BY MARINA VILLENEUVE

New York has become the 10th state to allow adopted adults unrestricted access to their original birth certificates, a step that will help some investigate their family histories.

A new law effective Wednesday does away with restrictions dating back to the 1930s that required an adoptee to seek a hard-to-get court order to access original birth records.

Those rules had originally been intended to protect the privacy of parents who relinquished their children. But attitudes about the rights of adopted individuals have shifted, while social media and DNA technology have made it easier for long-separated relatives to connect.

Restrictions in New York and nationwide dated back to a time when many women were coerced or shamed into giving up their babies, according to Joyce Bahr, who gave up her son for adoption in 1966 and now serves as president of the New York Statewide Adoption Reform’s Unsealed Initiative, which pushed for New York’s law.

“Times were different and we were also led to believe our children would go off and live happily ever after, which was a little far-fetched concept,” she said. Bahr ended up reuniting with her biological son, Ed, when she relocated to New York. She said the two “loved each other right away.”

“I can understand that there are some birth mothers who don’t want to be found,” Bahr said.

Some Catholic groups, adoption agencies, and some birth mothers and adoptive parents, had opposed lifting the privacy restrictions over fear about traumatizing people — including survivors of rape and incest — who had given up their children.

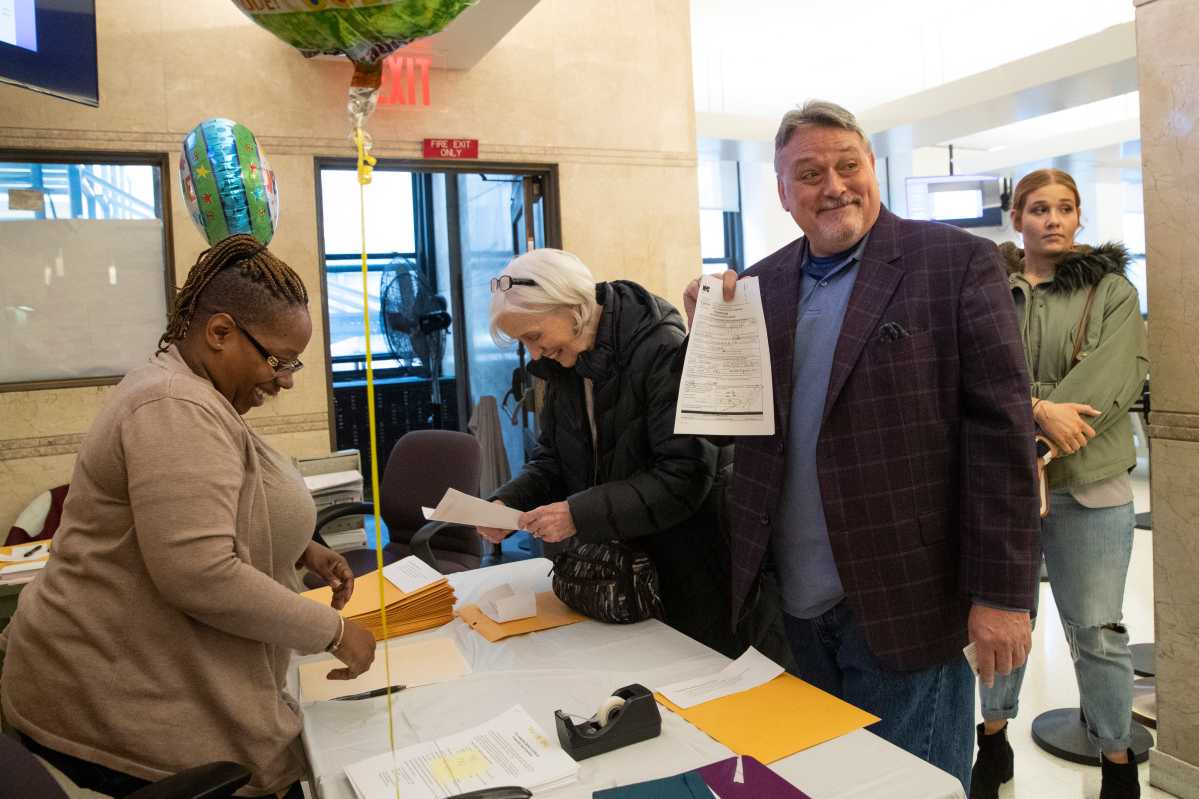

Staten Island resident Joe Pessalano, 58, is one of roughly 600,000 New Yorkers who advocates have estimated will be able to access their birth certificates starting Wednesday.

“It’s validation of my existence to actually see the certificate that has my original information on it,” he said.

When he was 21, Joe’s parents told him he was adopted as a 7-month-old infant in Long Island.

They gave him a piece of paper known as an adoption decree, which happened to include his birth name: Christopher Anthony Ray. It’s an important detail — often found on birth certificates — that gave him an edge over others in searching for birth parents.

Pessalono said without knowing his birth name, he would have never been able to start a search that led him to his birth father, cousins and uncles.

“I would have waited until now,” he said. “And I would have missed out on a wonderful father.”

He ended up finding his birth parents in Greenwich Village, where he had worked for several years as a paramedic. He discovered that his mother was baptized in a church on Christopher Street, while his father worked at a deli Pessalono had frequented.

“When I met him, oddly enough I looked at him and thought, ‘Gee he looks so familiar,’” Pessalono said. “I realized he worked in this deli. He worked there and would serve me my breakfast in the morning. I would remember him walking his dog in the street. It was so weird. It was so surreal.”

Pessalono said he’s seen his birth mother only a handful of times since their first meeting in 1993. He said she’s had a harder time accepting him — in contrast to his birth father, whom he met in 1990 and has since died.

“He was just amazing, he accepted me,” Pessalono said. “I look for acceptance, I always want to be accepted.”

Pessalono, who lobbied for similar legislation in New Jersey, said he’s accepted his birth mother’s perspective: “It’s unfortunate, but that’s what she wanted. I’m OK with it.”

Greg Luce, attorney and founder of the Adoptee Rights Law Center, based in Minnesota, said it was rare for New York courts to grant access to birth certificates, with exceptions being made occasionally in cases involving people with potentially genetic medical issues, or individuals seeking help with citizenship questions.

“It really was one of the top five most restrictive states in the country and had been that way since 1936,” Luce said.

Concerns about privacy and confidentiality have long fueled opposition from groups including the National Council for Adoption, an adoption advocacy group first founded in 1980 in part to fight adoptees’ access to birth records.

But president Chuck Johnson said the group’s perspective has evolved as a growing body of research suggests the vast majority of women who place their children for adoption are open to reunions.

“As states have looked at laws to accommodate the majority, we’ve just asked folks to really take into account the wishes of the women who wish to maintain their privacy,” Johnson said.

In New Jersey, a law allowed adult adoptees to request access to birth records starting in 2017. Birth parents had until the end of 2016 to redact information from their birth certificate.

Meanwhile, groups advocating for adoptee rights hope to fight similar legislation this year in West Virginia. They also hope to pass laws like New York’s in Connecticut, Massachusetts and Maryland.

Johnson cautioned that individuals who are searching should be aware that birth parents might not be ready to meet them, at least at first. He said professional mediators can help navigate reunions.

“Hopefully people will find exactly what they’re searching for,” Johnson said.