BY RICHARD HAYDEN | The marble steps were just as I remembered. White and elegant, they elevated me and my fellow concertgoers into the foyer beneath the glow of a black chandelier. In the lobby a gorgeous hipster sat behind the information desk shooting us a look that didn’t invite questions. My gaze languished on her tattoos for a moment before I made my way toward the music. Walking through large doors and onto the dancefloor of the Marlin Room — named for the stuffed swordfish hanging above the bar — the sound went from a muffle to a roar. After 16 years I was back at Webster Hall.

In 2000 I worked as a barback at the nightclub, at 125 E. 11th St., for six months. As an awkward 20-year-old photography student from Westchester who was into bands like the Velvet Underground and the Stooges, I longed to escape the suburbs. A hip Downtown life was what I wanted, so when a 6-foot-5 drag queen in a yellow biker jacket greeted me the night I applied, this job seemed like my ticket into the glamorous East Village bohemian scene.

The manager was enthusiastic and hired me on the spot. We soon developed a great rapport. Ten years my senior, he dated one of the club’s dancers and regaled me with stories of his days as a punk hanging out at CBGB’s in the early 1980s. I thought nothing could have been cooler.

The old building was majestic and its history was woven into the fabric of the Village. Built in 1886, it had gone through numerous incarnations that included a speakeasy, a recording studio and a hard-rock venue named The Ritz. In 1992 the space was rechristened Webster Hall and quickly became one of the city’s hot spots. My manager claimed that Leonardo DiCaprio had once been a regular and liked a particular corner of the main room since it afforded him privacy. On slow nights, I dreamed of sneaking up to Leo’s spot with one of the dancers.

In New York’s fickle nightlife scene, it’s hard to stay on top for long. Venues go through a hot period before fading out. In 2000 I thought the place would be like Studio 54 but quickly realized it had lost its sparkle. Far from being a hotbed of celebrity activity, the only famous person I ever saw there was Geraldo Rivera. Barbacks were at the bottom of the totem pole; so instead of dancing through beautiful people to deliver liquor to the bar, most of my time was spent cleaning up messes that drunk revelers left behind. Eighteen-and-over nights were the worst because the underage kids were like baby cobras. Not knowing their limits, they would mix alcohol and ecstasy before coming in and spew vomit as if it was venom. Finding myself covered in stale beer and smelling like an ashtray at the end of each shift, it was anything but the glamorous life that I had imagined.

My biggest complaint was the terrible music. There were four floors — techno, pop, hip hop and salsa. Each had a resident DJ who spun the same set every night. In the Marlin Room, soggy ’80s and ’90s pop songs brought out a crowd that was willing to overpay for a drink as long as they met someone before last call.

Independent acts were almost never booked and it was a waste to see such a magnificent space utilized so uninspiringly. After a summer of watching greasy drunk people fall all over each other, I was over it. I had not hooked up with a single woman, much less one of the club’s dancers. On a hot Friday in August they fired my manager, so I quit right then and there.

I left Webster Hall that evening feeling like I was born too late. The speakeasy, masquerade balls and delirious rock concerts were gone and would seemingly never return. The fading away was complete.

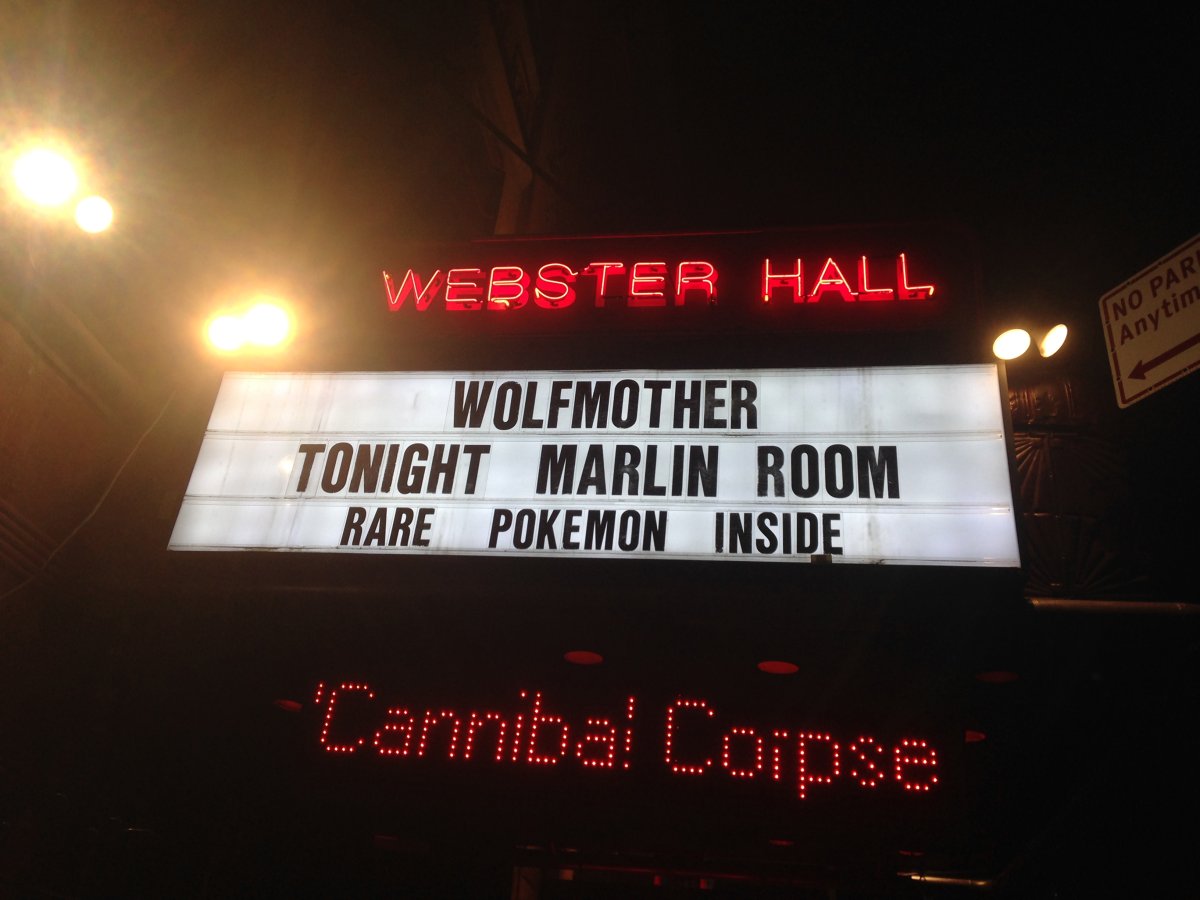

So, now as a married man, college graduate and a Navy veteran living in Queens whose party days were over, it was with great curiosity that I recently went back for a show. Last month, I was there to see Wolfmother, a bluesy Australian rock band that dazzled me at Coachella in 2006.

During my journey up the marble steps, I was struck by how clean everything looked. The ratty, used-up feeling that the place exuded 16 years earlier was gone. The Marlin Room had been fitted with a beautiful new bar and was filled with good-looking people. The adjacent room had been redone, too. Sporting a tiki theme and a mini pizza parlor, this laid-back lounge was a nice counterbalance to the booming noise beside it.

What most impressed me this time, though, was the music. After playing the previous evening with Guns N’ Roses, Wolfmother came out and absolutely destroyed it. Lead singer and guitarist Andrew Stockdale bounced around the stage and manipulated the dance floor with the power of his voice. The crowd was hot and perspiring in the summer heat, but, unlike in 2000, this time we were grinding it out to a band worthy of the space. The sound tickled us in that spot where skin meets sweat, and I let the waves roll me along. It was ecstasy to finally be there and hearing great music. I left the show with a headache for all the right reasons.

The nightclub had come a long way from my days as a barback. The vibes were positive and people were genuinely having a good time. It had evolved beyond the uninspiring meat market that I remember.

In the coming weeks and months, the hip artists Peaches, Cannibal Corpse and Corrine Bailey Rae all had concerts booked, and I was sure they would bring a similar energy. Along with Wolfmother, this eclectic lineup is proof that they have finally hired a booking agent with great taste who recognizes the venue’s potential. The club is now everything that I had wanted it to be when I applied for the job as a 20-year-old kid.

Back then I thought I was born too late for Webster Hall. Now I realized I was born too early.