May is National Treatment Court Month—a time to highlight how treatment courts reduce crime, save taxpayer dollars, and strengthen the safety and well-being of our communities.

Treatment courts work because they offer people a second chance—with structure, support, and accountability. Instead of going to jail, those who plead guilty can enter a treatment program where they commit to staying drug and alcohol free, remaining arrest free, and taking regular drug tests. They also meet often with a specially trained judge who doesn’t just enforce the rules but actively supports them on their journey to recovery. It gives people the support they need to heal, grow, and become active members of society again while holding them accountable.

New York didn’t always embrace treatment courts. To the contrary, the Rockefeller Drug Laws that went into effect in 1973 mandated long prison sentences for most drug offenses. This disproportionately impacted people of color and resulted in 150,000 New Yorkers being incarcerated for non-violent crimes.

Things started to change in 1993, when New York’s first treatment court opened in Midtown Manhattan to address “quality of life” arrests like vandalism, fare evasion, loitering, and drug possession. Known today as the Midtown Community Justice Center, this court was founded upon the concept of restorative justice, where participants engaged in service projects such as painting over graffiti, sweeping the streets, and cleaning local parks, all while being given access to treatment for substance use/mental health disorders, job training, and support for stable housing.

New York’s first adult drug court was founded in Rochester in 1995, quickly followed by drug courts in Buffalo, Syracuse, Brooklyn, and Suffolk County. Today New York has over 90 adult drug treatment courts where teams of local social service providers, treatment providers, and criminal justice professionals work together to formulate substance use treatment plans for their participants. In exchange for a favorable legal outcome, the participants agree to comply with court-ordered conditions, including substance use treatment and random drug testing. The rules and conditions are set forth in a contract entered into by the participant, their defense attorney, the prosecutor, and the court.

The Rockefeller Drug Laws were rescinded in 2009. Now, under Criminal Procedure Law 216 (also known as the Judicial Diversion Law), designated judges have the authority, without the consent of the prosecutor, to offer a treatment disposition to certain felony offenders with a substance use disorder, and then to reduce or even dismiss the charges upon the successful completion of treatment.

Today we have several types of treatment courts that provide for participants’ specific needs and backgrounds. These include drug courts, mental health courts, veteran’s treatment courts, family treatment courts, impaired driving courts, opioid intervention courts, and emerging adult courts. As a testament to their success, over 1,000 drug-free babies have been born to individuals participating in one of our treatment courts and, in total, we have graduated over 73,000 individuals. Our treatment courts currently have almost 6,000 active participants.

As the newly appointed Statewide Coordinating Judge of Problem-Solving Courts, I’ve had the privilege of visiting treatment courts throughout New York and witnessing their work firsthand. One experience in particular left a lasting impression.

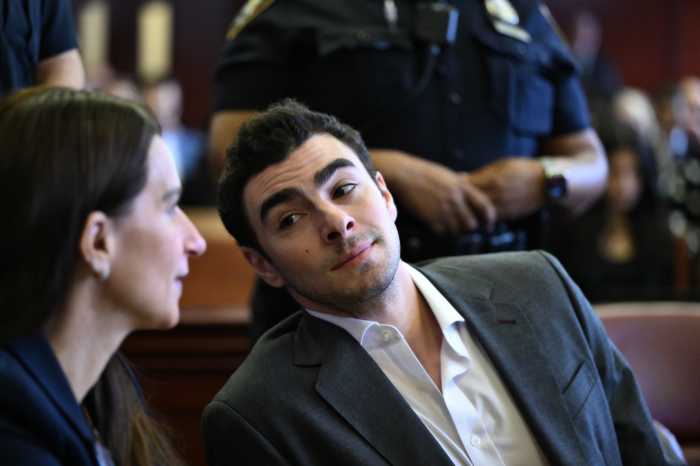

During a visit to a mental health court, I was observing proceedings when the judge unexpectedly called on a young man sitting at the back of the courtroom. I’ll call him John. The judge appeared surprised, noting that John had previously exited the program and was no longer participating in the program1. Still, the judge welcomed him warmly and invited him to the front.

John was visibly upset: His hands shook, and he avoided eye contact. As he spoke, it became clear why he had come to court that day. John had just learned that a close friend had died, possibly by suicide or through a tragic accident. Overwhelmed and grieving, John didn’t turn to substances, lash out, or isolate. Instead, he came to the place where he once found support, telling the judge that the court was “always so nice to him,” and he needed help.

After speaking with the judge, John met with a mental health counselor present in the courtroom. They arranged for him to see his personal counselor later that day. John left with a safety plan and renewed hope. (1 While the judge believed that John had graduated from the program, off the record conversations with the program coordinator clarified that John had unsuccessfully completed the program on an earlier date.)

This single encounter illustrates the heart of what treatment courts do every day. As I have traveled the state, I have witnessed countless individuals whose lives have been positively impacted as a result of their participation in treatment courts. In Manhattan, I witnessed a young man graduate from the program and heard his attorney speak about him and his accomplishments. The attorney commented that he had represented the young man’s father and that his grandfather had also been incarcerated and that when his mother contacted him, the attorney took the case in the hopes that he could find a different resolution for this young man. Because of the treatment court, this young man had a chance which had not been extended to his father or grandfather, and was given a chance to break the cycle. In Staten Island, I heard a young man speak about gaining custody of his three children, something which filled him with pride and hope for his future.

Across the United States, courtrooms are filled with individuals facing the complex challenges of substance use and mental health disorders. Without targeted intervention, many of these individuals remain trapped in a costly cycle of arrest, incarceration, and relapse—burdening law enforcement, straining public resources, and shattering lives.

Treatment courts disrupt that cycle. They hold individuals accountable while providing the support and structure needed to recover and rebuild. Combining treatment with supervision, these courts return people to their communities healthier, more stable, and ready to contribute.

Today, there are roughly 4,000 treatment courts nationwide—including around 340 in New York. Research backs their success: one comprehensive, multi-site study found an average crime reduction of 58% and cost savings exceeding $6,000 per participant. Beyond those figures, treatment courts also drive improvements in education, employment, housing, financial stability, and family reunification.

As we celebrate National Treatment Court Month, let it be a call to action. Let us expand access to these courts and extend their benefits to every community in need.

By changing one person’s life, we create a ripple; by changing many lives, we create a wave.

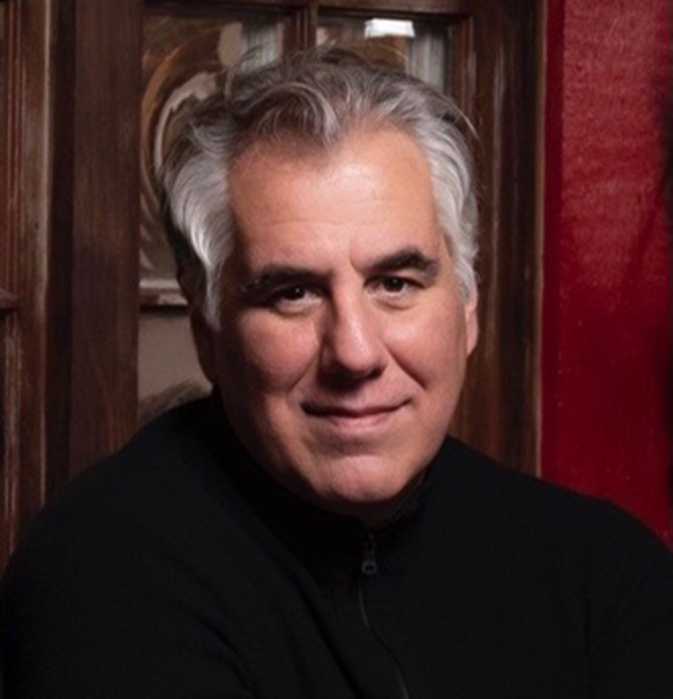

Honorable Debra J. Young was named Statewide Coordinating Judge for problem solving courts in February.