While a picture is worth a thousand words, words can also affect the meaning and impact of pictures. And an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art explores the photographs of Dorothea Lange, and how accompanying texts, from both Lange and others, have shaped the meanings of her work.

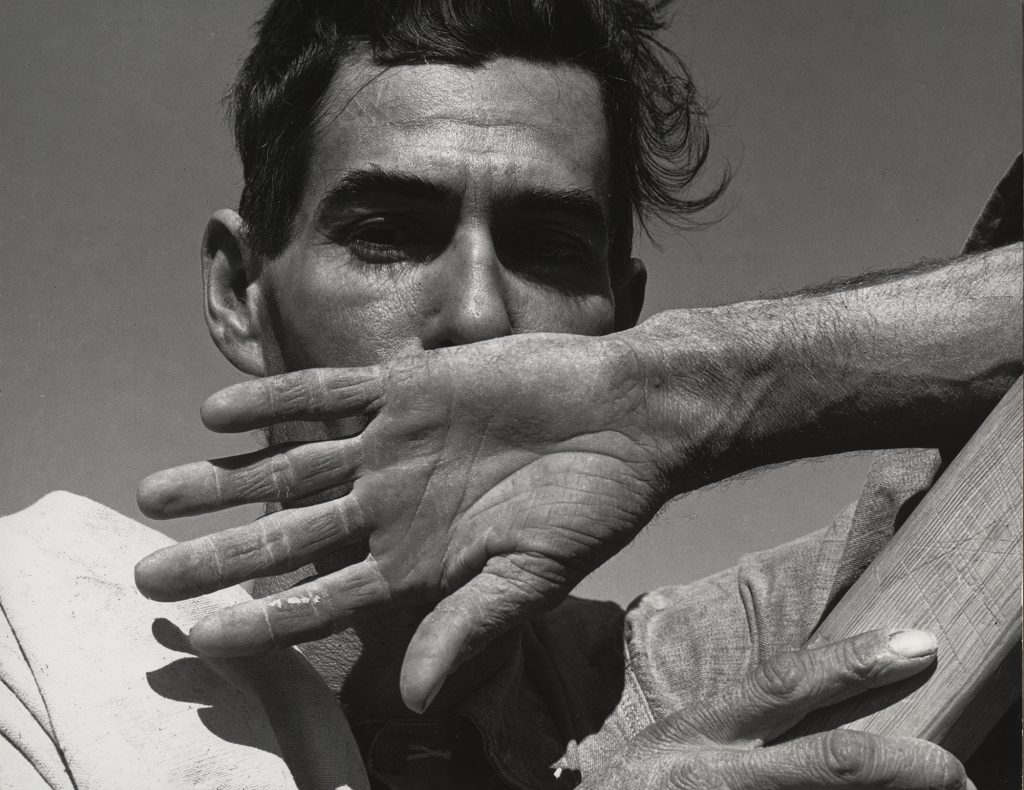

“Dorothea Lange: Words and Pictures,” spans the career of Lange (1895-1965) in sections, examining her work as a chronicler of American life and events and suffering in the 20th century.

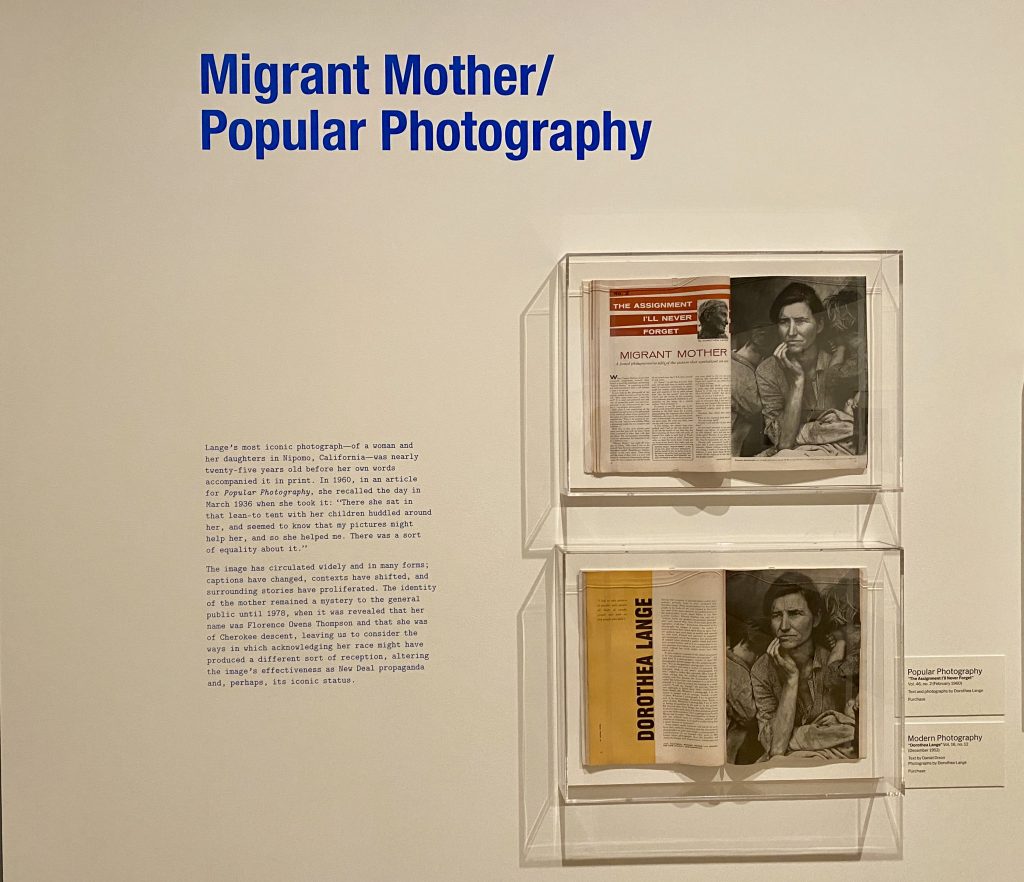

Lange’s most famous photo, the iconic Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California, 1936, was taken during the years when Lange worked for government agencies to raise awareness about the catastrophes surrounding the Great Depression and Dust Bowl era. It was printed in many publications with various captions and having different titles, the exhibition notes, though it wasn’t until 1960 that Lange’s words joined with the photo.

Lange described the photo in an article in Popular Photography: “There she sat in that lean-to tent with her children huddled around her, and seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it.”

The exhibition mostly goes in chronological order through Lange’s career, starting early on in 1933 with Lange photographing effects of the Great Depression in San Francisco.

An article in Camera Craft magazine by an early supporter described the social importance of Lange’s photos. Another article around that time, by agricultural economist and Lange’s future husband Paul Taylor, would use Lange’s photos to accompany an article of his on labor conditions. Both articles in their own way helped increase awareness and circulation of Lange’s work, the exhibition notes.

Other sections include exploring Lange’s work in two books, the 1938 “Land of the Free,” described as “a book of photographs illustrated by a poem” by poet and the book’s author Archibald MacLeish. And there was the 1939 book by Lange and Taylor, “An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion,” which included quotes from displaced people and migrant workers photographed by Lange, along with field notes, newspaper excerpts and folk song lyrics.

“It seems both timely and urgent that we renew our attention to Lange’s extraordinary achievements,” said curator Sarah Meister in a statement. “Her concern for less fortunate and often overlooked individuals, and her success in using photography (and words) to address these inequities, encourages each of us to reflect on our own civic responsibilities.”

Lange’s photos were also included in a 1941 book, “12 Million Black Voices: A Folk History of the Negro in the United States,” with text by the writer Richard Wright and photos from the Farm Security Administration to depict images of black life in America. The impact of text could also be seen in Lange’s time with that government agency, when “shooting scripts” were given to photographers for capturing people’s lives. One script asked for “Signs—any sign that suggests rubber (or other commodity) shortage, rationing, etc.”

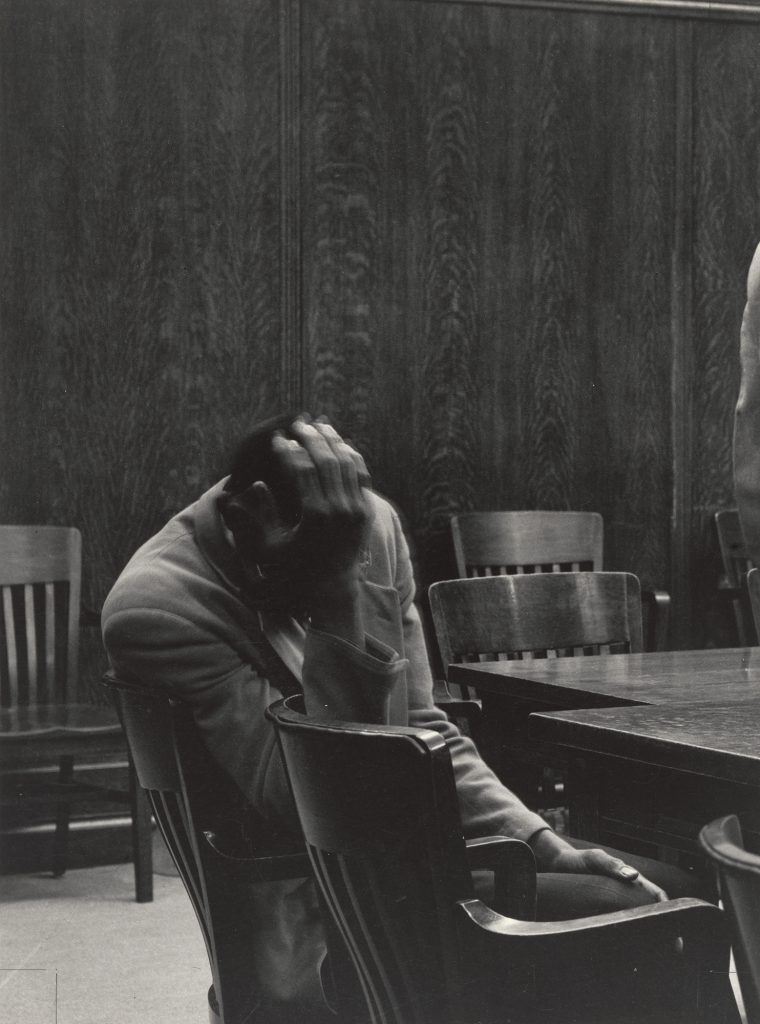

The exhibition also includes Lange’s work depicting life during World War II, including images of Japanese Americans sent to internment camps, with those images initially held from being released. And Lange’s photo essay of a public defender in California and the position’s role in the judicial system.

There are also quotes from Lange highlighted throughout the exhibition, including one from 1960-61 which reads, “All photographs—not only those that are so-called ‘documentary,’ and every photograph really is documentary and belongs in some place, has a place in history—can be fortified by words.”

The exhibition will run until May 9, and more info is at www.moma.org.