By Josh Rogers

Perhaps it’s not your grandfather’s neighborhood anymore.

Whether or not the stereotype about Chinatown being filled with passive people too polite to challenge government was ever valid, it’s clear it is not true anymore. Last Thursday night, there were two separate protests on neighborhood issues related to the aftermath of 9/11 — and at a neighborhood workshop organized by the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, frustration and anger were the dominant emotions.

When the L.M.D.C. held similar workshops two weeks ago in the more affluent and predominantly white neighborhoods of Battery Park City and the Financial District, the invited participants seemed happy to view short presentations and break up into small groups to give their thoughts on the best ways to help Downtown recover from the 2001 terror attack.

But at last Thursday’s meeting at P.S. 126, Kevin Rampe, L.M.D.C. president, was interrupted at the beginning by a speaker demanding to know why it took almost two years for the corporation to hold such a forum in Chinatown, which the city estimates lost 10 percent of all the New York City jobs lost after Sept. 11. After several speakers challenged the format of the workshop, the moderator relented and let individuals address the 50 or so participants before everyone broke up into smaller groups. Protesters chanted outside the room and it was the first workshop that required a police presence.

John Wang, president of the Asian American Business Development Center, explained why he interrupted Rampe. “This is two years after,” Wang said while the workshop was proceeding. “That’s why there’s such frustration – because we have been ignored.”

He said there have already been studies done by groups like the Rebuild Chinatown Initiative and that it is time to implement them. The initiative, founded by Asian Americans For Equality, issued a report last year recommending among other things, more economic investment in the neighborhood, the construction of affordable housing, the opening of a neighborhood cultural center and the reopening of streets closed since Sept. 11 for security reasons.

Rampe told Wang that the L.M.D.C., which was set up by Gov. George Pataki to manage Downtown’s rebuilding efforts, was committed to helping Chinatown recover and that it was important to use the money wisely.

“We want to make sure our funding has the greatest economic benefit,” said Rampe. The L.M.D.C., which can fund projects south of Houston St., has about $1billion left to spend on the neighborhoods immediately surrounding the W.T.C. site – Battery Park City, Tribeca and the Financial District – as well as on Chinatown, the Seaport, Lower East Side and Soho.

As he was leaving the meeting, Rampe said he was not surprised to hear the frustration, given that the neighborhood is still recovering. “People are expressing their views,” he said. “It’s great.”

Wang said more things needed to be done now. “Better late than never,” he told a reporter. “But we need speedier action…. The L.M.D.C. needs to put their money where their mouth is.”

Peter Cheng, a former L.M.D.C. employee, said: “I don’t want to say the L.M.D.C. has done nothing. It certainly has done something for this community, but in our opinion it’s not enough. We deserve a lot more help.”

Cheng was the agency’s liaison to Chinatown before leaving a few months ago to head the Indochina Sino-American Community Center. He said wealthier neighborhoods like Tribeca and B.P.C. have been getting too much funding in relation to Chinatown. The $281-million L.M.D.C. residential grant program, intended to encourage people to stay in and move to Lower Manhattan, provides more money per apartment to the neighborhoods closer to the W.T.C. The rationale is that people in those neighborhoods suffered more physical damage, had their apartments littered with toxic W.T.C. dust and experienced more street closures and transportation disruptions in the months that followed the attack.

The development corporation has funded a renovation project in Columbus Park, Chinatown’s largest park, and is currently conducting a neighborhood traffic study. Chris Glaisek, in charge of L.M.D.C.’s off-site planning, said the study is looking at whether Park Row can be reopened and if not, what alternatives can be found.

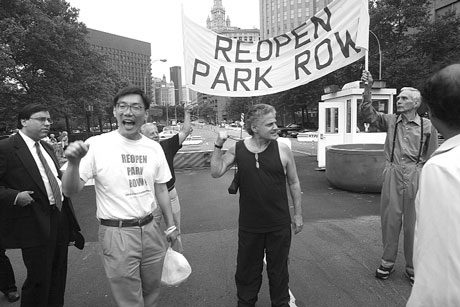

Park Row was the subject of the other protest last week. The New York Police Dept. has blocked the street to pedestrians, city buses and other vehicles since the terror attack to protect police headquarters, although residents have pointed out that the police personnel have taken advantage of the closure to expand the areas in which they park.

The street is the most direct connection between Chinatown and the rest of Lower Manhattan and people at each workshop table last week recommended reopening it to help businesses and residents.

Amy Chin, the executive director of the New York Chinese Cultural Center, summed up the discussion at her workshop table for the audience. “After railing against the process, like good Asians we settled into the process and did what we were supposed to do,” she said.

The group of about eight people at her table thought that the most important needs were quality of life issues such as cleaner streets, jobs, affordable housing, the need for a community cultural center and the reopening of Park Row.

Chin said the other transportation-related recommendations were unpopular at her table. “When we voted down transportation, it was really kind of frustration at our community being ignored.”

May Chen, an organizer of UNITE, the garment workers’ union, said the plans to build large transportation centers at the W.T.C. and at Broadway-Nassau-Fulton St. aren’t close enough to help Chinatown.

The concern about spending too much on the transit centers is shared by some outside the neighborhood. Henry Stern, the former Parks commissioner and the founder of a new civic organization, said two weeks ago that he thought too much attention was being paid to building “elegant stations” rather than new subway and commuter lines into Lower Manhattan.

“Underground palaces created by the alphabet agencies will not necessarily meet the needs of consumers travelers or the riding public,” Stern said. “Do we want every subway station to be Grand Central Station?”

A week after Stern’s comment, the Port Authority and the L.M.D.C. announced that they hired Santiago Calatrava, the world-renowned architect known for his train station designs, to design the W.T.C. PATH and subway station

The day after the L.M.D.C. workshop, Chin, the cultural center director, said she and several others she spoke to felt guilty at attending the invitation-only meeting, particularly since there were protestors outside.

The protestors, who numbered close to 100, objected to an announcement several weeks ago by the governor, mayor, the L.M.D.C. and the Dept. of Housing and Urban Development that they would use $50 million to build 315 apartments for middle-income people in Lower Manhattan. The demonstrators argued the housing should be for low-income tenants and should not be taken out of money left over from the L.M.D.C. grant money, since many people are still waiting to hear if they qualified for the residential grant.

Rampe said no money would be shifted out of the grant fund until every case has been resolved, and if no money is left, the agency will fund the 315 apartments another way..

The protestors chanted near the school window, but by the time they got there, the L.M.D.C. had completed their presentation. The only speakers who were disrupted were Chinatown speakers who had just convinced the L.M.D.C. to allow them to address the entire audience.