By Ed Gold

The last supper. There was wine and there was bread.

But there was also lots of veal, filet of sole, wild salmon, spaghetti and meatballs, and chef Bruno Mazza’s final round of Friday specials, ossu buco and duck. And martinis, lots of martinis.

It was closing night at Beatrice Inn, the West Village eatery, steeped in history, which was ending a 50-year run, and closing its doors on anxious regulars who would be looking for a new home away from home that would be cozy, exhilarating and not very expensive.

Elsie and Ubaldo Cardia, who had married after a 10-day courtship, looked for a way to make a living and bought the restaurant on 12th Street near Hudson in 1955. Later, in the late ’60s, they wisely acquired the 12 apartments over Beatrice.

The couple were later joined by son Aldo and daughter Vivian in running the business. Ubaldo died in the ’90s and Elsie passed way earlier this year, and their offspring sold the building and restaurant some months ago and decided to call it quits at the end of October.

This past Friday, they were both at their posts as the end approached, Vivian, ever glamorous, as hostess and cashier; Aldo, looking like an overworked waiter — although he was probably one of the richest people in the restaurant — rushing from one table to the next in the face of an overflow crowd.

A large number of regulars turned out for this last meal, some filling the small side room where many of the most conspicuous Beatrice loyalists would frequently gather.

In the “saleta” for the final evening were the Gabels in the far corner, the mild-mannered insurance executive Dan flanked by the more animated Bunny, a teacher and West Village activist. Daughter Elizabeth, now 25, was also on hand and Bunny explained that “we first brought her here when she was 1 month old.” Two other regulars, the Shermans, Arthur, the teacher, and Barbara, the artist, later joined them.

The adjacent table was chaired by Civil Court Judge Joan Kenney, whose 20-month-old daughter, Grace Elizabeth Mahon, sat beside her, closely watched by her daddy, Patrick Mahon, who said the baby had been a Beatrice Inn regular since she was 12 weeks old. “She’s become my big occupation,” he added, “although I occasionally work as an electrical engineer.”

Other regulars at the Kenney-Mahon table were Carol Feinman, a former Community Board 2 chairperson now an administrative judge, who became a steady at Beatrice after attending Waterfront Committee meetings in the West Village; and Paula Feddersen, who once operated a bookkeeping consulting firm.

In the other corner, one of the six-days-a-week patrons, Arthur Stoliar, worried about where he would relocate for dinners. Stoliar, also a former chairperson of C.B. 2, a former engineer and a fly fisherman of note, was joined by Civil Court Judge Diane Lebedeff, who used to frequent Beatrice often when she lived around the corner 25 years ago, and this writer. Joining the Stoliar table later was Judy Maxwell, the jazz enthusiast.

The table near the door was occupied by another six-dayer, John Simon, self-proclaimed “atheist and red,” who has been a publisher, WBAI station manager and talk show producer on Channel 13. He held open a seat for his steady companion, Kathy Dubkin, who was tied up on her Channel 13 job and couldn’t make the closing.

Simon, like some of the others, is still looking for a suitable food haven, but he tried to rise above his anxieties. He was sorry, he mused, that “we’ll miss several days of good conversation about Gordon Liddy,” referring to Lewis “Scooter” Libby, Vice President Dick Cheney’s chief of staff, who had just been indicted in the C.I.A. leak case. He added he would miss seeing Grace Elizabeth, the Mahon-Kenney daughter, who had become something of a star at Beatrice.

While there was mostly light talk in the small room, with Kenney demonstrating a gift for ribald humor, one topic turned everyone sober when someone raised the issue of Hillary Clinton and the presidency, followed by a wild assortment of conflicting opinions.

In the main dining room, unlikely tablemates who were Friday regulars were having their usual enthusiastic get-together. Gloria Triano, who reveled in having been secretary to the famous Tammany leader Carmine DeSapio, clicked glasses with the influential artist Jack Levine.

A few notables couldn’t make it, including a Friday regular, George Arzt, former Mayor Ed Koch’s last press secretary, who recently steered Robert Morgenthau to a victory in the Democratic primary for Manhattan district attorney; also, Howell Raines, the former executive editor of The New York Times; Joel Pave, a longshoreman who usually sat in the side room where he bemoaned the low status of unionism in America; Gwenn Gorovin, the physician with special interest in nose and throat, who has treated such singers as Placido Domingo and other greats; and Andy Ward, owner of the P.E. Guerin decorative hardware store in the Village.

Vivian Cardia remembers well some of the special groups that used to gather at Beatrice.

Both the Italian Rountable and the Algonquin Roundtable held meetings at Beatrice, and printers from such companies as Superior Ink and John Swift & Co. would fill the place for lunch, make lots of noise, eat and drink heartily and at times engage in games of chance.

But there were also gatherings held by the Kiwanis Club and the Accordion Association and serious labor discussions by the Union of Operating Engineers.

Celebrities came as well. Charles Kuralt of CBS was a regular, and Jane Jacobs, the urbanist, was also seen frequently. Entertainers like Larry Adler, Larry Hagman and Lloyd Bridges ate there, and Paul Draper “would get out of his chair and dance on the tables,” Vivian recalled.

Two incidents stand out in her mind. “Mayor John Lindsay scheduled an inaugural dinner at Beatrice in the late ’60s and then couldn’t show up because he was tied up with a city subway strike.” And “Helen Gurley Brown of Cosmo came to lunch one day and said she was disappointed. She thought she was coming to a fancy joint.”

As the hours advanced on this last night, Beatrice began registering stock shortages. Aldo noted that they had run out of stuffed clams, then breadsticks and also fruit salad.

But he discovered a partially filled bottle of grappa, a wine made from grape discards, and offered it as a parting gift to side room regulars, who gratefully accepted it.

In a touching scene late in the evening, two fairly regular patrons showed up and tried unsuccessfully to squeeze into the saleta. But Wendy Doremus, who lost her husband on 9/11, and friend Christine Edonomos, who works at the Museum of Natural History, although very disappointed, showed good spirit, wishing everyone the best with hopes that they would all meet again.

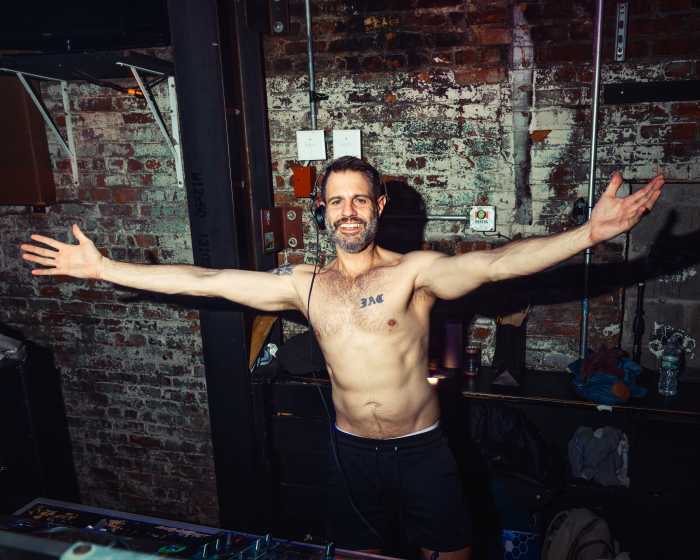

Possibly the most impressive ambassador of goodwill was Bruce “Cousin Brucie” Morrow, disc jockey and radio personality, a large, hearty man who shook hands at each table and said the Beatrice crowd had been “part of my family.”

Saddened by the closing, he asked all around: “Where will you refugees go?” But he was sympathetic with the Cardias. “Aldo,” he said, “just wants his own life.”

Aldo, in fact, isn’t sure what he wants to do. He is a Scrabble player at the national tournament level and will likely be seen at Scrabble tables in Washington Square Park, but he’s not ready to call that a meaningful career.

As for Vivian, she is taking on a new responsibility, and is in the process of adopting her 5-year-old grandson, Nicholas, whose mother — Vivian’s daughter — died last year.

Taking a short breather, Aldo mentioned the open house that was scheduled for Saturday, adding: “I think we’ll have mostly leftovers. It’s been so busy tonight”

Drenched but smiling, he took some satisfaction in the fact that Beatrice Inn was S.R.O. for the last supper.