TALKING POINT

BY CHAD MARLOW | It was the story that broke the hearts of all New Yorkers. Just a few short weeks ago, Nathan and Raizy Glauber, both just 21 years old, were in a livery cab riding to the hospital where, perhaps, they would deliver their first child. They never made it. A BMW driving at excessive speed crashed into their car killing both young parents. The baby was born within hours and died the next day. Speed kills. Indeed.

Elected and appointed officials from across the city, seeking a constructive way to respond to such a senseless tragedy, rallied behind a proposal to install speed cameras in select locations throughout the city, especially near schools. Unfortunately, because New York City cannot blow its nose without permission from the Legislature in Albany, we lacked authority to enact this safety measure unilaterally. And guess what happened? Our request was denied because certain influential Upstate legislators did not want to risk creating a precedent that could bring speed cameras to their own districts (where they might get caught speeding), and two Brooklyn state Senators cared more about currying favor with the police union than saving lives.

Fortunately, notwithstanding Albany’s obstructionism, New York City’s progressive Department of Transportation has implemented numerous programs that do not require Albany’s sign-off to protect pedestrians, cyclists and other motor vehicles from those traveling at excessive speeds. One such program allows for the implementation of “slow zones” in select neighborhoods. The slow zone program, in short, takes a well-defined, relatively compact area, and reduces its speed limit from 30 miles per hour to 20 miles per hour, with further reductions to 15 miles per hour near schools. These newly reduced speed limits are then promoted and enforced through the use of traffic calming measures, such as specialized signage at zone entry points, painted speed limit information on streets and the selective use of speed humps (relatively flat, elongated speed bumps that are designed to be traversed at 15 to 20 miles per hour).

An analysis by Transportation Alternatives, culled from New York State Department of Motor Vehicles data.

It is hard to overstate the value of a slow zone’s speed reduction: A pedestrian who is struck by a car going 30 miles per hour has a 45 percent chance of being seriously injured or killed, but if the car’s speed is 20 miles per hour, the chance of serious injury or death drops to just 5 percent. Additionally, such a speed reduction reduces the risk of child pedestrian/cyclist accidents by 67 percent. It is, therefore, not surprising that similar programs have produced dramatic results. In London, a 9-mile-per-hour reduction in average slow zone traffic speeds resulted in a 46 percent reduction in fatal and severe injury crashes compared to non-slow zones. In the Netherlands, slow zones resulted in a 25 percent average decrease in injuries. In Barcelona, crash rates in newly created slow zones dropped by 27 percent.

The success of these programs led other cities to implement similar programs, including Berlin, Zurich, Dublin, Stockholm, Helsinki and New York. Beyond their positive effect on health and safety, slow zones also bring numerous quality-of-life improvements, such as reducing traffic noise, reducing cut-through traffic volume (and its related air pollution) and creating more social streets.

Because D.O.T. will not implement a slow zone where its benefits are offset by negative externalities, such as increasing traffic congestion or restricting the flow of emergency services, many areas are not well-suited to receive the gift of a slow zone. Fortunately, one area within the district I represent as a member of Community Board 3 — and in which I have a special interest as founder of the Tompkins Square Park & Playground Parents’ Association (TSP3A) — meets or exceeds all of D.O.T.’s standards for the implementation of a new slow zone. In fact, if established, it would be the new gold standard for New York City slow zones.

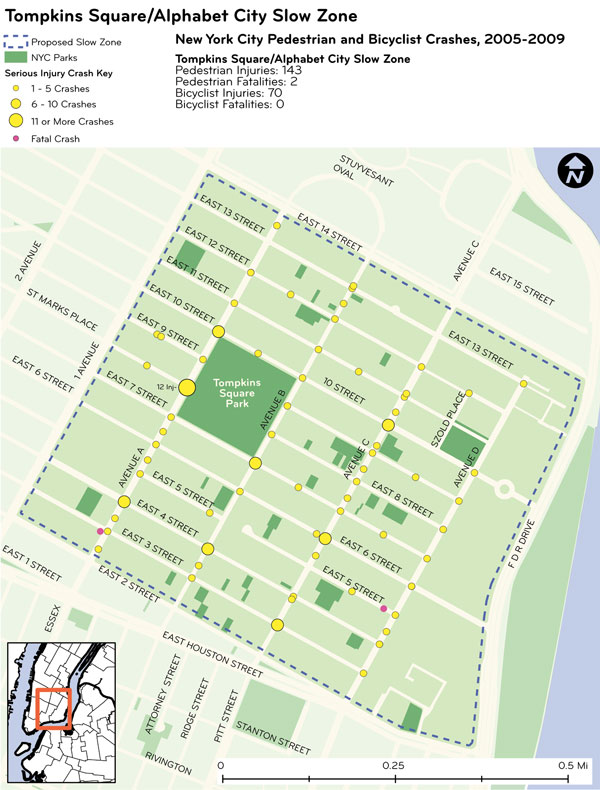

To that end, I am pleased to announce TSP3A will soon be submitting an application to D.O.T. for what we are calling the “Tompkins Square/Alphabet City Slow Zone” (TSACSZ). The proposed borders of the zone (which themselves are not part of the zone) are as follows: the western border is First Ave.; the eastern border is the F.D.R. Drive; the northern border is 14th St.; and the southern border — which, following D.O.T. rules, is drawn to avoid having a firehouse in the zone — is Second St. to the west of where it meets Houston Street, and Houston Street to the east of where it meets Second St.

TSP3A believes the proposed TSACSZ will benefit our neighborhood’s residents, visitors and businesses. With respect to our residents and visitors, the zone will create a safer, cleaner neighborhood with less traffic noise. The improvements will be of particular benefit to children, senior citizens and certain physically challenged persons for whom speeding traffic presents the greatest danger.

Local businesses will benefit in two ways. First, when motor vehicles pass through a neighborhood more slowly, their passengers are more likely to notice and patronize its local businesses. Second, reduced traffic speeds offer increased protection to the patrons of local businesses. Despite what we may think of the noisy, drunken masses that teem out of our local bars late at night, no one wants to see an intoxicated person stumble into a street and get hit by a speeding car. For bars — which can be subject to “dram shop law” civil liability in such cases — the extra safety that slow zones provide should be enthusiastically welcomed.

As noted, the TSACSZ abundantly satisfies all of D.O.T.’s major slow zone approval requirements. For example, D.O.T. requires that slow zones have strong borders. The proposed TSACSZ has a major avenue, highway and crosstown thoroughfare as three of its borders, and a major crosstown thoroughfare as part of its fourth. One significant benefit D.O.T. looks for in a slow zone is that it protects school children. The proposed TSACSZ is home to 12 schools located within seven school buildings, so its beneficial impact in this area would be significant. In fact, the highest concentration of schools in an existing zone — the New Brighton/St. George Slow Zone — is five schools.

Likewise, D.O.T. favors slow zones that help protect kids in preschools and daycare centers. TSACSZ has 22 combined preschools and daycare centers, which is more than double that of the Corona Slow Zone, the existing zone with the highest preschool/daycare center concentration.

The proposed TSACSZ is also home to three senior centers and 38 parks, which attract sizable populations that would greatly benefit from a slow zone’s traffic calming measures.

Moreover, TSACSZ avoids virtually all of the negative factors that count against slow zone applications, insofar as it has no firehouses, hospitals, truck routes or major thoroughfares within its borders.

Finally, the proposed TSACSZ encompasses 0.38 square miles, just 0.08 square miles more than the Elmhurst Slow Zone, whose size D.O.T. calls “ideal.”

Perhaps the strongest factor weighing in favor of the TSACSZ is that the area is particularly dangerous. According to Transportation Alternatives, from 2005 to 2009 (the five most recent years for which State Department of Motor Vehicles data is available), there were 143 pedestrian injuries and 70 cyclist injuries in the proposed TSACSZ. There were also two pedestrian fatalities. That means the proposed TSACSZ averages 42.6 injuries and 0.4 deaths annually. By way of comparison, only one existing slow zone — Elmhurst, with an average of 44.6 annual injuries — is even in the same ballpark as the proposed TSACSZ. The next highest injury total for an existing slow zone is Boerum Hill, which has 28.2 annually. In fact, one existing slow zone, Dongan Hills, was approved by D.O.T. despite having just 4.6 annual injuries — 89.2 percent less than the proposed TSACSZ.

Although, as the above data demonstrate, the proposed TSACSZ is ideally suited for D.O.T. approval, no slow zone application can be successful without demonstrated support from the local community and its elected officials. Although I will personally reach out to key stakeholders in our community to encourage their support, any person, business or organization that wishes to lend a hand to this health and lifesaving effort should contact me by e-mail at TSP3A@yahoo.com. Time is of the essence with respect to this application: The deadline for submissions is May 31, and with a new mayoral administration coming this January, there are no guarantees a slow zone program will exist in 2014.

In the interest of full disclosure, I feel it is important to conclude by explaining why protecting pedestrians from dangerously operated vehicles is so important and personal for me. When I was 23 years old, my father was struck and nearly killed by a speeding drunk driver. The accident left him bedridden, with quadriplegia and a severe brain injury, until he passed away 13 years later, just 16 days after my first child was born. The events of that terrible day — December 5, 1995 — completely devastated my family and me, and the relentless physical and emotional suffering and financial struggles that followed took an enormous toll on us for years to follow.

Having endured such an agonizing experience, I would do anything to help other families avoid a similar tragedy, but I cannot do it alone. This effort cannot succeed without strong, public support from the residential and business communities of the East Village and Community Board 3.

So I am asking the readers of this talking point to please join me and TSP3A in our effort to protect the health and lives of our families, friends and neighbors through the implementation of the Tompkins Square/Alphabet City Slow Zone. Every voice counts. I hope we can count on yours.

Marlow is founder of Tompkins Square Park & Playgrounds Parents’ Association and a member of Community Board 3, where he serves on the Transportation and Public Safety Committee