have also lead nowhere thus far in terms of tangible results for the workers.

Last October, several weeks before the end-of-the-month strike undertaken by their counterparts on West 23rd Street, workers at the 10th Avenue building had held a two-day strike of their own. Following additional protests over the next several months — some of them coinciding with rallies outside the West 23rd Street building — a 32BJ official was eventually able to secure a meeting with Peter Wilson, chair of the 231 10th Avenue condo board, to speak on behalf of the non-union workers, according to 32BJ.

That meeting with Wilson took place in February, and the non-union workers’ demands for better pay and health insurance were discussed — but, as with the other building, nothing came of the talks, and no follow-up meeting took place, according to 32BJ.

Wilson declined to comment on the situation after this newspaper reached him by phone.

So it was with those stifled efforts behind them that the non-union workers marched across the High Line, alongside 32BJ and the elected officials, on April 10, seeking some real steps forward for them and their counterparts at other luxury buildings in the area.

And following the most recent rally, when asked about what the future holds for this push — not only at 520 West 23rd Street and 213 10th Avenue, but also at the other aforementioned buildings — 32BJ President Hector Figueroa stressed that the fight is still not over, regardless of past roadblocks.

“If the luxury buildings along the High Line continue to turn a blind eye to the inequality they are creating in Chelsea, the workers there will have no choice but to take this struggle to the next level,” said Figueroa, in an April 21 email statement sent to Chelsea Now. “They are fighting for their families, and their ability to make a living in this city.”

RESIDENTS CAN AFFORD, SHOULD PAY, UNION WAGES

Looking back to the April 10 rally, Hill, the 32BJ vice president, had specifically called out the wealthy residents of the High Line buildings — and especially the co-op and condo board leaders — for, in his opinion, not caring about the welfare of their less affluent fellow citizens.

“There’s nothing wrong with being rich,” said Hill, “and there are a lot of rich people out there. But most rich people at least know that they got where the got with the help of other people.

“Working-class people built [the High Line], and all these buildings around here are worth what they’re worth because the whole city came together and built the park,” he continued. “And the problem is that the rich people who now live in these buildings have decided that they don’t just need someone to open doors for them, but they also need to spit on those workers as they walk in, because they won’t give them the same benefits and pay that everyone else in this city is willing to pay.”

REBUILDING OR ‘STRAIGHT UP GENTRIFICATION?’

Also, aside from the issue of non-union wages, the April 10 High Line protesters were joined by local residents who called for more affordable housing in West Chelsea, pointing to an overall atmosphere of rapidly rising rents that have forced out both working-class tenants and many small businesses.

“People try to say that this community is rebuilding…but it’s not rebuilding, it’s straight up gentrification,” said Miguel Acevedo, president of the tenant association at Fulton Houses, one of Chelsea’s public housing complexes. “And I’m tired of my residents saying they can’t afford to shop around here anymore, that there are no affordable stores because the mom and pop stores are being forced out.”

Acevedo explained that he hopes to continue teaming up with 32BJ in order to tie the concerns with affordable housing and fair wages together as an issue for both Chelsea and citywide, along with, he hopes, creating more local jobs for his public housing residents.

“We need to take this all over New York, to let everyone know that we were born and raised here, and we’re not going anywhere,” he said. “And if you want to build here, you have to build for the people.”

MEANWHILE, A VICTORY FOR UNION WORKERS

Amid all the struggles on behalf of their non-union counterparts, 32BJ workers celebrated a victory of their own on April 11, when the union announced it had reached an agreement on a new labor contract with the Realty Advisory Board, which represents city property owners in such negotiations.

The agreement, which covers the next four years, will give 32BJ’s 30,000 residential building workers a gradual — but certainly celebrated — wage increase. While the average building worker’s pay will remain at the aforementioned salary of around $44,000 per year until next April, those wages will increase nearly three percent each year, boosting the average salary to around $49,000 by the end of that four-year term, according to the agreement.

“Today we are proud to say that we have made it a little easier for 30,000 New Yorkers to make this great city their home,” said Figueroa, in a 32BJ statement released on April 11. “In a city that has become increasingly unequal, this contract will keep 30,000 building workers on a pathway to the middle class, which will also benefit the communities in which they live.”