You can’t properly discuss the history of Major League Baseball without the New York Yankees.

The most successful team in North American sports history has become synonymous with winning throughout its 117-year history.

The interlocked “NY” has become an icon, their pinstripes fashionable, the facade archetypal, and a plot of land — well, now two plots of land — in the Bronx revered as holy grounds.

The Yankees’ brand obviously did not just become a baseball institution overnight, but one key event that helped the organization become the team that defined baseball happened on Friday’s date, 107 years ago.

It’s when the Yankees became the Yankees.

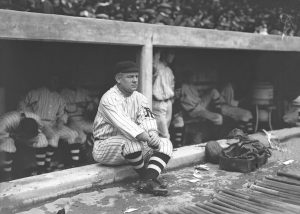

On April 10, 1913, the American League’s New York baseball club dropped a 2-1 decision at Griffith Park in the nation’s capital to the Washington Senators.

The New York side beginning its 11th year of play was shut down by Hall-of-Fame pitcher Walter Johnson, one of the premier hurlers of the time, who was lights out after allowing a run in the opening inning.

An inauspicious start for the New Yorkers, who debuted the name “Yankees” on that very day following 10 seasons being known as the Highlanders.

It was a much-needed rebrand based on play alone. The franchise was coming off a 50-102 1912 campaign which saw them finish at the very bottom of the eight-team American League.

Actually, winning wasn’t a familiar concept at all considering they had just four winning seasons in their first 10.

But why the change? It’s an incredibly convoluted story over 13 years that included treachery, under-the-table deals, and one of the greatest managers in Major League Baseball history who never donned a Yankees cap.

****

At the turn of the 20th century, the National League was nothing short of a monopoly that owned the baseball landscape despite a bevy of professional leagues.

Looking to challenge the NL’s standing, the president of the Western League, Ban Johnson, purchased three Eastern teams and formed the American League in 1900, which gained prominence as a major league just one year later.

His original desire was to put one of those teams in New York, but the move was blocked by the Giants — who played their games at the Polo Grounds in upper Manhattan and had enough political power to keep the AL out of the Big Apple.

Instead, Johnson formed a team in Baltimore and named them the Orioles (sound familiar?), where they would play for two unremarkable seasons.

****

These Baltimore Orioles are not the franchise that currently plays in the American League East alongside the Yankees. In fact, the franchise known today as the Orioles was founded in 1901 as the Milwaukee Brewers (again, sound familiar?), though they lasted just one season before moving to St. Louis and becoming the Browns.

The Browns would play in St. Louis until 1953 before moving to Baltimore and becoming the Orioles for the 1954 season.

The Baltimore franchise established for Johnson’s American League beginning in 1901 was a reincarnation of an original Orioles team that dominated the National League from 1892-1899 after making the jump from the American Association.

They won three straight pennants from 1894-1896, winning 68% of their games during that stretch (266-125) while boasting Hall of Famers such as first baseman Dan Brouthers, shortstop Hughie Jennings, outfielders Wee Willie Keeler and Joe Kelley. Their catcher, Wilbert Robinson, would also become a Hall-of-Fame manager with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

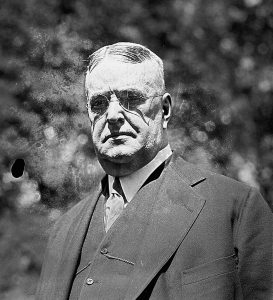

But it was their short-tempered third baseman, John McGraw, who is the most recognizable member of the team — and the man that plays an enormous role in the formation of the Yankees.

When rumors began to swirl before the 1900 season that the National League would drop the Orioles and two other teams, McGraw attempted to team up with Johnson to help form the Baltimore American League club. But the inability of the AL’s Orioles to secure a full-time ballpark forced McGraw to return to his NL club, where he had been player-manager for the 1899 season.

Just weeks later, the National League announced that the Orioles would be dropped. The remaining NL clubs were given rights to the players of the now-defunct teams where McGraw was picked up by the Brooklyn franchise.

McGraw refused to report and as punishment, was sold to the lowly St. Louis Cardinals for the 1900 season.

To little surprise, McGraw had no interest in playing for the Cardinals, who hadn’t finished higher than fifth since joining the National League in 1892. He decided to hold out through late May until the Cardinals granted him free agency — a concept unheard of during the time of the reserve clause.

During this time, Johnson was working on making the American League a major league, asking the National League to establish teams in big cities that already had pro clubs.

When NL president Nick Young turned down the deal, Johnson went rogue.

Johnson established teams in NL-inhabited cities like Boston and Philadelphia while adding franchises to former NL homes including Baltimore — a consolation city after the Giants blocked Johnson from putting a team in New York.

Despite their differences — Johnson was a pious man while McGraw was known for cheating and violent tendencies toward umpires — the latter was allowed to take over the American League’s Orioles with the assurance that a move to New York was on its way.

McGraw was even given the responsibilities of visiting with shareholders in New York while looking for potential places to build a ballpark.

But McGraw never got so far.

Missing a month due to injuries sustained in a May game when he was spiked by Detroit’s Dick Harley, McGraw recognized that Johnson had no plans for him to make the jump to New York.

During his recovery period, he met with noted gambler and racehorse owner Frank Farrell (remember that name), who wanted in on an AL franchise in New York followed by a sit-down with Giants owner Andrew Freedman about future managing opportunities.

Freedman also had reason to despite Johnson and the American League. He originally hoped to sell his NL team to Cincinnati Reds owner John Brush and buy stock in the future AL New York team, but Johnson originally denied it.

McGraw’s last straw came on June 29 when he was indefinitely suspended by Johnson for berating an umpire and decided to jump ship.

Just nine days later, on July 8, 1902, McGraw’s four-year managing deal with the Giants was revealed while he helped Brush and Freedman buy 201 shares of the Orioles.

It allowed the trio to plunder the Orioles and steal most of their players while McGraw began a 31-year tenure as Giants manager. Shortly after, Freedman sold the Giants to Brush and proceeded to bolt from baseball.

****

Ahead of the 1903 season, despite Brush’s attempt to continue the Giants’ blockade of the city, both the American League and National League agreed to an AL franchise moving to New York.

The man that helped get it done? Farrell.

He and new co-owner Bill Devery — a former New York City chief of police — bought the gutted Baltimore franchise for $18,000, named Joseph Gordon president, and moved the team to a hastily-built Hilltop Park in the Washington Heights section of Manhattan that could not be touched by Brush.

***

The New York club was nicknamed the Highlanders thanks to Hilltop Park’s location near the highest point of the city between 165th and 168th streets and as a nod to their president, Gordon, whose surname coincided with the famed British military unit, The Gordon Highlanders.

As customary for every American League ballclub, though, the Highlanders were also referred to in passing as the New York Americans to help distinguish them from the National League club headed by McGraw.

While they did not attain much success under the nickname as mentioned earlier, McGraw still saw them as a threat — and never needed an excuse to stick it to Johnson’s American League.

The Giants were running away with the National League pennant in 1904 as baseball prepared for its second-ever World Series between the NL and AL victors. But McGraw boycotted the Fall Classic to ensure the AL’s second-place Highlanders did not have an opportunity to not only compete in the Series.

The last thing McGraw wanted was Johnson’s team that shared his city to win the title, inaugurally won by the AL’s Boston Americans (Red Sox) in 1903.

It was during that 1904 season, however, that the “Yankees” name was first connected with the Highlanders. It is widely believed that the name was originally penned by New York Press editor Jim Price, but author Barry Popik insisted to amNewYork Metro that “Yankees” first appeared in an April 7, 1904 edition of the New York Evening Journal.

The name and a shortened version, “Yanks,” was easier to fit in headlines while providing a nod to the “Americans” moniker. Yankees was a term that gained its prominence as a label for the Union during the Civil War.

Despite McGraw and the Giants’ animosity toward the American League, relations warmed in 1911 after the team’s home, the Polo Grounds, burned down.

The Highlanders allowed the Giants to play their home games at Hilltop Park while the larger, more impressive stadium was rebuilt.

Two years later with the stadium set to reopen in 1913, the Highlanders were allowed to move to the brand-new venue, which was based along the Harlem River — which is anything but elevated land.

A new home prompted the franchise to move away from its Highlanders nickname and with the media already using the Yankees moniker, an official rebrand was made. They would play at the Polo Grounds for 10 seasons until the original Yankee Stadium in the Bronx was completed.

But it was on that day, April 10, 1913, that the New York Yankees took the field and their first enormous steps toward conquering a city and America’s Pasttime.

And it was anything but easy just to get to that point.