By JERRY TALLMER

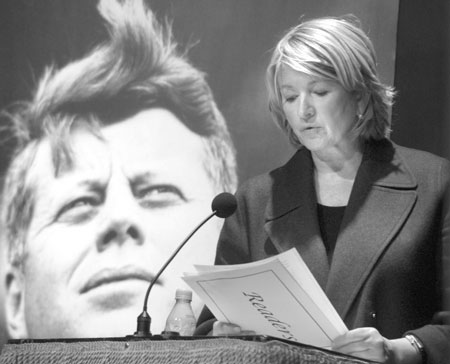

Marathon J.F.K. reading

Martha Stewart was one of the participants in a 24-hour reading last weekend of Jim Bishop’s “The Day Kennedy Was Shot” at Cooper Union’s Great Hall. The free marathon reading of the book, which gives an hour-by-hour account of J.F.K.’s assassination, was the idea of Bronx lawyer Dr. Howard Charles Yourow. Others reading for 20 minutes each included John Brademas, N.Y.U. president emeritus; Rep. Charles Rangel; Newsday columnist Dennis Duggan and Chrystine Lategano-Nicholas, president of NYC & Co. Cooper Union provided the Great Hall, but did not sponsor the reading.

The name doesn’t matter, and I have forgotten it anyway. He was a copyboy at the New York Post in the days when the New York Post was a newspaper and Dorothy Schiff was its owner (not to mention publisher, editor, everything). Let’s call him Morris. He was a Coke-bottle-lensed, overweight, froglike misfit of indeterminate age, maybe 28, a Columbia University graduate with a Ph.D. in something, and all the girls in the place — we still called them girls then — were terrified of him. I never exactly could find out why. Body odor was one reason. I’m not sure he actually had the guts to touch any of them, but maybe he did, accidentally on purpose.

In those years, news from outside the city, and often from inside the city, reached the New York Post city desk by way of an AP ticker, a vintage clickety-click device that spat out a constant ribbon of imprinted tape. When the dispatch carried urgent news, a bell on the machine let you know.

Copyboy Morris, that fall and winter, had the job of monitoring the AP ticker, which meant tearing off bits of tape at frequent intervals and conveying them to John Bott, the city editor, to Al Davis, the managing editor, and to Paul Sann, the executive editor, a Bronx cowboy (boots and all) who modeled himself after Walter Burns, the hard-boiled, caustic editor in “The Front Page,” a play and movie by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur.

Morris missed the first five bells, just after noon on Friday, November 22, 1963. Perhaps he was reading dirty magazines, or maybe some revolutionist like Regis Dubray. The city room of the Post in those days, on the fourth floor of 75 West St., was immediately adjacent to the composing room, where men at linotypes set the hot lead that cooled into lines of type that were then placed in forms and chases to make a page.

A printer came running and yelling from the composing room into the city room, a little portable radio clutched to his ear. “Kennedy’s been shot!” he yelled. “Kennedy’s been shot!” And that’s how The New York Post learned of the assassination of John F. Kennedy.

In those days, also, there were no computers, just battered old typewriters. You typed on “books” — three sheets of copy paper interleaved with carbons. One set of whatever you wrote went to John Bott, one to the copy desk, one to Sann. The copy kids would spend hours assembling “books.” In the hours that followed, that Friday, Dorothy Schiff came down from her penthouse atop 75 West St. and sat down and went to work putting together “books” at a desk in the city room.

The first morning I was ever at the Post, 18 months earlier, Al Davis, who had lured me to take employment there, said: “Sit down and watch. Here we have six orgasms a day” — meaning six editions — “and I was never more than a one-orgasm man.” Al believed in creative tension. He ran the city room that way, with sharp insight and manic discombobulation.

When the printer had run in with his hand to his ear, Al grabbed the guy’s radio and he and Sann and Bott were now all huddled around it, listening. I was at the far end of the city room when I heard just one word barked full volume with a touch of high hysteria by Davis: “DEAD!” For some reason, what flashed into my brain was the voice of Spike, the sadistic editor (Davis was nuts, but only peripherally sadistic) of Nathanael West’s masterpiece, “Miss Lonelyhearts.”

Not long later, Bott called me over and told me to go out and get man-on-the-street reactions. In the lobby of 75 West St. there was a little candy-and-newsstand run by a Brooklyn couple, a husband and wife in their 60s. Her name was Ada Greenfield. The first person I saw when I stepped out of the elevator was Ada Greenfield, and I didn’t have to ask whether she’d heard the news: It was written all over her anguished face. I said something stupid like: How do you feel about it, Ada? Forty years later I can still exactly hear her voice saying: “It’s like a great young tree cut down.” Forty years later, through all the millions and millions of words and thoughts and tears, no one has ever said it better.

I went out on the street. On the corner there was a stocky middle-aged man with a cigar, just standing there. He looked like a bookie or a small-time agent. I walked up and asked my dumb question. He just looked at me, or through me. He didn’t answer. He was crying.

I went into the bar that was our hangout. The bartender — George, I think his name was — just looked at me, with force. I didn’t ask my question. I went out, decided I wouldn’t ask any more people anything, went back up to the city room and wrote the whole story just quoting Ada Greenfield, It wasn’t a long story and didn’t have to be.

Whatever else I did in the ensuing hours at the paper I don’t remember — probably a ton of rewrite. When I finally did leave 75 West St. there was one place I wanted to go: to my alma mater, The Village Voice, then on the corner of Sheridan Sq., where every Friday night all sorts of people had a habit of congregating and shooting the bull with Daniel Wolf, an editor who was much more than just an editor.

When I got to The Voice, feeling completely hollow, benumbed, I somehow had the urge to write something. I sat down and rattled off, in agony, on one of The Voice’s even older typewriters, a short, terse, coldly angry piece in which it is Miss Lonelyhearts who hears Spike bellowing: “Dead!” into the frenzied wastes of a large city room. Dan put the thing in the next issue of The Voice, though I don’t know if he or anyone else ever understood it.

While I was still writing it, Jean Shepherd, radio spokesman of the Night People and an integral part of the Village Voice of those years, arrived at Dan’s office. He was, like everyone else, very upset, but in Jean’s case, in a unique way. He was raging, raving, laughing, all three together. “Wouldn’t you know,” Jean kept saying, “wouldn’t you know it would be someone from Fair Play for Cuba!” In short, that not an arch-reactionary asshole but a radical of some sort had just shot and killed the (more or less) liberal post-Bay of Pigs president of the United States. Jean was thunderstruck by the irony of it.

In the days that immediately followed, the Post set me to monitoring television. It was thus that I was watching, and listening, when, at Arlington, the bugler — the Army’s best — cracked on the high note of taps. It summarized for me everything about the assassination of J.F.K., and still does. That and Ada Greenfield.

Two days later, on Sunday, I was driving my wife and kids and their left-wing Bronx grandparents through Central Park. Three years earlier I had slid two lines of agate within a theater review of mine in The Voice: “Final score, November 25: Tallmer 2, Kennedy 1” — twins Abby and Matthew Tallmer having been born the same day in 1960 as John F. Kennedy, Jr.

Now, Sunday, in the station wagon, the radio was suddenly blatting: “A man named Jack Ruby has just shot Lee Harvey Oswald to death in the basement of the Dallas police station . . . “ I reached down and snapped the radio off. I thought the 3-year-olds had heard enough about death that weekend, as well as seeing John-John saluting his father’s coffin. But I did turn to their grandfather and said to him in a low voice, out of sheer intuitive guesswork: “This one’s a Jew.”

The next year, 1964, I had to pass through Dallas airport — not the town, just the airport. Paranoia is not my thing, but I felt damned uneasy, I tell you. I’d been an Adlai Stevenson idolizer, not a Kennedy idolizer, but back in 1960, just after J.F.K. won the election over Nixon, I wrote a piece that saw in the new young president some aspects of Shakespeare’s (and Olivier’s) Henry V. I think what had led me to write it was that moment in the campaign when Kennedy, perched on the back of an open touring car, had had a glass thrown at him from somebody in a packed crowd, and had caught it and gallantly handed it back with a casual, “Here’s your glass.” Now there had been another huge crowd, and another open touring car . . .

And Morris the copyboy who had missed the AP’s five bells? Well, in 1964 the opening of the Robert Moses World Fair in Flushing Meadows was thrown into a couple of days of total chaos by C.O.R.E. demonstrations against certain discriminatory corporate constituents. Morris the copyboy, inspired no doubt by Che Guevara and Regis Dubray, went out and lay down in the middle of the elevated subway tracks to stop the trains leading to the fair grounds.

Al Davis refused to fire him. “I want to be able to point at him across the city room and say: ‘There’s our Ph.D.,’ “ said Spike.