BY DUSICA SUE MALESEVIC | For the Coalition for the Homeless, a major piece of the puzzle to get people off Manhattan’s streets for good is providing permanent housing rather than looking to the city shelter system as a solution. Under the group’s approach, known as the “Housing First” model, a homeless individual or family gets long-term affordable housing, which, depending on need, sometimes comes with support services.

Giselle Routhier, policy director for the Coalition for the Homeless, spoke about the necessity of supportive housing at the November 17 meeting of the Midtown South Community Council (MSCC), a group that was already focused on the homelessness issue.

“Supportive housing is crucial for homeless individuals who are living with severe mental illness or other disabilities, including physical [or] developmental,” Routhier told the crowd at the New Yorker Hotel on Eighth Avenue and 34th Street. “It’s really proven to be effective at getting people housed and keeping them housed.”

Housing is the first step in recovering from difficulties a person may be dealing with as a result of living on the street, Routhier explained. When a homeless individual has a stable place to live, he or she is best situated to tackle problems including substance abuse and mental illness, she said.

As the Coalition’s policy director, Routhier said, she oversees advocacy in New York City, the cardinal principle of which is a housing-based approach to homelessness. The group has pushed both the city and state for more supportive housing units. Mayor Bill de Blasio has committed to 15,000 units for the city, and Governor Andrew Cuomo made a pledge to create 20,000 units statewide.

Routhier said de Blasio has already made progress on his commitment, with several hundred units slated to come online this year. While the Legislature allocated funding in the most recent state budget for the first 6,000 units, that money has not yet been released, she explained.

“We’re in a really unfortunate gap period where the new units have not come online yet and… most of the old units are actually not funded anymore,” Routhier said, noting that there are six or seven applicants per each unit of supportive housing and “it’s a tough spot we’re in right now.”

In response to a question from Community Board 4 member Allen Oster, Routhier said the Coalition supports a move by the city that would require developers to set aside half of affordable housing units within a community for the homeless. CB4 opposes that plan.

After the meeting, Oster said, “I think CB4 has worked very hard to get affordable housing in our community.”

In her presentation, Routhier explained that the Coalition provides 11 direct service programs, including a mobile soup kitchen called the Grand Central Food Program. Three vans run routes throughout Manhattan and the Bronx, which give out hot meals at set stops, she said.

The Coalition was founded in the early 1980s as the result of a lawsuit involving a homeless man denied space in a city shelter because there were no more beds available, Routhier said. A founder of the group argued that according to the New York State Constitution, there should be a right to shelter, and that right was established for homeless single men at that time. The same right was eventually extended to homeless single women and homeless families with children, Routhier explained.

“New York City is very unique,” she said. “We’re the only municipality in the United States that has a right to shelter for families and single adults. That’s important to recognize and remember.”

According to a recent US Department of Housing and Urban Development report, which compared Los Angeles and New York City, 75 percent of the homeless in LA are unsheltered while that number is five percent here, she said.

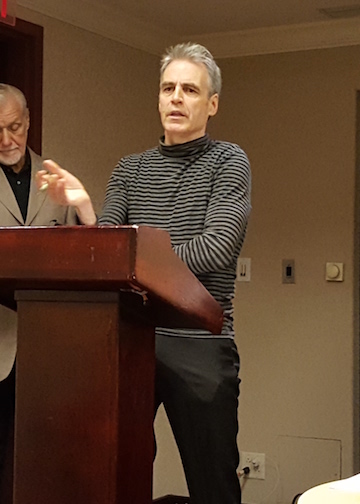

MSCC’s president, John A. Mudd, invited Routhier to speak at the meeting as part of his drive to build a consortium of city agencies and nonprofit organizations to help the homeless.

“When it comes to homeless, our philosophy is to do outreach, outreach, outreach,” he said.

Mudd recently spent time with people who were part of a homeless encampment on the street where he lives — West 38th between Eighth and Ninth Avenues — asking them why they were living on the street rather than in the shelter system. Partnering with the nonprofit Urban Pathways, he worked to clean up the encampment, which he said was starting to attract prostitution and drugs.

“We gave them a lot of warning that we were coming to clean it up,” he said. “We gave them a lot of access to a lot of different kinds of shelters.”

In a phone interview the day after the Coalition for the Homeless presentation, Mudd emphasized that they were very sensitive in how they broke up the encampment. The Friday before the removal, he spent about four hours talking to people there.

“We were well received by them because they know we want to help,” he said.

On October 24, a police officer, an Urban Pathways employee, and Mudd went to the encampment and threw out chairs, milk cartoons, and garbage, but left personal belongings alone.

He said there are other nearby encampments — on West 30th Street near Eighth Avenue, and on Eighth Avenue between West 33rd and 34th Streets — that he wants to clear by helping the homeless people who live there.

Midtown South Community Council’s boundaries run from the east side of Ninth Avenue to Lexington Avenue, between 29th and 45th Streets, but Mudd also helped with an encampment in Hudson Yards at West 35th St. at Dyer Avenue, between Ninth and 10th Avenues.

The encampment, which has since been broken up, had people staying there going back to the summer, said Robert Benfatto, executive director and president of the Hudson Yards/ Hell’s Kitchen Alliance, a business improvement district, in a November 21 email.

According to Benfatto there are no other homeless encampments in the Alliance’s coverage area, which spans the blocks between Ninth and 11th Avenues, from West 42nd Street south to West 30th Street. Homelessness, he said, is a major concern for the Alliance, but not a major problem.

For his part, Mudd said he is enthused with the progress he is making.

“Everyone wants to resolve the problem,” he said. “The more we continue in this direction, it’s the right direction.”