BY Aline Reynolds

Family members, trade unionists, local residents and students gathered at Washington Place in Greenwich Village on Friday, March 25, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Triangle Shirtwaist factory fire, which in a matter of minutes killed 146 immigrant garment workers, most of them young immigrant women.

The poignant, two-hour-long event, held in front of the former Asch Building, engendered grief among the descendants of those who died in the blaze and determination among local union workers to continue lobbying for their pensions and collective bargaining rights. “We’ve come together to remind ourselves why those workers were killed by the greed of their bosses and the inaction of public officials to provide a safe way to exit that building,” said Bruce Raynor, president of Workers United, a North American worker’s union that helped organize the centennial ceremony.

To cheers from the crowd, Raynor continued, “And we come together to remind ourselves that those workers were fighting for their rights to have a union in that workplace, and the right to be treated with dignity and respect on the job – something that’s God-given, in the City of New York and in our country.”

“The Triangle tragedy is a powerful reminder of just how terrible conditions were before unions pushed for basic protections and rights for workers,” said U.S. Congressman Jerrold Nadler – particularly, he said, given the “denigration” and “scapegoating” of organized labor groups taking place today.

The Triangle Factory deaths could have been averted had proper safety mechanisms been in place, pointed out Mary Kay Henry, president of the Service Employees International Union, one of the largest unions in North America. “I feel sorrow, but mostly I feel indignation at the injustice that those women had to jump to their deaths when they could have been saved,” she said.

The workers’ deaths, the speakers stressed, were not in vain. The tragedy, and the pro-union protests that ensued, accelerated the creation of a workplace democracy, according to Sen. Chuck Schumer, and prompted New York State to pass safety legislation that later inspired the New Deal.

“The phoenix that rose out of the ashes of the Triangle Shirtwaist fire was a clarion call to action,” said Schumer. “It supercharged the American labor movement and emboldened activists and lawmakers alike to push forward with workplace safety laws, child labor laws, and most of all collective bargaining rights.”

Safety violations, however, are still occurring around the country and the world since worker’s protection laws are not always strictly enforced. “It’s an ongoing battle,” said Rachel Bernstein, an adjunct history professor at New York University. “The main issue in the clothing industry is that most American manufacturers send [work] overseas to shops where this type of thing occurs,” she said, referencing the fire in a Bangladesh garment factory last December that killed at least 20 workers.

“You can rest assured, folks, that the [U.S.] Department of Labor is back in the enforcement business,” said Hilda Solis, who as a California State Senator in the 1990s uncovered abusive working conditions in a sweatshop in the city of El Monte. “We believe that no workers should be met with abuse or injustice on the job.

“No worker,” Solis continued, “should have to worry about keeping what they earned. And no worker should be afraid they won’t make it home safe at night after their work shift.”

The centennial memorial, she noted, was as much meant as a commemoration of the victims of the 1911 blaze as it was a rally in support of current labor protestors, like those challenging Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker, who is threatening to cut public employees’ collective bargaining rights and benefits in a bill intended to repair the state budget.

“It’s not just for us to look back 100 years ago and say, ‘It was corporate greed that killed these women.’ We have to recognize the corporate greed that we’re seeing against working people today,” said George Gresham, president of 1199SEIU United Healthcare Workers East, alluding to the “Scott Walkers” nationwide.

In remembering the sacrifices the Triangle factory workers made a century ago, the nation must continue to advocate for workers’ rights, especially now that collective bargaining is under attack, according to District One Councilmember Margaret Chin. “Unionized workers are settling for less and less while developers and big business receive million-dollar subsidies. Public workers are taking the blame for budget deficits, while the ‘millionaires’ tax’ sits on the State Senate’s cutting room floor,” she said.

The new generation of workers in Wisconsin and elsewhere, Henry said, is indeed “taking up arms so we can create a country where people can get back to working good jobs, and support a family, and allow us to retire with dignity” — a country, she said, in which workers are able to achieve middle-class status.

Union solidarity and activism are stronger today than ever in recent history, according to Wisconsin Education Association Council president Mary Bell. “Our common commitment to hundreds of thousands of citizens… will not be smothered, it cannot be,” she said. “No matter if it’s 1911 or 2011, the power of the collective voice will triumph over corporate greed.”

“We’ll do whatever is in our power to make sure that every worker has a voice, and every worker has a lending hand,” said Laborers’ Local 79 business manager John Delgado.

Delgado introduced Hector Mena, a union member and former construction worker who said he was denied overtime pay, health care benefits and safe work conditions while working at the Lettire Construction Corporation. He is grateful he is now part of a union, he said, that “fights for their workers and ensures that the workers are treated with dignity.”

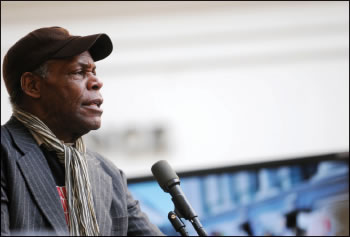

Americans today must take responsibility to improve working conditions for Mena’s generation and the one to follow, according to American actor Danny Glover. “It’s upon us,” he said, “to take this moment as we support those who struggle now to define our world in the 21st century, and to define a new relationship between labor and capitalism.”

“At this moment in our nation’s history, when unions are threatened and the middle class and public service workers are under attack, let this Triangle fire centennial be a call to all of us to rededicate our energies, raise our voices and become more active in the pursuit of justice for all working people,” said Suzanne Bass, representing the descendants of the Triangle victims, many of whom showed up on Friday carrying signs draped with shirts in rememberance of their loved ones.

Bass’ cousin, Lesley Casula, and her family journeyed from Gainesville, Va. to commemorate the life of Casula’s great aunt, Rosie Weiner, who at age 19 died in the Triangle blaze. Weiner’s younger sister and fellow garment worker, 17-year-old Katie Weiner, jumped onto an elevator cable and managed to escape the flames.

Casula has fond childhood memories of spending time with Katie and learning about her experience working in the factory. “[The centennial event] was very emotional and significant to me,” said Casula, who wore a jacket adorned with a photograph of Auntie Rosie. “I wanted to make sure my daughter was there, to make sure [Rosie’s] memories carry on in the family.”

She and other family members in attendance wept as school children from P.S. 1, P.S. 34 and other schoools steadily read aloud the names of the garment workers that perished on that fateful day. Firefighters then ceremonially raised a fire truck ladder to the sixth floor of the former Asch building, which is as far as it could reach in 1911.

N.Y.C. Fire Commissioner Salvatore Cassano compared the Triangle fire to 9/11. “While in many ways, these two catastrophes were very different,” he said, “they caused the nation to do some collective soul-searching.”

The Triangle fire changed forever the way Americans thought of the workplace, he added, and contributed to the creation of the F.D.N.Y.’s Bureau of Fire Prevention and its partnership with the International Ladies Garment Workers Union to prepare employees for emergency evacuations.

In the months following the Triangle Fire, according to Cassano, the city saw its first sudden and substantial drop in daily blazes. “Their deaths made the generation of working Americans — rich and poor, native-born or immigrant — much, much safer,” he said.

Village resident Stephen Kroninger brought his 12-year-old daughter, Rachel, to the event to learn about the fire. The ceremony, Rachel said, drove home the relevance of the memorial to issues plaguing union workers today.

“It was really exciting and sad,” said Rachel. “I learned a lot about the political sense of it – how, if they had gotten a union, [the fire] wouldn’t have happened.”