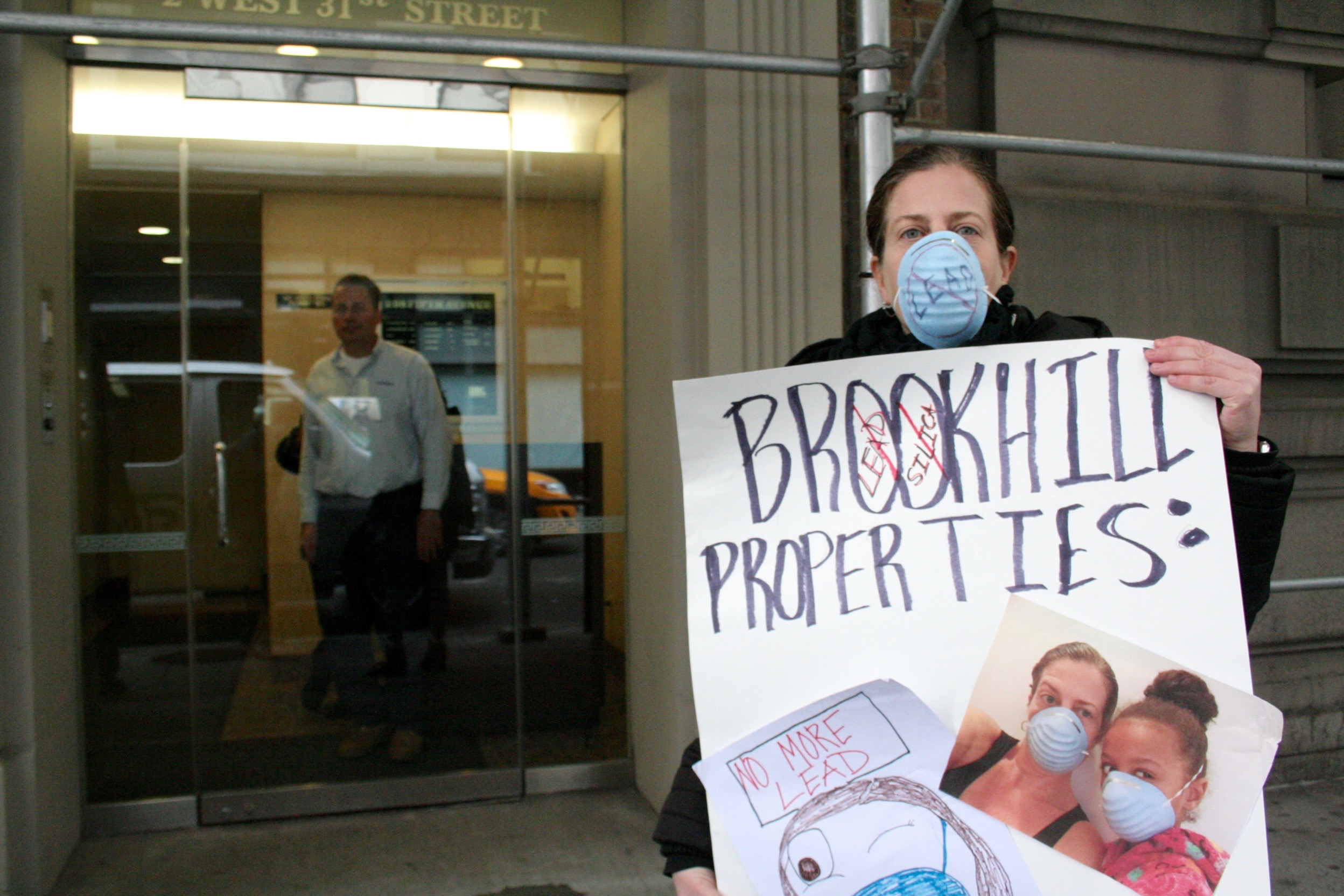

BY REBECCA FIORE | Holly Slayton’s doctor recommended that she and her daughter wear dust masks inside their East Village apartment because of all the lead dust that has accumulated from unsafe construction practices in her building. Slayton and her daughter, Maya Chance, 9, have been living under dangerous conditions for more than two years, with landlords creating unbearable living environments to get rid of tenants, Slayton said.

The tenant said she has had a continuous cough that’s so bad some of the blood vessels under her eyes popped. Her daughter has had upper-respiratory issues due to the lead dust coating the inside of the five-story walk-up, her mother said.

Slayton has lived on the top floor of 514 E. 12th St. for the past 14 years. She used to have a store at 510 E. 12th St., owned by the same landlord, but after 14 years, she was kicked out. She said the storefront is still empty.

The building was formerly owned by Raphael Toledano. Currently, Madison Realty Capital owns it, and construction that the company has led has not been up to code, Slayton charged. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s lead exposure-standard is anything equal to or more than 40 micrograms of lead in dust per square foot on floors, and 250 micrograms of lead dust per square foot on interior windowsills (a high risk area for children).

In some areas of the building, the lead levels were twice the E.P.A. standard, with findings of 82 micrograms of lead in dust per square foot on the floors, according to documents from the city’s Department of Health, provided by Slayton to The Villager.

“They don’t mop up afterward,” she said of the construction workers. “They leave the dust there for a like a week or so and we are breathing that in. Dust was coming up through the floorboards. All five girls in the building were sick.”

She said inspectors from the D.O.H. Healthy Homes unit have visited the building three times. She said only 10 of the 20 units are occupied and only five of the original tenants are left.

“It’s like a bad movie or something,” Slayton said. “But we are rent-stabilized tenants, where else are we going to go? We are living like squatters.”

Brandon Kielbasa, director of organizing and policy at the Cooper Square Committee — a nonprofit focused on affordable-housing preservation and development in the East Village and Lower East Side — said some of the most aggressive landlords they see are the ones doing a lot of reckless construction, which often leads to lead contamination in the buildings.

“They are trying to make these affordable units into luxury apartments and they want to do it as fast as possible,” he said. “The tenants who stay on have to fight and are exposed to toxic lead and other elements. They are viewed as an obstacle for making a profit and not a human being living in a building that’s a dangerous construction zone.”

Matthew Chachere, an attorney for Northern Manhattan Improvement Corporation, who has been working on lead-paint litigation for the past quarter-century, said the issue is not the laws but their lack of enforcement.

According to Chachere, the law states that if an apartment becomes vacant, the owner has to permanently abate lead paint on high-risk surfaces. Additionally, for apartments housing children under the age of 6, landlords must inspect the apartment at least once a year for lead-based paint hazards. They must document the findings, with an E.P.A.-licensed-firm certification in writing and give it to the tenants, who can then hold onto it for 10 years.

While the Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Act, or Local Law 1 of 2004, states landlords found guilty would be charged with a misdemeanor and either a fine of $500 or six months in prison, Chachere said there isn’t enough enforcement.

“Why obey the law if no one will come after you?” he asked.

He also criticized the press’s coverage of lead poisoning, saying that often public housing is the focus of news coverage, when in fact it’s pre-1960 homes, like many of the ones in the East Village, that are the most dangerous.

A 2016 D.O.H. report found 4,928 children under the age of 6 with blood lead levels of 5 mcg/dL (the national reference level) or higher throughout the city. Additionally, 82 percent of children with blood-lead levels of 15 mcg/dL or higher were black, Latino or Asian, the report found.

“Children are not miniature adults,” Chachere said. “Their metabolisms are different. Their brains are at a different developmental stage. Their behaviors are different.”

He added that often little kids use their hands and mouth to make sense of the world around them. In their early years, they spend a lot of their time on the ground, crawling around.

“The part that gets under my skin is that when you have someone who is injured because of lead, the damage is often irrevocable,” Kielbasa said. “The damage is permanently done.”

Lead poisoning in the bloodstream can damage red blood cells and cause anemia. Lead that ends up in the bones can interfere with the absorption of calcium, which bones needs to grow strong. There can also be other long-term effects, such as damage to the nervous system, speech and language problems, developmental delays and even seizures.

Kielbasa also said that the contractors who are often day laborers are also acutely exposed to this lead.

On the other hand, he said, “The person at the top — the landlord, the developer and the bank — they are all completely insulated and away from that.”

Beyond the lead issue and the psychological stress this has added, Slayton has been dealing with mice running around the building, contractors working all hours of the night making noise and banging on doors, and workers welding without permits. On top of all that, she and her daughter have had to live for weeks without heat or hot water.

“When the contractors were there, they were partying and screaming, staying after hours, stealing packages,” she said. “They don’t even notify us when they are coming in and doing work so we can protect ourselves. You can’t even be relaxed in your own home.”

SaMi Chester, housing organizer at the Cooper Square Committee, said Madison Realty Capital has been taking its time addressing Slayton and other tenants’ concerns.

“They are trying to get rent-stabilized people out of the building,” he said. “They are really using everything they can in their playbook to empty that building. A lot of their responses are very apathetic: a lot of phone calls and e-mails that make no sense. It’s another harassment tactic to drive people into apathy.”

The only solution Kielbasa, Chachere and Chester could offer was there’s power in numbers. Joining forces with the remaining tenants, forming an association and pushing back collectively are the best forms of protection.

“Call 311 and complain,” Chachere said. “Tell them you are concerned and that you have a young child in the dwelling. Tell them the owner is doing construction and you are worried about lead. Call your councilmember, state senator and mayor. There’s a mechanism in place for this but unless people complain about it, it’s not going to happen.”

Phone calls and e-mails to Madison Capital Realty requesting comment were not returned by press time.