BY STACEY COBURN

A close-up look at life inside a New York classroom

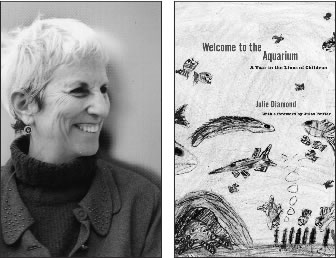

Welcome to the Aquarium: A Year in the Lives of Children

The New Press; 292 pp.; $26

When I was five, and we were lined up to head out to recess, I found out my best friend had made plans to play with someone else. I felt betrayed. Then I felt angry. That’s the same way I felt on the hundredth page of veteran kindergarten teacher Julie Diamond’s first book, “Welcome to the Aquarium: A Year in the Lives of Children.”

This is the point at which Diamond explains she does not teach her students to read.

I should have seen it coming, as the previous chapter outlined Diamond’s rationale for discarding standards, which are the measurable goals states set for each grade level.

Diamond teaches at P.S. 87 in the Bronx, and taught at Bank Street School for Children, a progressive private school (as well as a college for education). Her philosophy is that the curriculum should come from the kids. Diamond is driven to develop children’s confidence, critical thinking skills and ability to socialize.

I identified with her aims, even if I’d been unsuccessful at reaching them myself during my own two-year stint in education. I finished my commitment to Teach For America in Phoenix, Arizona, where I taught fourth grade, in June and some of my failings still haunt me. I related to Diamond’s uncertainty about her own motives and choices, and respected that she continued to question herself after keeping at it for 25 years. Portions of the book are excerpts from her journal, and the entire tone of her memoir is reflective.

As a former teacher, I was also struck by Diamond’s descriptions of handing the power over to the students, allowing them to create signs and posters throughout the classroom — she abhors the “teacher store” kind. She even lets them formulate the routines, the backbone of an elementary classroom.

I’d been nearly brought to tears by the chapter on art — envious of Diamond’s ability to enable students to explore the art materials freely and work on projects until they felt they were finished, not when a buzzer rang and indicated it was time for math.

Later in the book, she dedicates an entire chapter to the social development of a student named Henry. She maintains that art was his link to his peers. He’s the one who creates the sign that reads, “Welcome to the Aquarium,” which serves both as a title for the book, and a metaphor for Diamond’s classroom, a place where children are allowed to be themselves, but in a controlled environment.

She describes her students doing “food color experiments,” where they made equations such as “2 blue plus 3 red” and saved the results on coffee filters. Art is incorporated in nearly every unit the class studies throughout the year Diamond captures in her book. Students make models of the underwater creatures they study and other animals they observe. She introduces more materials throughout the year, and lets the students’ initiative drive projects.

In my classroom, this open-endedness would have led not only to behavior chaos — a mess, some fights — but possibly even a letter in my file, since it would have been seen as “a waste of instructional time.” Believe it or not, markers are outlawed in the middle school where I taught. The rationale was that students steal markers to write graffiti on the walls.

This kind of institutionalization of schools, where children are seen as test scores rather than developing beings, is what Diamond argues against. As I read, I did think, “This is the kind of teacher I wanted to be, before I went through all the trainings,” but to not teach children to read! In kindergarten! I felt she’d crossed a line.

I thought back to my former students, who still guessed words based on the first letter and relied on pictures to figure out what a story was about. They’re twice a kindergartner’s age, and still don’t know how to read. I spent time before and after school teaching students basic letter and sound relationships. I’ve long thought that if I ever go back to teaching, it will be to teach kindergarten, where I could teach students basic reading skills at the age their supposed to learn them.

To be fair, she did teach her students some decoding skills and common words, and read aloud often. But this is not enough to empower students to read independently, which Diamond herself admits.

I was a result of the current trend in education, which is about coverage versus depth, and encourages strategies be modeled and defined by the teacher. Schools today look like one-room school houses, with desks in rows facing forward. Rather than allow students to explain their own thinking, I was encouraged to explain to students how to think. I gave focused lessons on habits good readers naturally employ, like making connections.

When I saw the examples Diamond gave of her students’ conversations and story-telling, I could see how her methods brought her students to high levels of thinking. For example, Diamond describes a student named Amina who struggled for weeks to write about caves. This is what she came up with on her own: “Caves have darkness. Caves have spookiness. Caves have water. Caves have moss. Caves have buckets.” The story has a poetry about it that students are rarely given the time to create.

Diamond’s educational philosophy runs directly against the current today. She writes about this and says it strengthens her resolve. Although I felt uneasy about some of her ideas, reading her book — which is so heartfelt and thoughtful — I was happy she’d been able to cultivate lives apart from the rest in her aquarium.

Julie Diamond, joined by cartoonist Jules Feiffer, will be reading from her book on Thursday, Jan. 22 at 6 p.m. Barnes & Noble (2289 Broadway at 82nd St.)