BY MAKINI BRICE, LAUREN YOUNG, MARIA CASPANI AND ANDREW HAY

Mel Solomon loved to sing.

He knew the lyrics to entire Broadway musicals and shared them with his granddaughters Zoe and Madeline during their annual summer visits from Brooklyn, New York, to Kansas City, where he was a renowned architect.

Even after Alzheimer’s Disease stole most of his memory, Mel sang to his newborn grandson Joshua, who was born in 2019, his daughter Laura Solomon recalled. “My father couldn’t really articulate himself well any more, but the music never disappeared,” she said.

Mel, age 83, died of complications from COVID-19 in Roseland, New Jersey on April 22, where he had lived in an assisted living community near his children for the past year. No one in the family got to say goodbye.

“He just vanished,” Laura said.

The global death toll from COVID-19 is approaching 1 million people, and in the last week the number of dead in the United States alone passed 200,000. Out of every 100 people who have been killed by the disease in the United States, around 70 are aged 65 or over.

These staggering statistics mean that families are now missing tens of thousands of grandparents who were alive six months ago. More than 80% of Americans 65 and older have one or more grandchild, Pew Research shows, and two-thirds of those have more than four.

Grandparents often fill a special niche in a child’s upbringing that is distinct to that of parents, said Alan Schlechter, a child psychiatrist at NYU Langone Health, a New York City hospital. They create a rich history for their families, connecting them to other countries, traditions and hobbies, Schlechter said, as well as providing childcare and financial support.

From grandparents, children learn about resilience by hearing tales of the things their elders overcame, he said, and often receive a level of “unconditional love” they don’t get from parents.

Grandma’s boy

Otis Redhouse’s grandmother Yazzie Redhouse taught him how to heal a cut with pine sap, drive a sheep herd to where the rains fell, and speak the Navajo language.

“They were the keepers of the ranching and sheep rearing traditions,” said Redhouse, 40, of Yazzie, 85, and grandfather Lee Redhouse, 87. The couple lived on the Navajo Nation, the largest Native American reservation in the United States, which straddles parts of Arizona, New Mexico and Utah.

Growing up, Otis lived with Yazzie and Lee for several months, while his mother went to look for work in Utah.

He would go to a church and travel to religious revivals with his grandma, he recalled, where they would read the Bible and conduct services in the Navajo language. His grandparents also taught him to shear and butcher a sheep, and make bread.

“I’m a grandma’s boy,” said Redhouse.

Yazzie and Lee both died from COVID-19, along with his aunt, within five days of each other in April, he said. They left behind more than 170 grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Life of the party

Celina Boullosa, or “Yeya,” as she was called by her five grandchildren, came to the United States from her native Argentina in 1971, and taught herself English by watching cartoons with her daughter.

She made a living sewing, cleaning and cooking, in Toms River, New Jersey, and loved to dance bachata, salsa and merengue with her friends, a passion she passed along to her two granddaughters.

“My mom was the life of the party everywhere she went,” her daughter, Mary Ann Lear, recalled. “She was very feisty, very assertive and, even with her broken English, she made her point.”

Boullosa really could cook, her family recalls. Rice and beans was a family favorite, as was garlic shrimp and her empanadas.

The last time her family saw her was in February, for Lear’s birthday, when Boullosa, 71, traveled to North Carolina to visit. Boullosa learned two months later she was sick with COVID-19, and died of cardiac arrest on May 18.

On Boullosa’s birthday in June, Lear made empanadas the way her mother made them. Lear’s own daughter, Brooklyn, 9, helped to roll the dough. “They actually tasted amazing,” Brooklyn said.

My Cherie

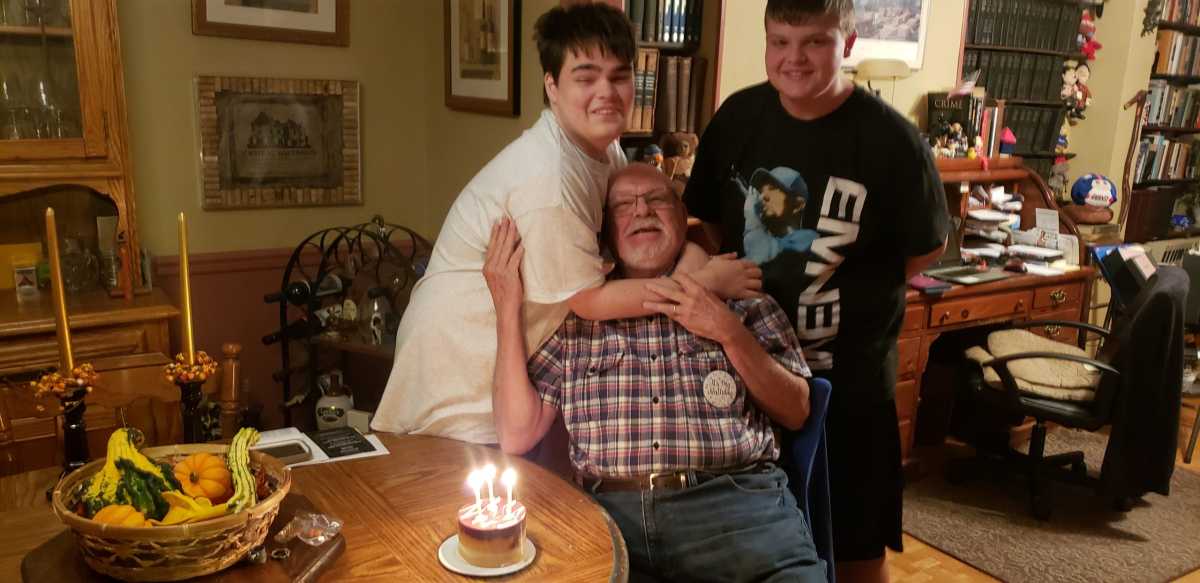

Two months after her youngest granddaughter was born, Cheryl Burch stared at her son and told him, “Your next one will be a boy.”

“And I said, ‘Next one? What are you talking about, next one? I have this one. This one is still a baby,'” her son, Aaron Burch, recalled.

Cheryl Burch lived with her husband in Davison, Michigan. An avid motorcyclist, she was passionate about her work as a fraud examiner, an enthusiastic clarinet player, and avid concert-goer. She particularly liked the Stevie Wonder song “My Cherie Amour,” her son remembers.

She saw her grandchildren weekly, and loved to take them out for lunch and shopping, and “just completely spoil them rotten,” he said. Although she’d followed guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, she became sick and was hospitalized with COVID-19 in April.

In May, she was put on a ventilator – the same day Aaron and his newly pregnant wife learned they were having a boy. When they told her in a Zoom call, she smiled a little, the nurses told her son later.

Cheryl Burch died on June 4.

There’s grandpa with his nose on

John Walter, a lifelong Queens, New York resident, received a congratulatory letter from the state on his 80th birthday for having the same zip code his entire life.

“His big adventure in life was moving from one side of Metropolitan Avenue to the other side,” his son Brian said.

His sense of humor, though, was boundless, Brian recalled. “He would carry around a red rubber nose in his pocket and at the most inappropriate times, without even saying anything, just put it on,” he said. “You’d look over and there’d be Grandpa sitting with his red rubber nose on like nothing was wrong.”

John worked as a historian and author for most of his life. He was especially close to one of Brian’s two young sons, James, 19, who suffers from autism.

John started feeling unwell in April, was diagnosed with COVID-19 in a Mount Sinai hospital, and died 18 days later.

His sudden loss has been “very difficult,” for James, Brian said.

“He just repeats the same things,” he said. “‘Grandpa can’t watch the Giants anymore’, ‘Grandpa is in heaven,’ and ‘We can’t see Grandpa anymore.’… He just cycles through that.”