By Albert Amateau

Jane Jacobs, whose ideas about how cities prosper shattered urban planning principles 40 years ago, returned to the Village last week to speak at a benefit for West Village Houses, the low-rise affordable housing complex she helped to create.

A resident since 1968 of Toronto, where she went with her family to prevent her two sons from being drafted, Jacobs spoke to about 300 West Village residents on Fri., May 7, recalling the successful struggle against the late Robert Moses, whose urban renewal plans included demolishing a swath across Manhattan at Broome St. for a cross-Manhattan expressway.

“I feel like I’m in a time machine,” she told cheering West Village residents. “We always thought of the people who would live here when our vision for the West Village Houses was realized and we believed they would be the guardians of our plans. And here you are.”

West Village Houses tenants, who dominated the Friday event, are working to acquire the 42-building complex from current owners and hope to establish a limited-equity co-op that would allow the 420 families in West Village Houses to remain in their apartments at reasonable rents after the complex leaves the Mitchell-Lama program.

The day before, Jacobs, 88, addressed more than 1,000 people for two hours as the speaker at the Louis Mumford Memorial lecture at City College, on the subject of the development of cities from ancient times to the skyscraper era.

Since her groundbreaking “Death and Life of Great American Cities,” which has never gone out of print since it came out in 1961, Jacobs has published several books on city life including her latest, “Dark Age Ahead,” just issued by Random House.

In her new book, Jacobs argues that unless we reverse the decay of community and family, higher education, science and technology, representative government and the self-regulation of the learned professions, we are headed for a dark age of our own. She cited Japan and Ireland as two successful examples of cultures that are preserving their special characters while accommodating change. Her visit to New York City was part of her tour to promote her new book.

At the Friday event, she recalled her first days in New York in 1934. Just out of high school in Scranton, Pa., Jane Butzner was living with her sister in Brooklyn when she discovered the Village, the neighborhood that inspired her observations about city life.

After a morning of answering employment ads in Depression-era Midtown, she would get on a subway and get off at various stations “where I had no idea where I was,” and walk around exploring, she said.

“One day I came out at a place called Christopher St,” Jacobs recalled. “I went home and told my sister that we ought to live around Christopher St. — what appealed to me was the scale of things, the craftsmen’s shops, places that interested me.”

That method of exploration also launched her career as a freelance writer. She noticed that businesses tended to cluster, and found herself one day in the fur district. “A man came out of a store and told me his name was Edgar Lehman and gave me the history of the fur district,” she remembered. “I wrote an article about it — it wasn’t very hard — practically word for word from Mr. Lehman. I took it to Vogue and they paid me $40. It was a lot of money — when I did get a regular job, they paid me $12 a week.”

She subsequently wrote articles about the leather district (long gone from Manhattan), the flower district and the diamond district, which was then around Canal St. on the Lower East Side.

Her observations and conclusions about the interactions of people, where they work and live in urban settings, were sharpened after she married Robert Hyde Jacobs, an architect, and began writing for Architectural Forum. An assignment to interview Edward Bacon, a renowned city planner in Philadelphia, was a turning point.

“He was a quite a big pooh-bah. On a tour of the city, he took me along a street that was crowded with people — it was just after the war [World War II] — migrants from the South. People were looking out of their windows, kids playing in the street, people sitting on the stoops,” she said.

“He [Bacon] had a long face. He then took me one street over — there wasn’t a solitary soul in sight, except for a little boy kicking a tire in the street. I asked him ‘Where are all the people?’ But he talked about the marvelous vista. I wanted to know why people weren’t admiring the vista, and he said, ‘They don’t appreciate these things.’ He wasn’t interested in people. It was quite a revelation,” Jacobs said. “I didn’t have any credence in him any more. So I made myself my own expert.”

Many urban planners and architects rejected her conclusions about the necessity for a threshold of urban density and the importance of mixing uses. “They had everything invested in what they believed, and I had nothing to loose,” Jacobs said. “But it was clear that urban renewal was official vandalism based on anti-urban assumptions.”

The battle against a 14-block urban renewal project in the West Village was based on the assumption that the neighborhood would be designated a slum. “It always began with a study to see if a neighborhood is a slum,” Jacobs said. “Then they could bulldoze it and it would fall into the hands of developers who could make a lot of money.”

Jacobs said her husband had pointed out that the amount of money devoted to the cost of a study was directly related to the cost of the ultimate project: “They were going to add so many more units of housing than already existed, but we noticed it was very expensive per unit. They said they would preserve existing housing; it was their regular line — but they lied. We had informants who told us they had no intention of preserving anything.”

In Jacobs’ view, David Rockefeller was the main adversary in the urban renewal project, while Moses — “There was a great dictatorship under Robert Moses” — was the foe in the Lower Manhattan Expressway project.

“We owed a lot to Lester Eisner, the federal housing official in charged of the Northeast,” noted Jacobs. “We took him on a tour of the neighborhood and he was floored by what a nice neighborhood it was and the great range of incomes. He told us to never ever tell anyone in state or city government what you want for improvements because then you’re considered a ‘participating citizen.’ Then they can say they have citizen participation and do whatever they want. He told us not to be afraid of being considered ‘merely negative.’ ”

Mayor Robert Wagner Jr. finally lifted the slum designation from the South Village. “James Felt, the head of City Planning, had a fit — he turned purple,” Jacobs said. The West Village Committee hired Chicago architects to design the West Village Houses because New York architects who dared to design the project would be blackballed from big projects, Jacobs said. “We had to make some accommodations for the economies of mass production, so we couldn’t make the buildings different from the other,” she said. “Elevators drive skyscrapers, not the other way around, and we wanted low-rise walkups with no elevators. Fortunately, there was a study out that said walking up stairs was good for the heart and we made good use of that,” Jacobs recalled.

Ray Matz, the architect from the Chicago firm for West Village Houses, was at the Friday event and recalled an elderly couple who testified in favor of walkups. “The woman said she was 75 and her husband was 77. ‘We walk up five flights every day,’ she said, and then pointed to her husband. ‘Look at him — and he’s great in bed,’ ” Matz said.

Jacobs insisted that no one person was the hero of those struggles. “I get much too much credit for this,” she said, “There were hundreds and hundreds of people — leaders of all kinds.”

The fight against the Lower Manhattan Expressway came later. “The hero there was the priest at Most Precious Blood Church in Little Italy. He saw that his congregation would be destroyed and he got us [West Village activists] interested in that battle. By this time we understood what implications these bad plans had for the rest of the city,” said Jacobs.

Jacobs, who uses a walker, was guided by Ned, one of her sons, who is currently writing a book about what it was like to grow up in a family engaged in the struggle to preserve the Village.

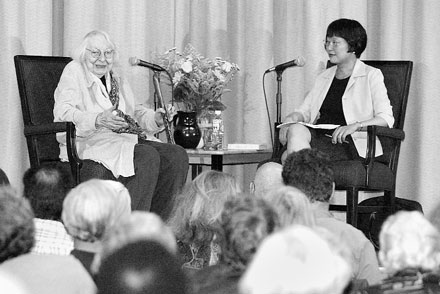

Katy Bordonaro, president of the West Village Houses Tenants Association, introduced Jacobs; and Mi Ling Tsui, a West Village Houses resident, served as interviewer.

“I’m very grateful to the West Village for being such a great community,” said Jacobs as the interview drew to a close.

Read More: https://www.amny.com/news/juniors-division-bucs-top-sox-12-1/