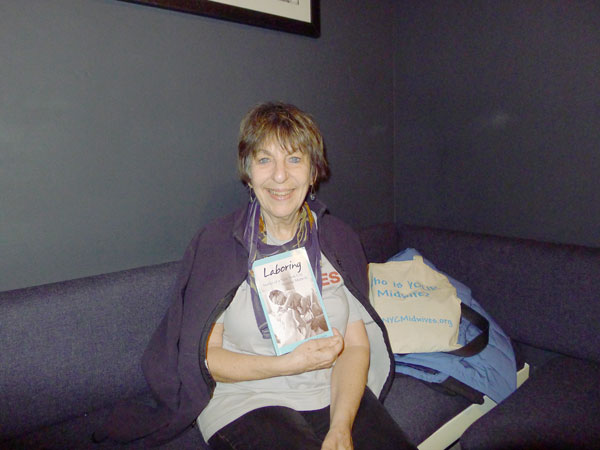

Ellen Cohen reads from her memoir on March 3, at Bluestockings (172 Allen St.).

BY HEATHER DUBIN | Ellen Cohen refused to play up the achievement of helping to bring over 1,400 babies into the world — but with a little encouragement, she did manage to deliver a memoir.

“It’s not a big number for an urban midwife really,” said Cohen of her career total, “but it’s good enough.”

In “Laboring: Stories of a New York City Hospital Midwife,” she details the steps she took to become a midwife. For over two decades, the longtime Penn South resident returned home from her workday to share stories with her husband and sister — who both told her, “Oh, you have to write this, Ellen.”

In a recent interview at Pushcart Coffee (West 25th Street, at Ninth Avenue), Cohen recalled various events leading to the writing of her memoir — noting that she was also encouraged by articles and books, which featured experiences and situations similar to her own. Inspiration was also provided by her former patients in New York City hospitals, who were primarily immigrants and on Medicaid. According to Cohen, 40 percent of hospital births are paid for by Medicaid.

“I didn’t write before, but once I made up my mind to do it, the writing was fun,” Cohen said. The book took a year and a half to complete, and she self-published it last December.

Cohen previously worked as a computer programmer for nine years, and prior to that she raised a family. The birth of her two children, both born in the 60s, and the women’s movement, served as catalysts for her entry to midwifery.

Cohen explained in the 60s, childbirth education was “just barely starting in this country,” and most women were knocked out, tied down and medicated. Also, they were not allowed to see their new babies until hours later.

Cohen’s friend gave her a childbirth book to read, which helped to better prepare her, and she refused anesthesia. “I had a very supportive nurse, I was very lucky. And when they put a mask over my face, the nurse said, ‘No, she doesn’t need it,’” Cohen said, “That was a very empowering experience. In those days, you didn’t question the doctor about anything. It was unheard of.”

Women were also instructed to gain no more than 15 pounds or maintain a salt free diet, neither of which were based on scientific studies, and are long gone practices.

Cohen wanted other women to have control over their own bodies during childbirth, and began her midwifery path, which landed her at Bellevue, Lincoln Hospital, St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital, New York Presbyterian, Allen Pavilion and The Center for Mother and Baby Care, an HIV clinic.

“95 percent of midwife births occur at hospitals, homebirths are all the publicity,” Cohen said. At the hospitals where she worked, midwives were not supervised by doctors, but if there was a problem, they consulted with them, and if necessary, turned the patients over to them. “In my whole career, only one person said to me, “I want to see a doctor,’” she said.

“Midwifery has been shown to improve birth outcomes, but it’s kind of a sad commentary on obstetrics in the United States that something like that is needed, and isn’t an integral part of the care,” Cohen said.

Women who use a midwife have outcomes as safe as under a doctor, and will be subject to fewer interventions, such as a cesarean section. Cohen pointed out that 80 percent of women are healthy, and have the baby in the right position, which contradicts a rising cesarean section rate, which has only plateued in the past two years.

“Many women feel coerced to have cesarean sections and other interventions, rather than other way around,” she said. Cohen also claimed maternal mortality rates are increasing in the states, in tandem with the soaring number of cesarean sections.

Cohen worked with pregnant teenagers in the 80s at her first job at Lincoln Hospital. “Each of the girls had their own midwife throughout the pregnancy. Most places where I worked, it was the same, in terms of individualized care,” she said. Cohen’s patients came from all over the world and were different ages and religions.

“Some are very interesting stories, most are happy, but some of them are very tragic,” she said. Cohen opens the book with a favorite story of hers about a mentally ill patient who gave birth on the floor of the hallway in a hospital. The attending resident, who was also seven months pregnant, did not know how to handle the case, and Cohen ended up taking charge to deliver a healthy baby.

Cohen also was involved in a research study preventing mother-to-baby HIV transmission at a clinic, where she worked for two and a half years. The findings were groundbreaking in the early 90s, and proved that AZT, a drug used to delay the development of AIDS, effectively prevented HIV infection. The standard practice to combat the virus then became AZT, which led to more advanced “drug cocktails” in later years.

Cohen, who retired in 2005, admits to missing being a midwife. “I felt I was providing a very important service to women who wouldn’t have had that kind of care. It was very gratifying,” she said.

However, she is content with her current role, and is very involved in midwifery activism. Cohen speaks at high schools on career days and at health fairs to promote the profession. She also works with the Manhattan chapter of the American College of Nurse-Midwives.

Cohen’s book is part of the curriculum for a midwife course at Columbia University, and a medical anthropology course at Hunter College. She is making a concerted effort to reach beyond the typical midwife readership, but Cohen certainly appreciates her cohort’s feedback. “I’ve been so pleased with what midwives have said: ‘This is my story, I’m so glad you did this,’” she said.

— At 7pm on Monday, March 3, Ellen Cohen will be reading from “Laboring: Stories of a New York City Hospital Midwife” at Bluestockings (172 Allen St., btw. Stanton & Rivington Sts.). A Q&A session follows the reading. More information can be found on the book’s Facebook page: tinyurl.com/pmhkfky.