BY YANNIC RACK | In the Village, there’s usually more to a building than meets the eye.

The plaster facade of One if by Land, Two if by Sea at 17 Barrow St, which was taken down by the restaurant’s owners two weeks ago amid much community outrage, turned out this week to have a longer and richer history than many thought.

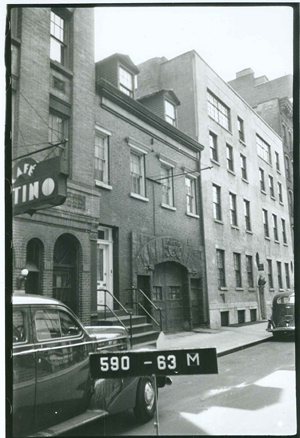

Andrew Berman, the director of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, dug up a tax photo of the building from 1940 that shows the two-and-a-half-story brick structure with its signature archway already in place.

This contradicted a statement from the restaurant owners, who sought to justify their actions by claiming to restore the building by exposing its original 1834 steel beams underneath the facade, and said they believed the plaster archway to date only from the late 1960s.

It is still unclear what the Landmarks Preservation Commission will decide in respect to the archway. It could request that the facade be reconstructed as it was before, which is also what the building’s owners would prefer.

“We are meeting with the owners [of the restaurant] after the 17th and they have assured us that they will comply with Landmarks’ decision,” said Colleen Goujane, who still lives above the restaurant with her husband, Oscar. The couple sold the restaurant to its current owners in February.

“As the owners of the building we are very happy to see that there is affirmative proof that the facade dates from an earlier time,” she said. “We are confident that Landmarks will allow us to build it back as it was in the photograph from 1940.”

But it turns out the archway might be even considerably older than that.

Ellen Conway Bellone, whose grandfather William Aloysius Conway bought 17 Barrow in the early 20th century, told The Villager that the facade was added in 1897 — more than 40 years earlier — when the building was turned into a blacksmith shop.

She said her grandfather worked for a man named Michael Hallanan at the time, who was the inventor of an elastic horseshoe made of vulcanized rubber that made him wealthy.

“The object of my invention is to provide a rubber horse shoe forming a complete closure of the hoof, and having an improved means of securing it to the hoof, and which shoe will form a combined shoe and pad, including a frog, the whole affording a firm bearing for the horse, and yielding to avoid all jar,” reads the patent description, published in 1893.

Hallanan employed Conway and later sold the shop to him (the men were both immigrants from Ireland), but the archway had already been added by then, to make the building accessible to horses.

“It was done because they needed an opening to get the horses in the shop, and that’s a given. Before that it was a different kind of opening,” Bellone said over the phone from New Orleans, adding that the archway was only painted white after it was sold by her uncle in the 1960s and became One if by Land.

Bellone still owns a newspaper clipping from 1928, when the New York Times Magazine interviewed Conway about his plans for the future, now that automobiles were slowly replacing horses and the need for horseshoes.

She also likes to tell the story of when her grandfather made a giant horseshoe for Charles Lindbergh to accompany the aviator on his famous 1927 flight from New York to Paris.

Her grandfather eventually converted his operation into an artisan workshop, where anyone could pay to use the forge. Later, when Bellone’s uncle and his wife started spending more time in Florida, they rented out the ground floor as a spaghetti restaurant called simply “17.”

Conway died in 1944 but the family kept living in the building until it was sold by Bellone’s uncle; she once spent a summer there herself and remembers the building well, even though she left New York City in 1960.

“I think it should be restored to the archway because it was made an archway so that horses could go through,” the 79-year-old said. “For most of its life it was a blacksmith shop, you know. I think it’s called Greenwich Village because it was a village. It’s quite a leap of the imagination to think of it as a village now, and I think to keep the artifacts that remind you that once it was a village, is important. And a blacksmith shop certainly reminds you of that.”