Noise from the Manhattan West project ended home recording work for musician Even Steven Levee.

BY ZACH WILLIAMS | For those who’ve put down roots in West Chelsea, the impact of ongoing residential development is hitting home — early in the morning or late into the night, often at the expense of restful sleep and normal everyday activities.

The New York City Department of Buildings (DOB) allows construction to take place outside of the generally allowed time frame — 7 a.m. to 6 p.m., Monday through Friday — by issuing an After Hours Variance (AHV). To obtain that permit, applicants must successfully cite emergency conditions or demonstrate a threat to public safety, such as traffic congestion or worker/pedestrian danger during normal hours. City construction projects in the public interest, evidencing undue hardship (such as unforeseen conditions and scheduling commitments), and limiting work to that which creates “minimal noise impact” are also acceptable reasons for obtaining an AHV. Once granted, it’s valid for up to14 consecutive days, and renewable online through the NYC Development Hub.

Residents living within earshot of an AHV site say that even the most robust noise mitigation plan — a requirement for all construction projects regardless of the hours they keep — still exacts a toll on peace of mind and quality of life.

Three noise complaints made to 311 regarding after hours construction at have been to no avail, according to Cynthia Butos. The backyard of the W. 15th St. building in which she lives with her husband Bill faces a 245 W. 14th St. project, where workers were hammering and sawing on a recent Saturday morning. The noise was so intrusive, they decided to forego the annual spring planting of their basil crop — which, in prior years, supplied a weekly pesto dinner to building residents. Relaxing in the backyard has been impossible due to the ongoing construction work, she noted in an email.

“The weekend work affects more than just the eight apartments with garden access, though. About 30 apartments face the construction, so when they are home on Saturdays, they are awoken and live with the noise,” said Butos.

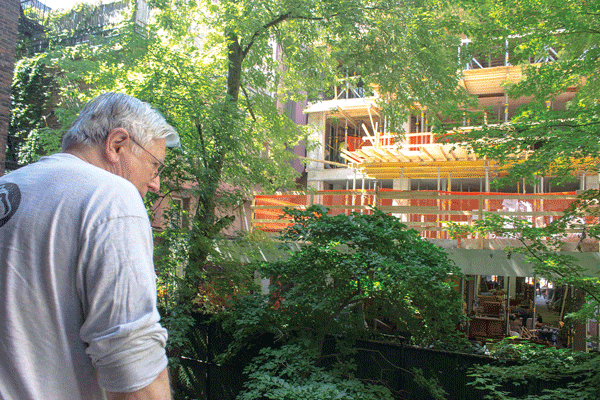

Pestered to the point of no pesto: W. 15th St. resident Bill Butos observes the garden impacted by early morning construction on a 12-story resident building adjacent to his backyard.

Decades-long neighborhood advocate Stanley Bulbach, currently president of the W. 15th St. 100 and 200 Block Association, asserts that the “tsunami of poorly designed and regulated hyperdevelopment” has residential communities throughout West Chelsea “increasingly overwhelmed.” The present atmosphere, notes Bulbach, was created and nurtured during the three terms of mayor Michael Bloomberg — who, said Bulbach in an email, neglected “regulations and guidelines protecting residents, but complicating hyperdevelopment.” One such example: the future 12-story residential building at 245 W. 14th St., whose AHV disruptions prompted Butos to make her 311 calls. When construction commenced several years ago, it produced tremors, recalls Bulbach, who noted that inspectors halted work for “a couple of years.”

Construction noise as late as 4 a.m. and as early as 7:30 a.m. has taken its toll elsewhere, according to Jeff Sokolowski, who lives with his wife and daughter on W. 34th St. — near the sprawling Manhattan West project. Heavy machinery, truck engines, and other disturbances impact their sleep and dissuade them from enjoying the balcony (an amenity which, in part, motivated them to move to this location).

“There’s been drilling. There’s been jack hammering. There’s been pile driving,” Sokolowski said before adding, “I know it’s kind of a bourgeois complaint, but that’s [the balcony] one of the benefits of our apartment.”

Another resident of W. 34th St., Even Steven Levee, said the Manhattan West project has put the damper on his home recording studio, among other inconveniences.

“It’s been insane to say the least,” he said.

Brookfield representative Melissa Coley declined to answer questions concerning the reasons that the project secured an AHV for Manhattan West, but expressed optimism that conflicts stemming from the project would ultimately be resolved, she said in an email.

“Since before our Manhattan West project began, we engaged in a cooperative dialogue with the various stakeholders in the community to communicate all facets in our construction program and provide a method to address issues as they arise,” she said in the email. “We will continue to be actively engaged in that dialogue and look forward to completing the project that will include two acres of open space and multiple public amenities that will enhance the neighborhood for everyone.”

According to a website devoted to the $4.5 million project, Manhattan West will feature a 60-story residential building with 800 luxury units as well as a five star hotel, retail space and a two-acre park. Construction on a three-acre foundation for the site began in January 2013, Chelsea Now reported on Feb. 26.

Representatives of two prominent real estate development companies, Extell Development and Related Companies, did not respond to multiple requests for comment on the necessity of AHVs for their projects throughout New York City, or their reaction to the proposed legislation. Related Companies is currently developing Hudson Yards, property bought last year from Extell for $168 million.

According to DOB records, developers within the boundaries of Community Board 4 (CB4) were issued 2,442 AHVs in 2013 — with 1,206 so far this year.

“These are literally on a case-by-case basis so [developers] have really got to present a specific reason why they need to operate outside regular construction time,” DOB spokesperson Alex Schnell said.

The department conducts spot checks of active AHV sites, and follows up with complaints made via 311 in order to ensure compliance, noted Schnell. But the number of permits, which are actually revoked based on complaints and inspections, “are pretty negligible,” Schnell noted.

DOB records show that such action was taken 22 times in 2013 and twice this year, within CB4. Citywide, the numbers are 246 in 2013 and 39 in 2014. Proposed legislation before the City Council seeks to curtail the issuance of the permits, though no date has been set yet for discussion by the council’s Committee on Housing and Buildings.

Changes to the city administration code would limit AHVs to between 7 a.m. and 8 p.m., Monday through Friday, and 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. on Saturdays. If the proposed legislation passed, AHVs could not be issued for Sundays. Developers would also have to post the hours of construction under the variance at the site itself. The DOB and the developer would have to publicly release a written decision explaining a rationale both in approving and applying for an AHV, respectively. Email notifications would alert residents of variances approved for sites within their community board districts, according to the bill proposed by Rosie Mendez, whose district includes the Lower East Side.

Comment on the legislation, including when the bill would be scheduled for a committee hearing, from her office was not available by press time despite multiple requests for comment made via telephone and email. The DOB has no position on the proposed legislation at present, Schnell said.

The proposed legislation follows discussion last year on the impact of AHVs on the quality of life in CB4. “The current process is very one-sided,” said CB4 chair Christine Berthet in an email to Chelsea Now. “It only takes into account the needs of construction companies and disregards residents’ needs.” Redevelopment and “massive rezoning,” she noted, exasperate ongoing noise issues in an area that’s already replete with rowdy bar crowds and traffic.

Chelsea’s District 3 representative, City Councilmember Corey Johnson, one of 11 co-sponsors, says the bill is about “having some accountability for how the DOB is allowed to grant these [AHVs]. We hear from constituents all the time about it.”

The involvement of council members throughout Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, and The Bronx in furthering the bill underscores the scope of the problem as well as the potential for a political solution in upcoming months, said Johnson. Another co-sponsor, Councilmember Margaret Chin, asserted that ultimate passage would ensure that “common sense measures” are in place to protect vulnerable constituents such as children and the elderly.

“We must remember that the impact of development projects isn’t just a future impact, in terms of creating new homes or offices,” Chin said in a statement. “These projects can also have seriously negative effects on the neighboring residents who have to live through the construction work.”