BY JOSH ROGERS |

The city perhaps is hoping that numbers do lie since recent Census numbers show Lower Manhattan’s well-chronicled population surge is even more dramatic than previously thought when you look at the boom in babies and toddlers — a group that looks to be a few years away from longer school waiting lists.

“We knew these trends were happening but this is the first time we’ve had detailed data,” said Community Board 1’s Diana Switaj, who used block by block Census numbers to calculate the children’s population growth in each of Lower Manhattan neighborhoods.

The numbers even surprised Eric Greenleaf, a business professor at New York University who has been calculating Lower Manhattan’s growing school seat needs for years.

“If you take a look at these gross figures, they are absolutely astounding,” Greenleaf said.

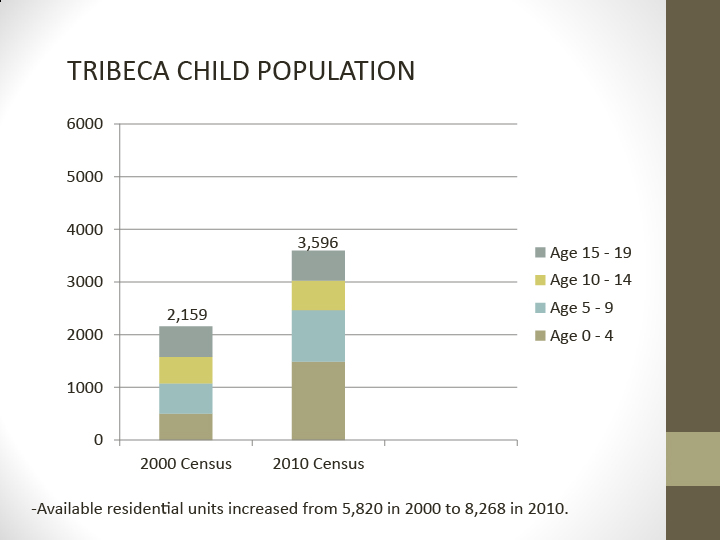

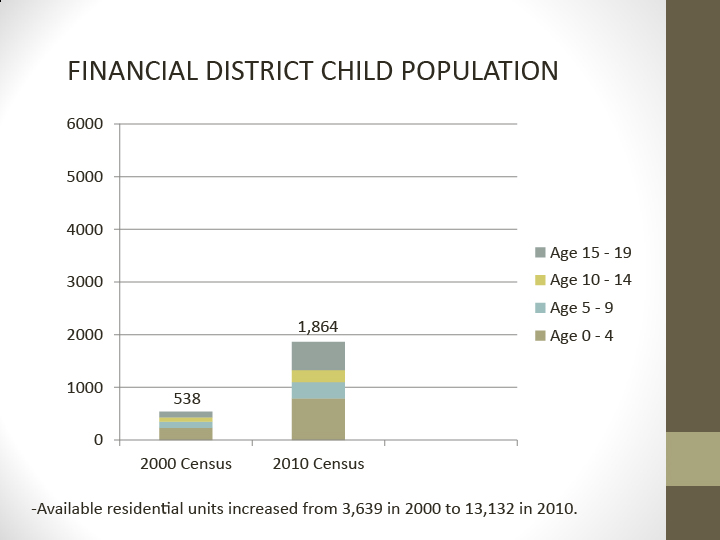

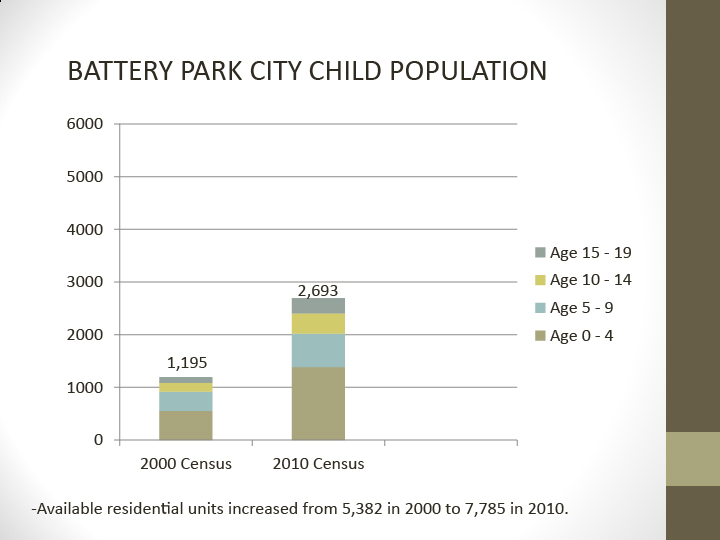

There was large growth in the Downtown childhood population across most neighborhoods and age groups, but the most dramatic increases between 2000 and 2010 were in the 4 and under category.

The Financial District and Tribeca roughly tripled their youngest populations with a 242% increase in FiDi and a 196% in Tribeca, according to the C.B. 1 analysis.

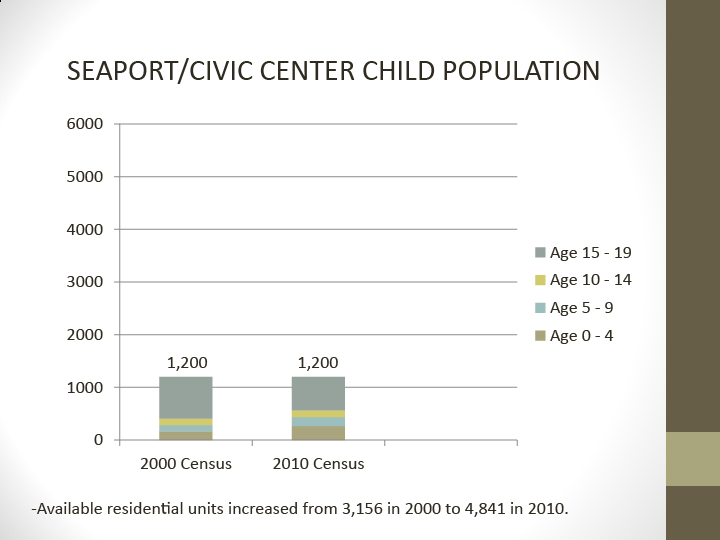

Battery Park City saw an increase of about 150% in ages 0 – 4 over 10 years. Even the Seaport/Civic Center area, which showed zero growth in the overall underage population, still had a 57% hike among the pre-school set.

In the four neighborhood’s, Lower Manhattan’s population of 4 and unders came close to tripling, from 1,459 to 3,931, for an increase of about 170% from 2000 to 2010.

Greenleaf, the NY.U. professor and parent advocate, said the new report may increase his estimate that Lower Manhattan will need an additional1,200 elementary school seats in just a few years.

The Dept. of Education has maintained that Downtown’s newer schools — Peck Slip, P.S. 276 and Spruce Street — will be enough to meet the growing demand.

This year, four out of the five zoned elementary schools in Lower Manhattan have waiting lists.

Greenleaf, said the waiting lists are “so predictable” if you consider things like whether new development projects have many or few large apartments.

He said because the city also groups distinct neighborhoods like Tribeca and the Village, it can make it look like the need for school space is less than it actually is.

“The Dept. of Education adamantly refuses to forecast at the neighborhood level,” he said. “I think they don’t because they don’t want to see what they’d find…

“The city spends billions and billions encouraging development in Lower Manhattan. If you’re going to encourage development you have to plan for the infrastructure that will be needed.”

Greenleaf is not overstating the public investment in Downtown development.

The 9/11 recovery program alone included $1.6 billion in tax-free Liberty Bonds for residential development, and about $300 million in incentives for residents to stay or move to Lower Manhattan.

This week the Dept. of Ed did not say whether it was giving any thought to looking at individual neighborhoods for school need projections, or considering the size of planned apartments.

“Our projections are based on a variety of complex analyses that incorporate a wide range of data,” Devon Puglia, an agency spokesperson, said in a prepared statement to Downtown Express. “We’re working extremely hard to develop great new schools in areas that have seen population growth, and we continue to work closely with these communities in that effort.”

Julie Menin, the former chairperson of C.B. 1, said, “We’ve been saying for years that the problem with the population analysis by the Dept. of Education is it is not detailed enough.”

Menin, a candidate for borough president, was not involved in the C.B. 1 report, but coincidentally she released her own proposal last week calling for a formal review of the borough-wide and community-wide needs for key areas like schools, parks and affordable housing.

She said by studying and identifying each community’s needs before big projects are proposed, it will create more public pressure to get the most pressing needs met.

“Rather than react when developers proposed something, we need to proactively look at what the community needs are,” she said.

C.B.1’s Census analysis points to other needs as well.

When St. Vincent’s Hospital closed in the Village three years ago, Board 1 also raised objections because the closest hospital, New York Downtown Hospital, does not have a pediatrician in its emergency room. The new numbers and the recent takeover of the hospital by New York-Presbyterian might prompt a new look at the issue.