At ‘Clybourne,’ it dries into algebra

BY JERRY TALLMER | On the evening of March 11, 1959 (at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre on Broadway) an actor named Sidney Poitier leaped down from the stage to lift a brown, skinny brand-new playwright named Lorraine Hansberry — a Greenwich Village waitress then two months short of her 30th birthday — over the footlights amidst the roar of “Author! Author!” that had exploded as the curtain descended on opening night of her breathtaking “A Raisin in the Sun.”

In a Houston, Texas suburb one year and two months later — May 16, 1960 — a boy named Bruce Norris was born. He would grow up to be an actor-turned-playwright whose Pulitzer- and Tony-winning “Clybourne Park” is umbilically and purposefully connected to Lorraine Hansberry’s half-century-earlier “Raisin in the Sun.”

“I was fixated on that play,” Norris has said, “because it had that great slapping scene where Lena [the powerhouse Mama Younger] slaps Beneatha [the rebellious Hansberry-like 20-year-old daughter] and makes her say: ‘In my mother’s house there is still God.’ ”

The link between the two plays is a meachy little white man named Karl Lindner — a white man who comes to try to bribe a black family not to move into the house they’ve just bought in the white Chicago suburb of Clybourne Park — only to be reborn as a sort of doppelganger called just plain Karl in the first half of the Norris play. This Karl is a grouchy, bitterly disgruntled white homeowner in Clybourne Park who is selling his house to a black family (the unnamed “Raisin” family) come hell or high water — not for idealistic reasons, but quite the opposite.

The plot gets even more complicated (though clear enough on stage) when the actor (the excellent — but they’re all excellent — Jeremy Shamos), whom we’ve just seen as Karl, now appears as a hard-bitten cynic named Steve who smokes out the racism (including black anti-white racism) of a long since gentrified interracial Clybourne Park. The issue now is the height of the rooflines in that tight-knit community. But underneath that crisis is — you guessed it — what somebody might speak of as “enlightened racism.”

Pam MacKinnon, the 44-year-old director of “Clybourne Park,” may know Bruce Norris as well as anyone on earth.

“He went to an ostensibly desegregated but de facto segregated Houston high school,” says MacKinnon. “He thought the film of ‘Raisin’ was fantastic, and then learned it had been made from a play.

“As a white boy and man-to-be and aspiring actor, he realized the only role in ‘Raisin’ he’d ever get to play was Karl Lindner. And he saw his parents and his parents’ friends in Karl Lindner. So he hooked into [Lindner] in two different ways.”

“I identified with Karl and I identified with all of my culture” — white suburban culture — Norris has revealed. What took the scales off the future playwright’s eyes was reaching maturity in a big city called Chicago.

This playgoer hates to say it, but Lorraine Hansberry’s Karl Lindner (vividly remembered from that Barrymore Theatre over all these years and preserved forever on film by John Fiedler) is a great deal more discreet and therefore more insidious — more dangerous — than Bruce Norris’s purely angry armchair-anchored Karl.

But then discreet is hardly the word for this hard-bitten drama that has men and women, some white, some black, throwing the ugliest words in the language at one another by way of racism in disguise, only to bring down the house — not a dwelling place but the howling ha-ha-ing audience — with the ugliest word of all, spoken in the play by a pissed-off young black woman.

Frank Rich, drama critic gone politico-socio essayist, did an endless piece in New York Magazine heralding “Clybourne Park” for telling us fellow Americans in theatrical code what one thought was already plain as day — or dark as night. Night in a gated community, for instance, at somewhere called Sanford, Florida, or almost anywhere in the great state of Arizona, or along hundreds of the frisky sidewalks of good old New York, or anywhere and everywhere the ultimate object of all that hatred is a Negro president of the United States that Mama Younger — and Lorraine Hansberry — never lived to see.

My question — one of my questions: Does laughing at this so-called comedy’s exposures of racist and economic and social hypocrisies remove the poison of racism from one’s own innards? Which is a point within a point, if you see what I mean.

I made a big mistake in the run-up to this dispatch. An unfair mistake. I reread “A Raisin in the Sun.” Virtually every line set emotions afire in a way a hundred “Clybourne Parks” could never do (or, to be fair, would never want to do).

Try this for size:

MAMA YOUNGER: No…something has changed. You something new, boy. In my time we was worried about not being lynched and getting to the North if we could and how to stay alive and still have a pinch of dignity too.

Or this:

KARL LINDNER: You see in the face of all the things I have said, we are prepared to make your family a very generous offer…

BENEATHA: Thirty pieces and not a coin less!\

Or this:

BENEATHA (vis-à-vis her wrecked brother, Walter Lee Younger): Love him? There is nothing left to love.

MAMA: There is always something left to love. And if you ain’t learned that, you ain’t learned nothing.

Pam MacKinnon of Evanston, Illinois and Buffalo, New York has been good friends with Bruce Norris (of Houston and Chicago) ever since they each moved to New York City 16 or 17 years ago and their careers began to take off.

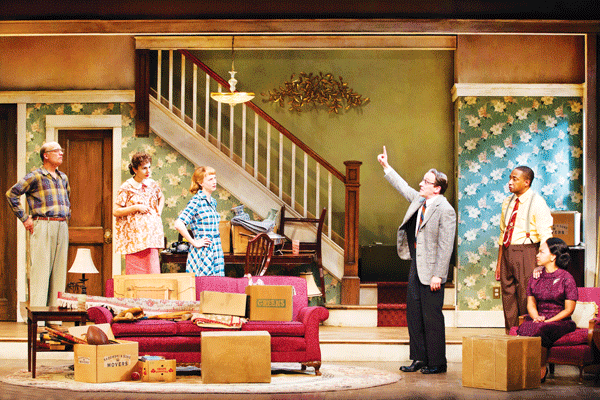

“Clybourne Park” may be built like an algebraic equation — the same seven actors of Act I gerrymandered into precisely seven other roles 50 Pirandellesque years later — but if you listen hard you may also catch some phrases in Act II borrowed from the above-mentioned president’s 2008 election campaign.

“All I knew about ‘Clybourne Park’ until about three years ago,” the director says, “was that it was loosely, loosely, loosely based on ‘Raisin in the Sun.’ ”

So, Ms. MacKinnon, does “Clybourne Park” leave you feeling more pessimistic or optimistic?

“Oh, it depends. Each time I watch it I bring something of myself to it. Some days I come away with lots of hope. Other days I certainly do not have that feeling. I think it’s interesting that at the end of the play, Bruce brings together its most optimistic and most pessimistic characters.”

Fifty-three years ago I walked out of the Barrymore Theatre at the end of the performance as if in a trance. The girl who was with me said four words: “I’m all shook up.” I think it will be a good long time before “Clybourne Park” shakes me up like that.

CLYBOURNE PARK

Written by Bruce Norris

Directed by Pam MacKinnon

Through Sept. 2

At the Walter Kerr Theatre

219 W. 48th St. (btw. Broadway & Eighth Ave.)

For tickets ($30-$127), call 212-239-6200

or visit telecharge.com