By Bonnie Rosenstock

Four hundred years ago, precisely on Sept. 11, 1609, the English explorer Henry Hudson, in the employ of the Dutch East India Company, sailed up the river that would later bear his name, and thus ushered in a landmark chapter in New York City’s history — the 38-year reign of the Dutch colony of New Netherland. (Giovanni da Verrazzano, exploring for the French in 1524, was the first European to see the river, but only belatedly got a bridge named after him.)

Celebrations recently took place all over New York City and New York State during the period of Sept. 8-13 to mark Hudson’s “Voyage of Discovery” and to honor the achievements of the Dutch colony, which lasted from 1626 to 1654, or as Russell Shorto calls it in his extraordinary book of the same title, “The Island at the Center of the World.”

And nowhere was this event more significant than in the East Village’s St. Mark’s Church in the Bowery, 131 E. 10th St. and Second Ave., whose Dutch roots are deep and far-reaching.

“One of the crown jewels,” stated Mary Park, directress general of the Society of Daughters of Holland Dames, in her opening remarks to an overflowing crowd of Dutch dignitaries, Dutch descendants and friends on Fri., Sept. 11, at the church. “This historic site, original farm [“bowery” means “farm” in Dutch] and ultimate resting place of Petrus Stuyvesant, last director of the colony of New Netherland and major figure of the early history of New York City,” she added.

Reverend Winnie Varghese, St. Mark’s priest-in-charge, led a moment of silence to mark the eighth anniversary of Sept. 11, 2001. Then began the two-hour, mid-afternoon homage to Peter Stuyvesant, which included a proclamation, a plaque, a plaquette, poems, history presentations and perspectives, and a planting.

St. Mark’s Historic Landmark Fund, in partnership with the Society of Daughters of Holland Dames and St. Mark’s Church, hosted the event at the behest of the visiting Dutch. Park read a proclamation of the Hudson-Fulton-Champlain Quadricentennial Commission, which welcomed members of the executive board from Stuyvesant’s hometown of Friesland, a province in the north of the Netherlands. The proclamation recognized the work of the Holland Dames, “who are dedicated to perpetuating the memory and promoting the principles and virtues of the Dutch ancestors of its members and erecting commemorative and durable memorials to be a lasting tribute to the early Dutch settlers.”

The organization, founded in 1895, is relatively small compared to other lineage groups and does not have a central headquarters. Forty-five members, scattered across the U.S., attended the event. They were easily recognizable, adorned in Marisol Deluna’s specially designed eye-catching commemorative scarf.

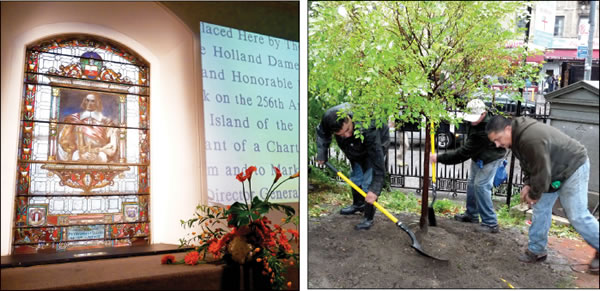

The stained-glass Stuyvesant window, presented by the Holland Dames to the church in 1903, was rededicated. The lost plaque beneath the window has been reproduced and donated by Barbara Andrews Brinkley, the immediate past directress general of the society and a trustee of St. Mark’s Historic Landmark Fund. The plaque’s text, projected on a big screen near the Stuyvesant window, commemorates the 256th anniversary of Stuyvesant’s landing “on the Island of the Manhattans [sic]” in 1647, the 250th anniversary of his grant of a charter to the city of New York Amsterdam and to mark his final resting place.

After losing the colony to the English, Stuyvesant was recalled to Holland. He later petitioned to return to his beloved renamed New York, and died here in 1672. He is entombed in a wall in the St. Mark’s Church east yard. The church sits on the site of Stuyvesant’s family chapel.

Other speakers included Jannewietske De Vries, minister of cultural affairs of the province of Friesland, and historian Dr. Jaap Jacobs, both of whom spoke about Stuyvesant’s controversial and complex character during his 17-year tenure.

“We can admire his leadership and can’t condemn him completely for being intolerant,” stated Jacobs, whose book, “For the Good of the Community: Petrus Stuyvesant and New Amsterdam After September 1655,” has just been published. “It was within the limits of what was possible in his own time. He provided firm leadership, was strong in a crisis and played a crucial role in the 17th-century history of New York,” he added.

Ferd Crone, mayor of Leeuwarden, the capital of Friesland, presented a plaquette to Reverend Varghese with an inscription featuring one of the poetical phrases — that had just been recited by Jelle Kroll in Dutch and Rod Jellema in English — from Stuyvesant to his friend John Farret. The existence of his verse, discovered in a Dutch archive in the 1920s and preserved by Farret, has recently been translated into English and shows a more sensitive, introspective side to the stern governor.

The Frisians gave a Japanese snowbell tree (Styrax japonicus) to the church, which despite the heavy downpour, was planted in the east yard to replace a tree felled in another storm. De Vries said that planting a tree is the symbol of hope, and especially on the anniversary of 9/11, she and her compatriots offered hope and friendship to the city of New York. Unfortunately, the tree died not long after its planting — but it’s the thought that counts.