By MATT HARVEY

Skepticism lives on as New York Review of Books ages but thrives

Back in March, the New York Review of Books moved to the West Village after spending the 45 years since its inception in the West Fifties. “They were kicking us out, we couldn’t get a lease, but look at that,” said Robert Silvers, the 78-year-old founding editor, while admiring the view from the airy new space on Hudson Street. “It’s very nice, we have trees and rooftops,” he added, highlighting the genteel autumnal scene with an offhand gesture.

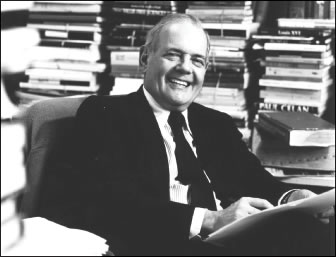

Silvers’s welcoming manner and relaxed, donnish appearance — dark gray cardigan, white shirt, Windsor knot elegantly askew — belies his position as one of the most influential literary editors of the last 50 years. For Silvers, editing – even from his lofty perch as sole monarch of the NYRB – is a quiet craft. The editorial first-person plural is the rule of diction even though it’s obvious that he sets the agenda. (Co-founder Barbara Epstein died last year). “We work seven days a week here,” he grumbled good-naturedly when I complimented him on still being in the office late on a Friday afternoon.

“I really think the Review should stand on the issues, not just me talking,” Silvers told me, pointing at a copy of the 45th Anniversary issue [on newsstands until Nov. 20th]. “It starts with a reminiscence about the man we really admired the most [Edmund Wilson], and ends with Zadie Smith projecting a radical solution for the new novel.” (The celebrated young English novelist calls for a move away from what she calls “lyrical Realism.”) Wilson’s son Reuel cites the diary entries of his father to describe the latter’s marriage to Mary McCarthy. Reuel’s parents’ power as critics is difficult to imagine now (Wilson’s book of essays, Axel’s Castle, was a brought acceptance to T.S. Eliot, for example) were frequent contributors to the Review.

In 1959, Elizabeth Hardwick — wife of poet Robert Lowell — impressed Silvers and Epstein, then editor of the Partisan Review, with an essay that Hardwick published in Harper’s. The piece, entitled “The Decline of Book Reviewing,” turned a scornful eye on the polite, faint praise heaped on books by the Sunday book review supplements of the time, including the august New York Times. “All differences of excellence, of position, of form are blurred by the slumberous acceptance,” Hardwick wrote in the now famous article. Silvers and Epstein began talking about what they could do to remedy the situation.

Four years later, the newspaper strike — and the declining fortunes of the dailies due to the rise of television — gave them a chance to implement their vision. “Jason [Epstein, Barbara’s husband] rang up when I was at Harper’s,” Silvers recalled, “and he said, ‘This is our chance to start a review; the publishers are going crazy. There are no book reviews, but books are still coming out. Everyone’s going to have to buy an ad in the thing.’ ” At the memory Silvers’s patrician stammer dissolved into laughter. Jason Epstein’s — a vice-president at Random House — financial backing was key to the magazine’s launch.

Silvers’s anecdotes about the origins of the NYRB have a well-hewn, practiced quality, but he still can get excited about its storied past. When I mentioned the many intellectual donnybrooks — especially the one between Tom Wolfe and Dwight Macdonald over the fact-challenged “New Journalism” in 1969 — that have erupted across the letters column, his eyes lit up: “Yeah! We’ve had a lot of them, right up until the anniversary issue. We have one this issue too. Steve Weinberg had written an article “Without God,” about living in a world with a loss of faith. We’ve had dozens of letters and they’re still coming in.” I envisioned him rolling up his sleeves and answering every letter himself.

While Silvers was reminiscing about Mary McCarthy’s [first issue, 1963] review of William Burroughs’s controversial, free-associative novel “Naked Lunch,” (McCarthy took exception with Burroughs’s pornographic language while maintaining it had literary merit) a twenty-something assistant in a plaid collar shirt and jeans interrupted to tell us that Obama was giving a press conference. Silvers — who sent Elizabeth Hardwick to a civil rights confrontation in Selma, Alabama, in 1965 — said, “Why don’t we break, what the hell? It’s a historic occasion.”

The old skeptical-liberal man of letters — hunched over his desk alertly — watched the president-elect speaking on television while surrounded by assistants who laughed excitedly throughout the conference. Thickly bound hardcovers, on a wide variety of topics, were piled high around him. Titles included “Who’s Who in America 1993” and “Le Corbusier in England.” Silvers joined in to laugh with his staff once, when Obama made a joke about Nancy Reagan and astrology.

“Well, it was an adept way of saying they haven’t yet quite arrived at anything,” Silvers told me with a shrug after the press conference. But he was enthusiastic about the end of eight years of Bush. I asked him if he, as a self-proclaimed skeptic, was worried that his writers were getting carried away gushing about Obama. “Well,” he said, “Michael Chabon, who covered the Democratic convention for us, gave a sense of the exuberance, but he himself — if you read the thing — had a skeptical quality. He talked about the droning of the speakers. The droning,” Silvers repeated for emphasis.

That Chabon — at 45 — is one of the NYRB’s youngest writers is a sensitive subject for Silvers. “I don’t separate the world into people in their 20s and their 40s,” he said with polite annoyance. But when I asked him whether young writers are having a difficult time developing a unique voice in the age of the Internet he smiled and remarked, “Aha! That’s something you may know more about than I do.” After giving it some more thought, he added, “In all these 45 years writers always have emerged with a special voice, a special perception of their own.” The clear implication was that this was bound to happen again.

In the last two years Silvers has had to deal with the loss of Elizabeth Hardwick (whose “skepticism of convention” he calls the embodiment of the NYRB ethos) and that of co-founder Barbara Epstein. The death of the latter has been particularly trying for him. “We shared everything. We had a way of trying out ideas on each other that was practically a shorthand,” he said. “We saw a lot of the absurdities of the world we’re dealing with. I miss her terribly, but the only thing we can do is carry on and the Review has been going on.”

Seen through the close relationship of Silvers and Epstein, all the acres of weighty prose filed for the paper by famous literary personalities are acts of family friends. Russell Baker, Joseph Llevelyd and Harold Bloom all contributed to the November 6 election issue. Indeed, Silvers called Russell Baker a “great friend of the Review.” Silvers goes on to say it is “a great responsibility” giving his writers assignments, because of the time it takes to craft a piece for the paper. Contributors usually need six weeks for their reviews and sometimes more time. The average article is 3500 to 4000 words. And what of concessions to popular opinion? “We don’t even think about that,” he said gleefully. “What we advance is what we think is interesting.”

Nearly half a century among the chattering classes has taught Silvers that a NYRB subscription is not always renewed lightly. “People say it piles up on the coffee table,” he admitted with a waggish chuckle. “The truth is, there just isn’t enough time,” he added, while urging me to pay special attention to Ian Buruma, on the life of V.S. Naipaul (the Anglophile Trinidadian Nobel prize-winning writer) in the anniversary issue. Then he excused himself to return to editing the next issue — which, unsurprisingly, is chockfull of post-election coverage.