In the canon of human self-invention, nothing rivals the power of dress. Not religion. Not rhetoric. Not conquest. The garment has always been a second skin—a chosen skin—stitched with the sacred right to be seen.

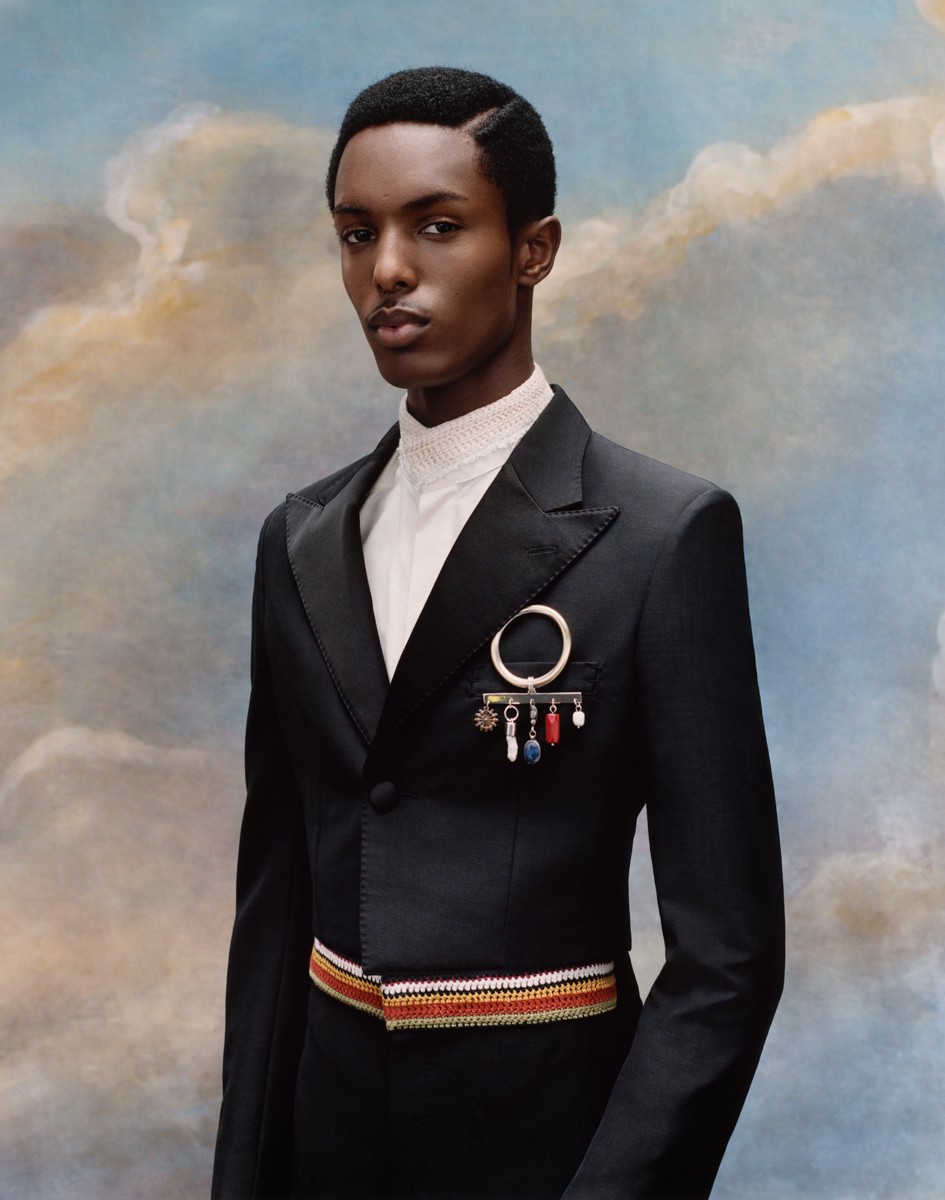

At “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style,” on view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through Oct. 26, that skin is embroidered with defiance, subversion, ingenuity, and grace. Here, dress is not decoration. It is authorship. It is resistance tailored in wool. It is a mirror of the mind, cut on the bias of revolution.

From the very first room, the exhibition makes its thesis known: that Black fashion has never merely followed trends, but has carved its own contours—often under duress, often at great cost, and always with astonishing beauty. The viewer is ushered into a historic continuum of self-fashioned dignity: from Julius Soubise, the once-enslaved Caribbean dandy who scandalized London with his perfume and plumes, to Toussaint L’Ouverture, whose imagined portraits exude a military elegance potent enough to crown a nation.

This is not aestheticism for its own sake. These garments were chosen as shields and as spells.

William and Ellen Craft knew this when they escaped enslavement by donning an audacious disguise—Ellen passing as a white male aristocrat, William as her servant. Their liberation depended not on violence or pleading, but on precise costuming and exquisite poise. They understood what generations of freedom fighters and fashion theorists have come to accept: that the uniform of power can be rewoven by those once stripped bare.

What follows throughout Superfine is a liturgy of tailoring. There is the rakish elegance of Thomas-Alexandre Dumas, the French general of Haitian descent whose portrait radiates both valor and veneration. There are the subtle codes of gender non-conformity worn by Stormé DeLarverie and Ralph Kerwineo, whose suits were declarations of identity in a world that refused their existence. There are portraits of nineteenth-century Black sitters, their gloves immaculate, their gazes unflinching, their presence undeniable.

These moments culminate in the contemporary: the sacred geometry of Grace Wales Bonner’s silhouettes; the democratic cool of Telfar Clemens; the jewel-toned conceptualism of Iké Udé. Each designer extends the legacy with scholarly rigor and aesthetic command, revealing that fashion, when placed in the right hands, becomes a political document—signed not in ink, but in silk, leather, and thread.

To speak of fashion without speaking of art is to sever the body from the soul. Kehinde Wiley paints in the same language that Wales Bonner cuts. Kerry James Marshall renders the same sovereignty that Iké Udé wears. The canvas and the closet converge in a single cry for self-determination.

This is not simply about Blackness. Nor is it simply about style. This is about the elemental force of creativity. This is about the exiled returning robed in light. This is about the alchemical truth that beauty is not frivolous. It is power refined.

The exhibition does not end. It culminates. In a final gallery, a pair of sitters lock eyes with the viewer. Their fashion is impeccable. Their history unspoken. Their message crystalline: we existed. We adorned ourselves. We authored beauty under siege. We dared.

One cannot exit Superfine unchanged. One must reckon with the fact that art, in all its forms—tailored, painted, sculpted, staged—is not a luxury for the elite, but the oldest tool of liberation known to humankind. Art allows us to construct the self the world refuses to imagine. Art allows us to speak when silenced, to dance when shackled, to illuminate when obscured. It is the language of those born beneath empire who still choose to rise.

In this moment, when civilization teeters between enlightenment and erasure, we must guard the citadel of art with holy fervor. We must wear our identities like crowns and carry our creative visions like torches. We must fund, teach, collect, and protect that which makes us not just visible, but sovereign.

Fashion is not shallow. It is a portal. Beauty is not indulgence. It is resistance. Art is not escape. It is evolution.

For those who understand this truth, who crave a life that is not just adorned but defined by purpose and poetry—I will see you where revolution is stitched in silk and history is worn like armor.

Superfine: Tailoring Black Style, on view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through Oct. 26. For more information, visit metmuseum.org.