Work from home is the biggest driver keeping mass transit ridership stuck below pre-pandemic levels, MTA Chairperson Janno Lieber said Wednesday.

Safety concerns are also to blame, said Lieber, but transit data show that New Yorkers from blue-collar areas have returned to the subways and buses in greater numbers, even though they live in neighborhoods with higher crime rates.

Residents in wealthier parts of town with lower crime rates — who are more likely to have a job with a remote option — have been slower to travel back to the office for work, according to the transit chief.

“We know that safety is on people’s minds, we know that COVID is on people’s minds. The demographics or the geography of our ridership loss suggests it’s more from the work from home issue,” Lieber said on the Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC on Aug. 17.

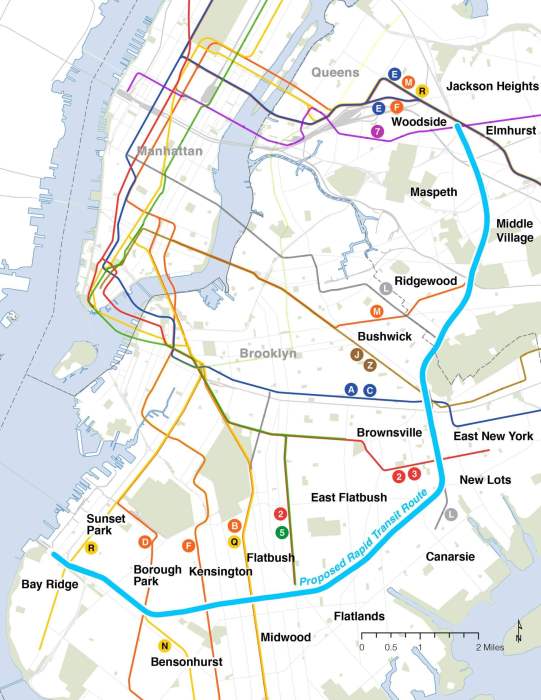

Boroughs outside Manhattan are showing higher rates of daily trips, which is where many of the city’s workers live who don’t have a choice but to show up to their jobs in-person.

“People who are in neighborhoods that maybe have more crime, but they’re essential workers, in the boroughs — in particular in the Bronx and Brooklyn and Queens — they’re arriving at a higher percentage relative to pre-COVID than the folks who live in the neighborhoods that have less crime,” said Lieber. “In those more affluent neighborhoods there are more white-collar workers who are working from home.”

“All of those issues are playing a role in the loss of ridership that we are undergoing,” he added.

Ridership returns have been uneven throughout the pandemic.

Outer-borough trips and journeys by essential workers rebounded quicker in 2020, a 2021 report by then-City Comptroller Scott Stringer found.

Daily trip numbers rose as high as 90% of 2019 figures in some working class areas of the Big Apple, according to an MTA report from May, while citywide rates have remained flat at just below 60% for months.

Weekend ridership rates have done better at nearly 80% in June, and one transit advocate said the state must boost service outside of the traditional rush hours, without making cuts to existing schedules.

“Right now weekend service is a bright spot for ridership, but it’s miserable for riders,” said Danny Pearlstein of the group Riders Alliance. “Riders are suffering through very elaborate construction detours and waiting regularly 20 or 30 minutes for a train on the weekend.”

“People from the neighborhoods [Lieber] is talking about, many of whom do not work in offices, also don’t work nine-to-five,” said Pearlstein.

Office occupancy in the city cracked 40% for the first time during the COVID era in June, the City reported.

As the pandemic drained the MTA of its passengers, city and state officials have frequently focused on crime and unhoused people seeking shelter in the subway system.

At the beginning of the year when the Omicron variant tore through the city, Lieber also blamed a ridership setback on fears of homelessness people in the subway and crime.

Mayor Eric Adams deployed a record number of cops into the system to create an “omnipresence” of law enforcement underground.

Subway riders still listed safety as their top concern in a survey released by the MTA last month.

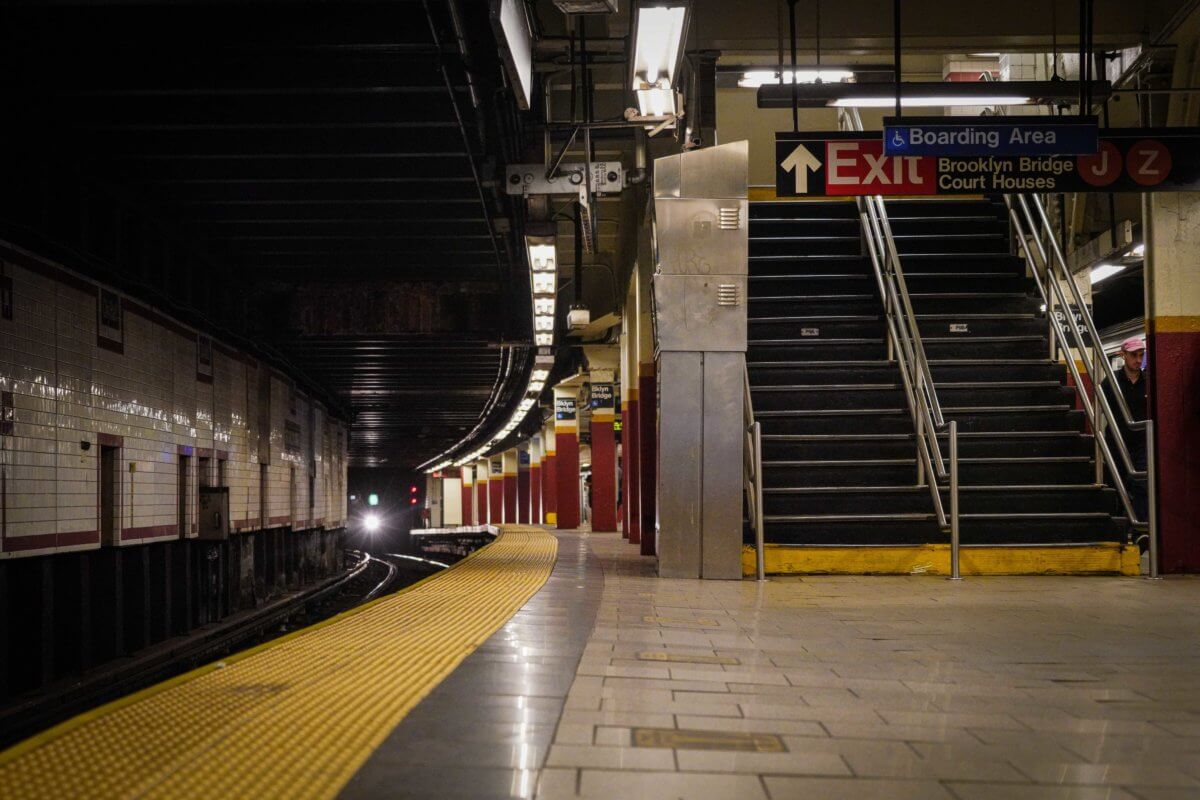

While transit made up less than 2% of citywide crimes so far this year, according to NYPD statistics, a series of high-profile attacks on the subways shook the city as it was trying to come back from the pandemic.

In January, a man shoved rider Michelle Go in front of a subway train in Times Square; in April, a shooter opening fire on a crowded train in Sunset Park, Brooklyn; and in May another gunman killed Goldman Sachs employee Daniel Enriquez on a train heading over the Manhattan Bridge.