By Albert Amateau

Thirty years ago this spring, state and city engineers and planners proposed a six-lane highway, to be built mostly underground on 220 acres of new landfill in the Hudson River with 98 acres of parkland and about 100 acres of development on top.

The plan, issued in April 1974 and dubbed “Westway” later that year, was designated part of the federal highway system and had broad support. It was to replace the crumbling elevated Miller Highway built in 1927 over the West St. and 12th Ave. waterfront between the Battery and 72nd St.

A section of the elevated road near Canal St. had collapsed in December 1973, but environmental advocates saw the $2 billion-plus landfill highway plan as a disaster and they eventually went to federal court to stop the project.

Federal Judge Thomas P. Griesa ruled in August 1985 that state and federal agencies had given tainted testimony about the impact on Hudson River striped bass by the proposed landfill between Battery Park City and 30th St. and the project was officially dropped in September.

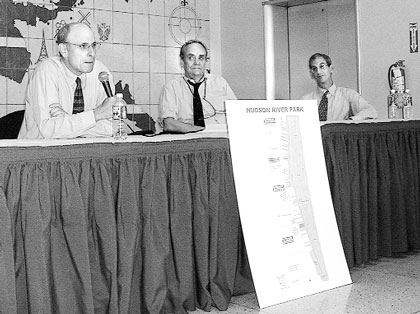

Some of the old warriors who fought the battle of Westway gathered on Pier 40 at the end of W. Houston St. last week for “Westway Revisited,” a postmortem on the not-quite-forgotten project. On July 20, Friends of Hudson River Park, will convene another forum on the replacement project — the recently completed Route 9A and the Hudson River Park — the latter now taking shape on the riverfront.

“It will be ‘The Story of Hudson River Park, Part II,’ ” said Albert Butzel, president of the Friends, regarding the 6 p.m. July 20 event also to be held on Pier 40.

Butzel, currently engaged in advocacy for public space projects including Hudson River Park, Brooklyn Bridge Park and Governors Island, was the lawyer — representing New York Clean Air Campaign, the Sierra Club and the Hudson River Fishermen’s Association — who went to court to stop Westway. Associated with Butzel was Mitchell Bernard, currently with the National Resources Defense Council, who argued the striped bass issue in federal court that put an end to Westway.

“There was an enormous amount of political and economic power in favor of Westway in 1982,” Bernard recalled in an interview this week. “Mayor Koch was for it, Governor Cuomo and President Reagan were for it. So were the unions, the banks and the real estate industry. But the decision proved that if you have an independent and courageous judge, you have a chance,” Bernard said.

Bernard recalled that at one point, a federal highway official gave testimony on a Friday about the effect the landfill would have on aquatic life in the river, and then came back on Monday and changed his testimony. “It was a fraud of major proportions,” said Bernard regarding a 1984 environmental impact statement on Westway by the Army Corps of Engineers and highway agencies.

A leading opponent of Westway, Marcy Benstock, then and now director of New York Clean Air Campaign, also attended last week’s forum. Benstock remains a severe critic of the Hudson River Park Trust, the state and city agency now building the park. “She asked me whether I thought current use of the piers for non-water-related uses was legal,” Bernard recalled, “but I couldn’t answer because I don’t know — I’m not involved in the park now.”

Craig Whitaker, an architect and planner who also teaches at New York University’s Wagner School of Public Administration, was the author of the 1974 Westway proposal when he worked for the city. He still believes Westway was a missed opportunity to create a vast amount of parkland at federal expense. Whitaker was on the panel last week and in an interview later recalled his role in the project, which began in the early 1970s.

“We did core samples of the Miller Highway and found the middle layer was powder. That meant that some contractor in the 1920s shorted the city on specifications,” he said.

“We didn’t think New York would stand for an at-grade highway,” said Whitaker, recalling that inclusion in the federal interstate system meant that 90 percent of the project would come from the federal funds. The first idea was for a road to be built over the river on piles with a roof for parkland. “But we discovered that the feds would pay only for the piling and the roof, so we put it in the water and got the feds to agree to pay for the highway and 2.5 miles of continuous parkland,” Whitaker said.

One estimate of Westway’s cost was $2.3 billion, but $1.9 billion was for the park, Whitaker said. “It was all or nothing,” said Whitaker about the fight over Westway. “We couldn’t get anyone on the other side to talk to us.” The landfill was to be zoned about half for development and half for park. “We could have built affordable housing, or made it all park, but there was no one to negotiate with,” he said.

Air quality was an early cause for denial of a permit. But in May 1980, after three years of hearings, the state Department of Environmental Conservation granted the permit over the objections of environmental groups and reservations by the federal Environmental Protection Agency.

“Carbon monoxide is the main pollutant, but it disperses very quickly in the open air and we had three vents,” Whitaker recalled. The project also included filters to trap particles from the tunnel exhaust.

Whitaker believes that Westway would have not increased auto traffic. “It was a six-lane highway and the new Route 9A is a six-lane highway that handles 135,000 vehicles a day,” he said.

But it was fish that ate Westway. In May 1984, the Corps of Engineers issued a draft environmental impact statement that said Westway landfill would have a “significant adverse impact” on striped bass.

“As soon as I read the word ‘significant’ I knew we were finished,” Whitaker said. He believes the Corps of Engineers used the word “significant” without realizing it had legal meaning and could sink the project. In June 1984 more than 250 witnesses testified pro and con about Westway, and in November the final environmental impact statement dropped the word “significant.”

In March 1985, the environmental groups went back to federal court, and in August, Judge Griesa issued his historic ruling that the Corps of Engineers and the Federal Highway Administration failed to comply with the Clean Water Act and the National Environmental Policy Act.

Meanwhile, a Sept. 30, 1985, deadline was looming by which time the state had to decide whether to trade in the federal highway funds for aid to mass transit and local roads or lose that option. In September, the U.S. Court of Appeals upheld Griesa, and on Sept. 19, Cuomo and Koch exercised the trade-in option.

Noreen Doyle, vice president of the Hudson River Park Trust, was also at the June 8 forum. “I wasn’t around for the Westway battle and I found the event fascinating,” she said later.

“But if Westway had proceeded, the park would have had a very different look. There wouldn’t have been 400 acres of water designated as a marine sanctuary and I doubt that we would have been building the first of four non-motorized boathouses in the park,” Doyle said.

Read more: https://www.amny.com/opinion/