By JERRY TALLMER

Volume 73, Number 24 | October 15 – 21, 2003

THEATRE

CLOSET CHRONICLES

Ground Floor Theatre

312 W. 11th St.

Thu.-Sun., 8 p.m.

Through Nov. 2

$16.50, 212.352-3101.

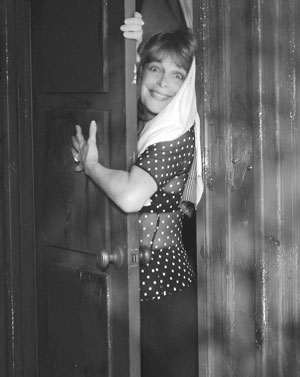

Sokol plays mom of gay son

Just at Thanksgiving dinner, 25-year-old George Angell lobbed a small bomb onto the dining room table.

“Mom, Dad, I’m gay,” he cheerily announced.

His father managed to get out the words: “Pass the potatoes,” before running off to hide in the coat closet.

Now it is Christmas. George has come home again to Cincinnati for the holiday, and George’s mother is, as always, trying to make the best of things.

“This year,” Nancy Angell chirps, as only Marilyn Sokol can chirp it, “we start the tradition of sharing Christmas with our gay son… Makes it sound more festive, doesn’t it?”

“Gives ‘Don we now our gay apparel’ a whole new meaning,” chimes in George’s acerbic 15-year-old kid sister Agatha.

Emilie Madison plays Agatha. Brandon Malone plays George. Richard Leighton plays Ed Angell, George’s dad. Ben Hersey plays Wes, the scroungy lover George brings home for Christmas. And Jason Cicci plays Dr. Neimark, former frozen-yogurt salesman and founder of the Gay-No-More clinic that George attends (briefly) with the gift certificate given by his folks for Christmas.

“Closet Chronicles,” the comedy in which all these people appear, is at the Ground Floor Theatre, an intimate venue in the West Village through November 2. It was written by Eric R. Pfeffinger and directed by Ben Hodges, who has also edited “Forbidden Acts,” a roundup of eight decades of plays centering on homosexuality, to be published by Applause Books in November.

“A comedy with a serious underbelly,” explained Marilyn Sokol. “A real domino construction. If somebody misses a line––oy oy oy,”––this from the Sokol whose stage delectations have ranged from “Me and My Fanny” (i.e., Fanny Brice) to Gertrude, Queen of Denmark (who needs Hamlet?) to Hannah Da Blinde, the blind Cassandra of Herb Gardner’s hard-hitting “Conversations With My Father.”

“In this one, I get to have red hair and everything,” Ms. Sokol said recently, from beneath a great frizzle of non-red hair. “A mother but not a Jewish mother, which is refreshing, and in a way I’ve not had the opportunity in my 38 years in the business. To play a Midwestern and Christian mother, which only happens”––theatrically, she means––“in less commercial environments.”

Downstairs in a brownstone just west of the White Horse Tavern, The Ground Floor Theatre, is hardly a commercial environment.

When the prodigal son walks in the door at Yuletide, his mom greets him with “Hi, George!” while his dad inquires: “Still gay?”

“You betcha,” says George.

“That’s nice,” says mom.

She and George’s father, when they’ve recovered from their initial shock, start wondering if, as she puts it: “Have you ever thought about, y’know?” — going to bed with someone of, well . . .

“Why?” says Ed to Nancy. “Have you?”

“Thought about sex with a man?”

“Thought about sex with a woman?”

“Nooooo,” she says, not too convincingly.

“Nancy!”

“I mean, I don’t think so, not, you know, deliberately. Not in detail. But, I don’t know, I mean, for instance, you know, that Tina Turner is certainly an attractive woman. You know, there’s a real inner strength there, or seems to be, that, well, I just think…”

“I’m Jewish, but I wasn’t raised Jewish,” said the Obie- and Emmy-winning actress who plays Nancy. “I don’t say I’m not Jewish, but I’ve been a practicing Buddhist since 1973… Tina Turner pulled herself up, really, through her Buddhism.”

In Sokol’s Buddhist group “there was a fellow who became blind gradually. I didn’t study him, but as an actor you absorb things. So when the time came for me to do Hannah Da Blinde, I had that inside of me. When I auditioned for Herb [the recently and grievously deceased Herb Gardner], he sent the tape to [director] Dan Sullivan, who didn’t know me from Adam.” Tiny pause. “I was a pretty good blind person.”

One playgoer who, as it happens, thought so, and told her so, was Al Pacino, who won an Oscar for his blind Lieutenant Colonel Frank Slade in “Scent of a Woman.”

Nancy Angell’s temptations toward a lesbian experiment are rather ambiguous, no?

“I don’t think it’s so ambiguous,” said Ms. Sokol. “She may be shy originally. After she begins talking, it becomes obvious that it’s really a fantasy. But what’s also obvious to me is that she and her husband are very much in love. They take this revolutionary experience––the coming-out of their son––take it and enhance their lives. That’s what makes it Jewish––not cold and Waspy, but a Jewish love of children––even if they’re not Jewish.”

Marilyn herself was born in the Bronx but grew up in Washington, D.C., where her mother worked at the State Department’s Agency for International Development, her father was Commissioner of the Bureau of Accounts and, later, an assistant secretary of the treasury.

“Basically I didn’t know what he did, because it was secret work during the Cold War. His building was catty-corner from the White House, and his name was on a plate by the entrance. I was so proud.”

Ms. Sokol’s one-to-one knowledge of people who have come out is a bit limited.

“You know, in the theater it’s so rare for someone to be in the closet. I’m sure there are people of a certain age who didn’t have that opportunity––the opportunity to come out––married people, with a longstanding record of domesticity. You just get the sense that if they’d had the opportunity…

“I do know of one Manhattan family,” she said, “where tremendous acrimony and distance preceded the coming out of their son, a brilliant young man who is now going to be a doctor. How do I know? Just from his demeanor when he talks about it. It’s like Albee. A nightmare.

“On the other hand, I know a Jewish young woman both of whose parents are psychiatrists. Maybe she did come out, or maybe it was just understood. In any event, they’ve given her unquestioning love. As a result of that kind of nurturing, so strong, she herself is a nurturing person, and is now going to be a director.”

Did any of this, Marilyn, feed into your performance as Nancy Angell, or did none of it?

Wrapping her head in her arms, Ms. Sokol gave it some thought.

“All of it,” she finally said. “But I think it was also seeing my parents’ struggle with my going into theater, and with my divorces…”

How many divorces would that be?

“Two and a half,” said the Marilyn Sokol who knocked some of us out a few years ago with her confessional autobiographical “Guilt Without Sex.”

Now she’s in a comedy of another sort, with a voice provided by playwright Pfeffinger, that she thinks is “very original and on a much higher level than most TV sitcoms. In fact I think this play could be turned into a good sitcom for Bravo or HBO.”

And you wouldn’t mind being in it, right?

“No, I surely wouldn’t,” said the oy oy oy shiksa mama of Cincinnati and West 11th Street.

Reader Services