A time capsule of an artistic, more affordable Soho

BY GARY SHAPIRO | For a Minimalist artist, Donald Judd’s presence in Soho is far from minimal.

Many in the art world know that Judd’s former home and studio at 101 Spring St. is about to reopen in June. But few know that Judd’s footprint in Soho is more expansive than this.

Well, it at least extends a little beyond Spring St. As befits a major artist, there is a kind of small corridor in Soho devoted to Judd.

How so?

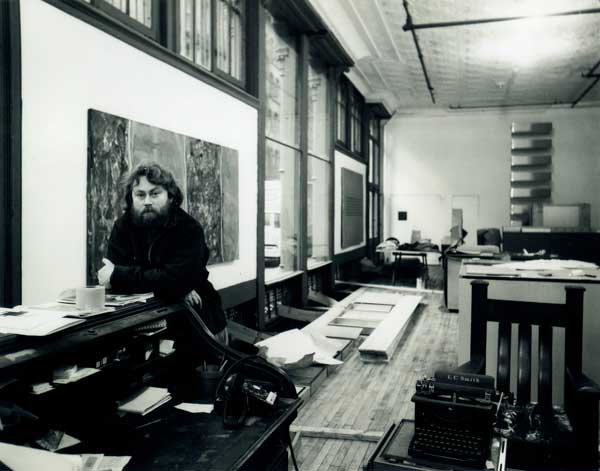

One of the main conservators and fabricators of Judd’s work, Peter Ballantine, resides three blocks away on Greene St. in a redbrick Federal-style building.

“I used to say my place is so close to Judd, you could walk there in the rain without an umbrella,” said Ballantine.

Ballantine bought his building on Greene St. in 1973, while Judd had purchased his building five years prior.

Judd had lived in a rental apartment on E. 19th St. but wanted more space. He laid out $65,000 for a five-story building on the northeast corner of Spring and Mercer Sts. in 1968. He purchased it on the strength of the success of a Whitney Museum retrospective of his work that year.

He was drawn to the building because of its scale and natural light, Julie Finch, Judd’s former wife, told The Villager.

The Judd Foundation, which was founded in 1996 by Judd’s last will and testament, will have its offices in the basement and subbasement of 101 Spring St. The first floor will have uses such as a temporary exhibition space.

The second floor is the kitchen, where meals were enjoyed with artists such as Carl Andre, John Chamberlain, Larry Bell, Dan Flavin and Robert Irwin, and musicians such as Philip Glass.

“We were always wining and dining our friends,” said Finch.

The third floor was Judd’s studio, which had originally been on the ground floor, which he moved for reasons that included wanting more privacy. The fourth floor at 101 Spring St. was a very seldom-used dining room with a pine floor and ceiling that run like parallel planes. The fifth-floor loft space was for bedroom areas.

“Don spent a lot of time thinking about where everything should go and what it should look like,” said the artist’s son, Flavin Judd.

Back in the late 1960s, Soho lacked certain amenities.

“I had to go all the way to Eighth St. to buy fresh dill and blueberry muffins,” said Finch. She recalled making these trips while pregnant with their daughter, Rainer, and pushing along Flavin in a stroller.

Rainer Judd is now a filmmaker, who has completed a short film called “Remember Back, Remember When” about her parent’s divorce as seen from the point of view of the two children.

A meticulously restored cast-iron facade at 101 Spring St. was revealed when decade-long scaffolding came down this year. The project architect on the renovation is the firm Architecture Research Office. Under ARO’s leadership, Walter B. Melvin Architects has overseen the exterior restoration and Robert Silman & Associates has been the structural engineers.

A key fabricator for Judd, Ballantine began by doing carpentry for the artist on his Spring St. building beginning in April 1969. Ballantine had originally met him in February 1968 while studying at the Whitney Museum’s Independent Studies Program. Judd had come to give a seminar, as had others like Frank Stella, Barnett Newman and Roy Lichtenstein.

Even though Judd lived three blocks away from Ballantine, interestingly, Judd only once visited the site of his important art fabricator on Greene St. This was in 1973, the year Ballantine bought the place. Judd’s visit, Ballantine said, was only prompted by the artist’s like of old buildings.

In a New York Times article, architectural historian Christopher Gray cited research showing that Ballantine’s building on Greene St. was once a brothel in the 19th century, ensconced in a red light district. Art dealer Richard Feigen had used the building for storage for his gallery one building north.

Judd’s son Flavin said of Ballantine’s unadorned Greene St. building, set amid neighborhood commercialization: “His little house is looking good — it’s a nice antidote to shoe shops and hip fashion stores.”

From 1969 to 1994, Ballantine went on to fabricate about 250 works of the artist. Ballantine has since hosted conferences and symposia relating to Judd: One title had a Latin phrase whose humorous translation goes to the heart of what art fabrication is about: “Judd made it, but he didn’t make it.”

In the decade after Judd’s death, Ballantine has worked to preserve and restore a large number of the artist’s works. He was art supervisor of the Judd Estate from 1994 to 2000, and subsequently of the Judd Foundation till 2004.

Presently a freelance curator, restorer and consultant, Ballantine is currently working on Judd symposia to take place in New York and Berlin next year. They will address Judd’s process of delegating the fabrication of his works. As part of the New York event, Ballantine also plans to exhibit a Judd drawing show he had previously curated in London and Edinburgh.

Judd is difficult to pin down: He used terms like “specific object” or “three-dimensional work” rather than “sculpture” or “artwork.”

“Judd did not consider himself a Minimalist, but of course everyone calls him one,” said David Raskin, chairperson of the department of art history, theory and criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. “It’s common for critics to coin names and for artists to reject them,” he added.

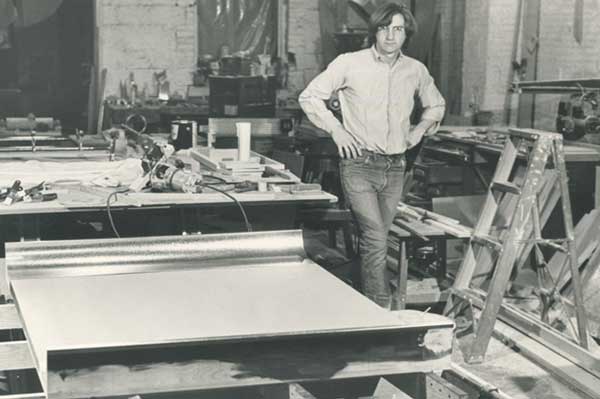

Box-shaped sculptures became Judd’s signature form, making him one of the pre-eminent figures in the 1960s and ’70s. His spare, nonfigurative art drew attention in the wake of Abstract Expressionism.

“Judd asked himself whether a new sculptural form was possible,” said Richard Shiff, an art history professor at the University of Texas at Austin. “His solution was to allow his sculptural forms to project abruptly from the wall or rise abruptly from the floor. This is why the boxlike forms held such attraction for him. They had a quality of abruptness that ensured that they did not reduce to a set of pictorial transitions in space.”

Judd’s early pieces from the beginning of 1964 were made in a sheet-metal factory called Bernstein Brothers, and later on made by others. They were in part the result of Judd’s looking to such professional expert sheet-metal workers to do a superior job in making beautiful pieces.

As Raskin of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago said, such delegation was also a deliberate attempt to prevent the handwork of the artist from having expression.

Raskin noted that after Judd hit upon the three-dimensional rectangular pieces, he explored these closed and open forms in a variety of materials, such as metal, plywood, cement and Plexiglas, sometimes having internal dividers that are perpendicular, diagonal or parallel.

“He is taking a basic shape and exploring all these permutations,” said Raskin.

Shiff of the University of Texas Austin said, “You have to view Judd’s forms from all angles in order to appreciate them, even though you may think that you know what a ‘box’ is. He had many ways of complicating the sensation of the form with surface reflectivity, color contrast, changes of scale and the like.

“At any rate, let me say that if you live with a Judd object, it’s like no other object that you know,” said Shiff.

Judd, who was born in Missouri, studied philosophy at Columbia University, and went on to study at the Art Students League. He pursued a master’s degree in art history at Columbia University, where he studied with Rudolf Wittkower and Meyer Schapiro. He completed the prerequisites for his Master of Arts, except for the language requirement. Ballantine believes Judd’s study of philosophy at Columbia, particular the British empiricists, had a greater impact on Judd than did his study of art history.

Fitting for the son of a Western Union executive, Judd traveled. After spending time in locales like Baja, Judd moved to Marfa, Texas, in 1977. Adam Yarinsky of the project architectural firm ARO said, “101 Spring St. is where Judd conceived his idea of the permanently installed space, which he subsequently developed on a much larger scale in Marfa.”

Flavin Judd said, “Sparse, unpeopled Marfa was the perfect contrast to New York.” The faded area was famously featured in the movie “Giant,” featuring James Dean, Elizabeth Taylor and Rock Hudson. Trains had ceased stopping there in 1971.

“Real estate was cheaper than New York. He could buy a former Army base,” said Raskin. A former supermarket, a former bank and a former grocery store joined Judd’s collection of buildings. In fact, one of the next big tasks of the Judd Foundation will likely involve working on 16 buildings there.

Julie Finch said that Judd loved the desert because the plants had the same relationship to the flat land as Judd’s pieces did to the floor.

Judd’s theoretical writings have drawn the attention of critics, which is fitting since Judd himself wrote for art magazines early in his career.

Raskin said Judd wanted the viewer of his art to stave off as long as possible seeing his work as a metaphor for something else. He said those who would reduce Judd’s work to “making a dull presentation of material facts, such as, ‘Here is a piece of metal, and here is another piece of metal,’ don’t want to engage the sensual complexity of the visual experience.”

The next generations of artists will have an opportunity to learn from Judd by visiting 101 Spring St. beginning this June. The property will show what Soho once meant to artists before many of them were priced out of the neighborhood.

Art students can seek out Judd’s studio and home to inform their own work.

“Judd thought that each generation of artists ought to create forms unique enough to bear the stamp of that generation,” Shiff said. “So he wasn’t rejecting the quality of past accomplishment, but arguing that artists should not get credit for merely extending the accomplishments of the past.”