By KRISTINA PETERSON

New York’s only gay and lesbian country-western dance team

Big Apple Ranch at the Dance Manhattan Studio

39 West 19th Street, 5th floor

(212) 358-5752,

contact@bigappleranch.com

On a recent Tuesday night at the Ripley-Grier Dance studios in Chelsea, five men in dark wash blue jeans cat-walked across the hardwood floor. Sugarland’s “Everyday America” played on the stereo while the dancers rehearsed a routine that swerved between country and coquettish. Several times the men, their backs to an invisible audience, glanced back saucily over their shoulders. A red velvet curtain strategically covered the mirrored wall, blocking the dancers from any indulgent self-reflection.

“We’re past the mirror stage because we just had a performance and they watch themselves,” said Jon Lee, artistic director and choreographer of the Manhattan Prairie Dogs, currently the city’s only gay and lesbian country-western dance team. In November, the group will celebrate its 15th anniversary.

Lee, who owns only to being “over 40,” has gently curling blond hair with a sliver of a blond goatee and a soft, feathery voice. To the rehearsal he wore a red plaid shirt, blue jeans and a small gold hoop earring in his left ear. When the men finished a run-through of the number, Lee led them through a new bow, one that included peering over a pair of pantomime sunglasses. The men discussed what to do in case someone loses balance.

“If you’re going to be like Kyle and fall, fall and run. The MC was like ‘and now the sprint back!’” Lee said, laughing over an incident where a dancer’s exit and return had been noticed by the competition’s announcer.

There was some discussion of choreographing a new number. One dancer asked if the group needed a fresh routine for the upcoming Boots, Bras and Boxers dance, but Lee gently nixed the idea.

“We usually do a number we know and just drop our pants,” he said.

From nine to five, Monday through Friday, Lee works in buildings operations at a Section 8 housing complex. He is single and lives in Chelsea with his cat, Marvin, a pet who receives the attention generally accorded to preschoolers. Recently Marvin began allergy shots because he has a tendency to lick his hair off.

“He would lick the first layer of skin off,” said Lee, who took Marvin to a specialist who advised the shots. “At least you can pet him now.”

Several times each week, Lee sees his sister, Cheryl, who has attended and photographed nearly every New York performance in the Prairie Dogs’ 15-year-history.

“He likes to scrapbook,” she said. “I’m a scrap booker too, but he and I have very different styles.” She paused. “We have very different lifestyles too.”

Lee grew up in Grand Rapids, Michigan and has no formal dance training. He played the coronet in his high school marching band, but otherwise stayed out of the spotlight.

“I wouldn’t have done anything that would’ve made me stand out. I was too easy a target as it was without doing any of that frou-frou stuff,” he said.

Since 1997 he has taught the two-step and line dancing at the Big Apple Ranch, a weekly country dance party in a Chelsea loft that he co-produces with Susanna Stein. The Prairie Dogs perform on average twice a month at the ranch.

“Big Apple Ranch is kind of like your home and they’re the home team,” said Allen, a Prairie Dog of three years.

But even aside from its resident dance team, the ranch holds a unique position in the constellation of gay dance venues, Lee said.

“Susanna and I say this to each other all the time: we provide a community service, a place for people to dance” he said. “There’s none of the bar stuff that happens in New York, none of the attitude. It’s not about taking people home…It’s not about being a gym god.”

Nor to some extent is the Prairie Dogs dance team about the dancing.

“Actually they don’t dance very much. They mostly just pose right now,” said Stein, a former Prairie Dog herself.

Lee is the only remaining full-time member who has performed with the Prairie Dogs since the group’s inception in November 1993. Originally a group of four men and four women, the group evolved out of a previous team, the Cactus Club Succulents, as a competitive country-western dance troupe that performed partner and line dancing at rodeos and conventions, often winning awards.

Over the years, Lee began broadening the group’s choreography.

“We dance for fun,” said Lee, who once had the group do a Riverdance-style routine. “We get away with murder as much as we can.”

The group just learned what Lee calls “the Asian number,” complete with break-away kimonos and fans, but set to LeAnn Rimes’ country song, “Nothing Better to Do.”

“We do a fan reveal,” pulling out the hidden fans, “and the crowd goes wild. And then later on we whip off our kimonos and the crowd goes kinda wild and we said how come our fans get a bigger response than our skirts?” asked Lee.

“And it’s because they expected the kimonos to come off,” he said. “We have to be more creative these days.”

Among other tricks, the Prairie Dogs have breakaway chaps, rings that flash strobes of neon and white glittery skirts, which, with a well-executed roll, magically transform into the rainbow pride flag. The group almost always wears skirts, a signature element designed to generate attention more than gender bend, Lee said.

“We’re not drag queens,” he said. “We’re not trying to be women – it’s just a gimmick.”

Lee is fully responsible for both the costumes and the choreography, though he accepts suggestions from the dancers on both. Keith Allen called Lee “a lenient dictator.”

“He has a very clear idea of what he wants to do, but if you come up with a move that fits better, he’ll say, ‘that’s a good idea,’” Allen said.

Once, Lee got into an argument with the organizers of the Gay Pride Parade over submitting the group’s lyrics so that they could be signed for deaf audience members. In general, Lee ignores lyrics when designing dances and believes the audience rarely listens to them.

“I said we’re not dancing to lyrics,” Lee told the parade organizers. “I said ‘you think I’m being unreasonable, but you’re trying to tell deaf people what the dance focuses on.’” In the end, he sent the lyrics over on a fax that was “pretty much unreadable.”

On a Saturday night early this fall around 200 men and a sprinkling of women sat cross-legged on the hardwood floors of the Big Apple Ranch, a loft tucked into a building also home to “Nothing Else Matters” Software, Flatiron Karate and campusfood.com.

The Manhattan Prairie Dogs entered the room wearing black boots, black skirts and blue shirts topped by a patterned yoke scattered with iron-on rhinestones. Though the group gets new outfits “as often as we can,” Lee recently retrieved these shirts from his closet. Made from upholstery fabric, the shirts had been banished to a cedar chip garment bag years ago because the rhinestones and drapery prohibited the shirts from being washed and a profound odor set in.

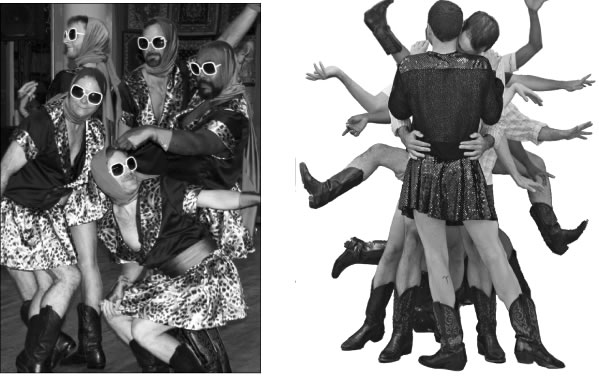

The audience clapped wildly for the Prairie Dogs’ first performance set to Sugarland, then the group exited for a quick costume change. The following group, a mixed-sex performance swing class, elicited polite claps for some of its more difficult technical maneuvers and the house gay and lesbian marching band garnered good-natured cheers. But the audience howled for the final performance of the night from the Prairie Dogs, resplendent in blue scarves twisted Greta Garbo-style around their heads, the pantomime sunglasses translated into actual white, oversize shades. When the men twirled, their leopard print skirts swirled up to reveal matching leopard print briefs.

After the show, spectators flocked to Lee in the lobby, near a small stand where a man shined guests’ cowboy boots.

“We’ve paid a lot more money for a lot less performance,” said Monica Milk.

Lee said the show, a benefit for the marching band, had gone well, aside from a few missteps. “If you didn’t see them, they didn’t happen,” he said.